The 2024 census recorded 3,458 people homeless in Vermont, a nearly 5% increase over the number tallied in January 2023

By Carly Berlin

Editor’s note: This story, by Report for America corps member Carly Berlin, was produced through a partnership between VTDigger and Vermont Public.

The number of unhoused Vermonters living without shelter jumped last year, while the overall number of people experiencing homelessness has continued to climb amid an acute housing shortage.

Those are the results of the 2024 point-in-time count, an annual, federally-mandated effort to tally every person experiencing homelessness on a single night each January.

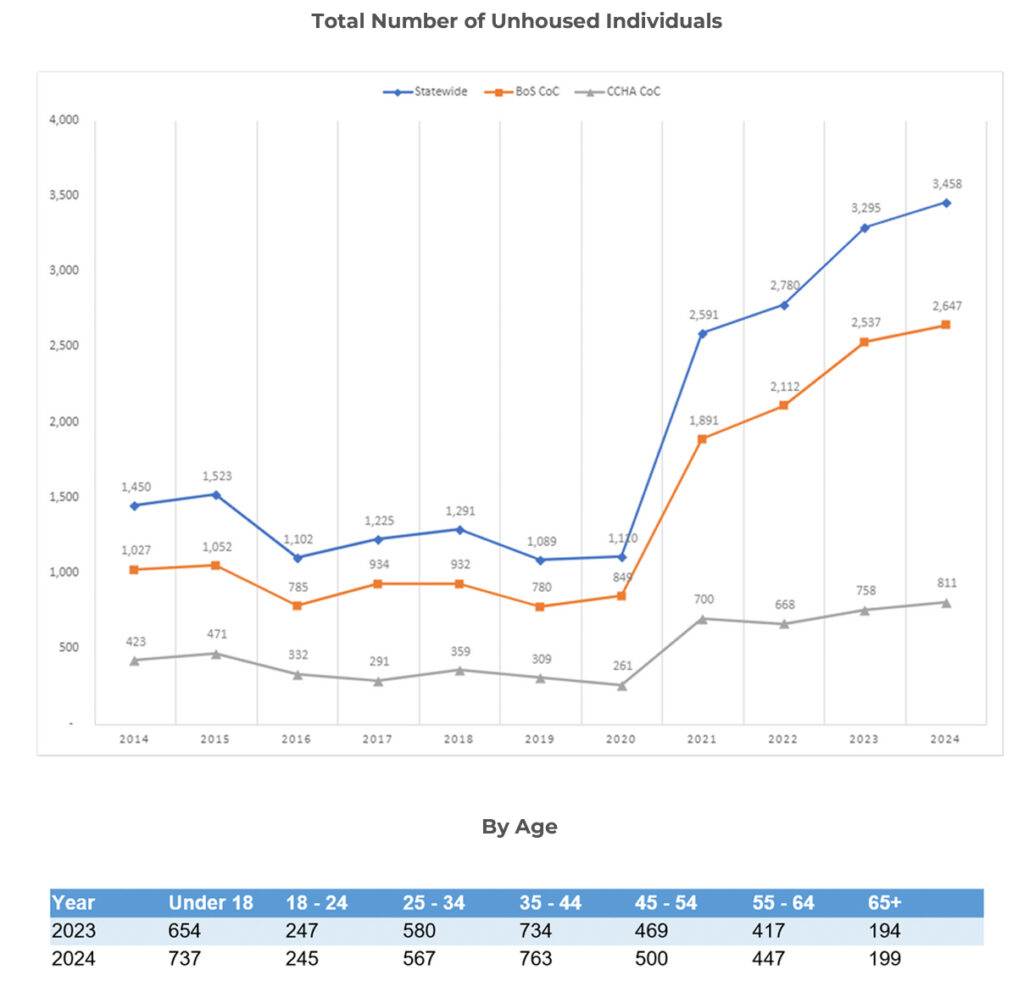

Statewide, this year’s census recorded 3,458 people experiencing homelessness, a nearly 5% increase over the number tallied in January 2023. That’s according to an analysis of this year’s data published Monday, June 17, by the Housing and Homelessness Alliance of Vermont and the two organizations that oversee the count, one based in Chittenden County and the other capturing the rest of the state.

Submitted

The number of unhoused individuals in Vermont has grown significantly over the past five years. The blue line shows the state total by year. The other two lines show Vermont’s two Continua of Care (CoC): the Balance of State CoC in orange and Chittenden County Homeless Alliance (Burlington/Chittenden County) in grey.

“Vermont continues to register record levels of homelessness,” Anne Sosin, a public health researcher at Dartmouth College who studies homelessness, said of the report’s findings. “This is unsurprising, given that homelessness is fundamentally a housing problem — and Vermont continues to face a large shortage of adequate, affordable housing.”

The year-over-year rise in homelessness recorded in the 2024 count is more modest than those of recent years.

It’s widely believed that the state’s expansion of the motel shelter program during the Covid-19 pandemic contributed to the massive increase in unhoused people counted in 2021: Because more people were in shelter, they were easier to count. To some, including Sosin, the 2021 tally gave the state a more accurate count of people experiencing homelessness than it had ever had.

