By Anne Wallace Allen/VTDigger

Veterinarian Susan Johnson used to work with 15 large alpaca farms. Now Vermont’s down to just a few. But an Ascutney farm, Cas-Cad-Nac, is doing the alpaca business in a big way. It has 250 super-premium alpacas, half-ownership in a fiber mill, and a mail-order alpaca meat business.

And this autumn, it produced the world’s first alpaca baby from a frozen embryo.

Alpaca farming is an unusual business that isn’t generally recognized as the agricultural pursuit that it is, said Jen Lutz, who started Cas-Cad-Nac with her husband on their 600 acres more than 20 years ago.

“We’ve fought to get them defined as livestock. They’re a fiber-bearing animal, and it’s legitimate,” said Lutz. “But we’re alpacas, so we’re under ‘crazy.’”

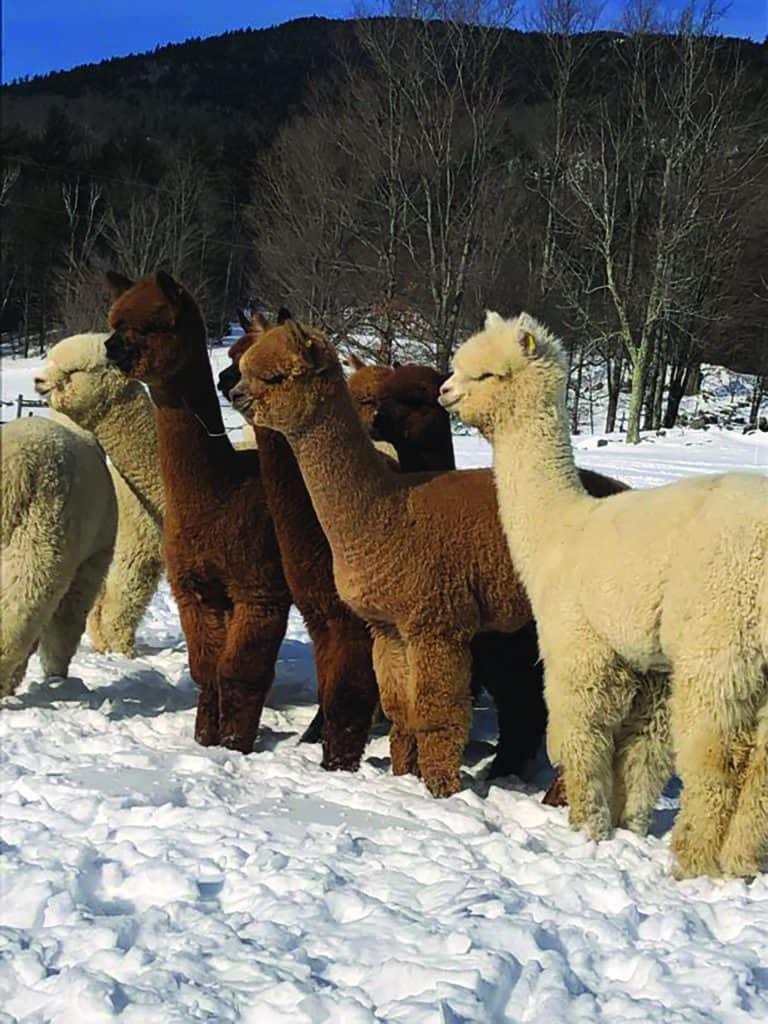

Alpacas, members of the camelid family, generally weigh between 100 and 200 pounds. They come from South America, where they have been bred as livestock for generations. They eat hay and produce a thick, soft coat that is spun into yarn.

Alpacas enjoyed a brief burst of popularity in the U.S. in the 1990s and early 2000s, with Americans importing the gentle, stiff-necked animals to keep as pets in the pasture or as an investment for their fiber-bearing potential. But the market for alpacas collapsed, and now the animals, which feel like ultra-plush teddy bears, are easy to find for free on sites like Craigslist or at animal rescues.

Cas-Cad-Nac rode the wave of the alpaca’s popularity, investing in high-end breeding stock in the 1990s. The farm won its first blue ribbon at the Big E in Springfield, Massachusetts, and now sells its registered alpacas for as much as $20,000 to buyers around the country. It also charges stud fees of up to $4,000 to alpaca owners who bring their females to the farm. For years, they exported animals to Europe until trade regulations made it impractical. Last year, the farm won a national championship with one of its alpacas at an Alpaca Owners Association show in Indiana.

Cas-Cad-Nac is known nationally among alpaca farmers for the exceptional animals it produces and shows, said Jeff Williamson, who owns Liberty Alpacas in Battleground, Washington. Williamson, vice president of the national Alpaca Owners Association, competes against Cas-Cad-Nac at shows from time to time.

“They’re one of the top breeders in the country,” he said.

Like many industries, the alpaca business has become concentrated among several large producers, said Lutz.