But even as state leaders have scaled back the pandemic-era expansion of the motel program — and unhoused people have become more scattered — the state’s overall count of people experiencing homelessness has continued to tick up.

And as the state’s safety-net motel program has shrunk, more Vermonters appear to be unsheltered. Following a major round of motel program evictions last summer, January’s count registered a significant rise in the number of Vermonters living without shelter. The count captured 166 unsheltered people, which the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development defines as having a “primary nighttime location” like a vehicle or the streets. That’s up from 137 people in January 2023.

“To see that increase in that particular moment in time really speaks to the inadequacy of our shelter capacity in the state — in the depths of winter,” Sosin said, noting that statewide shelter capacity is typically at its largest during the coldest months of the year.

The report’s authors note that the count’s findings are almost certainly an undercount. Accurately counting people who are unsheltered is notoriously difficult. In a rural state like Vermont, service providers often lack the resources to fan out to remote corners where people might be staying, and the count only registers people who engaged with outreach workers conducting the January tally.

During this year’s tally, for example, the count registered 87 people experiencing unsheltered homelessness in Chittenden County. But that same month, at day shelters in the county, 182 people self-reported that they lacked shelter, according to the report.

The challenges inherent to counting unsheltered people could also muddy the count’s overall findings, Sosin said.

“As our ability to count people gets increasingly constrained, we will likely miss more people over time, even as the crisis of homelessness continues to grow,” Sosin said. “I don’t see the decrease in the number of people newly entering into homelessness as a reflection of a change in the situation as much as a reflection of the limits of our ability to count them.”

The definition of homelessness used for the count is also fairly narrow, Sosin noted, excluding people staying with relatives or sleeping on someone’s couch.

Though far from comprehensive, the count still provides insight into who is experiencing homelessness in Vermont.

This year’s count registered a stark racial disparity in Vermont’s unhoused population, one that has been persistent in recent years. While Black people make up 1.4% of Vermont’s total population, over 8% of people who are unhoused are Black.

The number of unhoused families with children dropped slightly last year, which Sosin said likely reflects greater investment and attention to that group. Even as the count captured fewer families, though, it clocked a major uptick in the number of young people experiencing homelessness: 737 people under the age of 18 were found to be homeless at the time of the count, up from 654 last year. That’s the largest jump in any age category tallied.

In addition to an affordable housing shortage, the report’s authors point to other factors driving the state’s housing and homelessness crisis, including rising housing costs and “a failure to provide adequate mental health and substance use services,” among others. And, with the state’s shelter capacity already strained, they note that upcoming limits to the state’s motel program, and an expected drop in housing stabilization funds, could exacerbate Vermont’s homelessness crisis this year.

The annual point-in-time count is used by state and federal officials to guide policy and funding decisions. While far from perfect, it offers some of the best comparative figures on the state of homelessness nationwide, and has formed the basis for federal reports showing that Vermont’s rates of homelessness are the second highest in the country.

Statewide summary:

(population 647,064)

3,458 – Number of unhoused people, representing an over 300% increase over pre-Covid levels (1,110 unhoused people in 2020).

166 – Number of people did not have access to emergency shelter, representing an over 21% increase over 2023 (137 unsheltered people in 2023).

309 – Number of unhoused people who were fleeing domestic or sexual violence.

855 – Number of unhoused people who had a serious mental illness.

568 – Number of unhoused people with a long-term physical disability.

254 – Number of unhoused people with a developmental disability.

107 – Number of unhoused people who were veterans.

737 – Number of unhoused people who were children.

199 – Number of unhoused people who were over 65 years old and 646 unhoused people who were 55 years old or older.

5.6 times – Number of times more likely Black Vermonters are unhoused compared with white Vermonters.

35% were unhoused for more than one year

72% were unhoused for more than 90 days.

Rutland County

(population 60,366)

682 – Number of unhoused residents

163 – Number of unhoused children

118 – Number of unhoused residents over 55 years old

14 – Number of veterans

39 – Number of people fleeing domestic or sexual violence

4.92 times – Number of times more likely that Black residents are unhoused compared with white residents

Length of being unhoused:

159 – Less than one month

16 – One to three months

254 – Three months to one year

245 – One year or more

Number of unhoused residents with a:

70 – Physical disability (long-term)

28 – Developmental disability

109 – Mental health (severe and persistent)

35 – Chronic substance abuse (alcohol and/or drug)

50 – Other chronic health conditions (long-term)

Windsor County

(population 58,142)

173 – Number of unhoused residents

41 – Number of unhoused children

36 – Number of unhoused residents over 55 years old

6 – Number of veterans

7 – Number of people fleeing domestic or sexual violence

3.6 times – Number of times more likely that Black residents are unhoused compared with white residents

Length of being unhoused:

21 – Less than one month

15 – One to three months

67 – Three months to one year

70 – One year or more

Number of unhoused residents with a:

21 – Physical Disability (Long-Term)

10 – Developmental Disability

29 – Mental Health (Severe and Persistent)

5 – Chronic Substance Abuse (Alcohol and/or Drug)

14 – Other Chronic Health Conditions (Long-Term)