“We end up going to the bigger shows on the national level,” she said.

Johnson, who now works mainly as a small animal veterinarian, said the alpaca business hasn’t been fully recognized by the veterinary profession and regulators, and lacks effective guidelines regarding medication and meat sales.

“The whole industry is kind of a wonky thing,” she said. “It’s different from any other industry that we deal with.”

Bred for fiber

Cas-Cad-Nac started Vermont Fiber Mill and Studio in Brandon, 55 miles to the north, with Ed and Deb Bratton in 2011 to create a place to process the alpaca fiber. Ed and Deb Bratton had worked in corporate IT and project management in Missouri before moving to Vermont in 2000.

The two had never been around an alpaca when they built their 100-acre farm in Brandon. Now they have 25 of the animals, and they work full-time milling wool, mohair, and alpaca for customers around the country.

“Deb realized that alpacas were pretty gentle; she wasn’t intimidated by them at all,” said Ed Bratton.

“If an alpaca kicks you, it’s not like a horse or a cow,” Bratton said. “It doesn’t break anything; it just startles you.”

The company washes the wool and fiber in rented space at the former Brandon Training School, and mills it on several machines at the farm in Brandon.

A sideline in alpaca meat

Cas-Cad-Nac’s breeding non-performers end up in meat form, frozen solid in cryovac packaging, to be shipped around the country in coolers on dry ice.

“Alpacas in Peru have been eaten for 60, 100 years; it’s a wonderful meat,” said Johnson, who has lectured internationally on the topic of alpaca meat. “If they’re not pregnant at lunch, they eat them for dinner. It’s not a big deal.”

Lutz is more reticent about the meat side of the business, fearing it will upset people.

“Alpacas are cute and cuddly, and sheep are cute and cuddly, but for some reason there is a disconnect between the two,” said Lutz.

Cas-Cad-Nac also sells whole alpaca pelts for $400. Lutz noted there are others who sell alpaca meat in Vermont, including Pioneer Food Truck and Catering Company, based in Colchester. The company sold alpaca burgers last fall for the first time, and it’s now a permanent menu item, said Jean-Luc Matecat, who owns the seasonal business with his wife, Lindsay.

“It’s a way for us to use the whole animal,” Lutz said.

Groundbreaking research

It’s easier to talk about the embryo business, which Lutz worked on with Iowa State University researcher Curt Youngs. The farm’s first baby alpaca developed from a frozen embryo was born in November 2019 on the farm and received the other-worldly name of CCN Exuberant Frost Blossom-ET.

While other livestock breeders had used frozen and thawed embryos for years, it hadn’t yet happened with an alpaca cria or baby, said Youngs. Such embryo transfers are routine with cows and other livestock; freezing the embryo greatly extends the time it can be transported and stored.

For the project — more than 10 years in the making — Youngs visited twice to work with Lutz. The two presented their work in January at the annual conference of the International Embryo Technology Society in New York City. Youngs credits Lutz for having the brains, dedication and perfectionism needed to carry out such work on the farm — including her study of similar research underway in the United Arab Emirates on an alpaca relative, the camel.

“She’s not the typical farmer, from the standpoint that she actually reads scientific journal articles, she’s willing to take some risks and try some new things, and now she’s done something that no one else has done,” said Youngs.

‘A very different critter’

Cas-Cad-Nac isn’t the only outfit producing prize-winning alpacas in Vermont, but it’s one of only a few. Williamson estimated there are 250,000 U.S. alpacas registered with the owners’ association.

Alpaca keepers like to note that alpacas aren’t at all like other livestock. Youngs said that when it comes to reproductive physiology, “the alpaca is a very different critter.”

Johnson described them as “pseudo-ruminants” that chew a cud but don’t have the same digestive system as other cud-chewers.

“They’re a bit like a horse, a little bit like a sheep, a little bit like a goat and a little bit like a cow,” Johnson said. “The joke in the industry is Dr. Seuss built an alpaca with leftover body parts.”

They require better nutrition — high-quality leafy green hay — than sheep and goats, and have a longer gestation — 11 months — than those animals, which give birth after 5 months, Johnson said.

But raising alpaca is similar to mainstream agriculture in this respect: it’s getting more difficult all the time, said Lutz. She said the decline of the alpaca business started in 2008 as the economy went into recession.

“Prior to that, animals were selling for crazy money,” she said. “And then you could definitely see auction prices were starting to decrease, and you started hearing about backyard animals weren’t being taken care of. Animals that were being neglected for the first time.”

Cas-Cad-Nac is seeing some of the consequences that other farms are, as operations succumb to financial pressures. About 50 dairy farms closed last year, according to the Vermont Agency of Agriculture, Food and Markets.

Cas-Cad-Nac’s closest Bobcat dealer is 75 miles north in Berlin.

“The equipment dealers are getting farther and farther away from us,” she said. “The smaller dealers don’t have enough people around them so they shut down.”