By Karen D. Lorentz

Having observed the development of skiing in Sweden, Vermont State Forester Perry Merrill envisioned similar recreational and economic possibilities for skiing in Vermont.

During 37 years on the job, he oversaw the purchase of 170,000 acres of forestland in 27 state forests and 32 state parks. He negotiated many long-term leases with ski areas — Mount Mansfield, Burke Mountain, Jay Peak, Smuggler’s Notch, Okemo, and Killington, to name the big areas while there were smaller rope tow areas like the one at Shrewsbury Peak, which operated on state lands leased to a Rutland group in 1935.

The late Vermont Senator George Aiken wrote of Merrill, “It was in no small way due to his aiding and abetting, cajoling and urging, that Vermont is now noted for its excellent ski areas.”

One of Merrill’s reasons for leasing state land to ski operators was to provide income for Vermont’s state parks. It was the lease payments and revenues from food and retail sales in the lodges on state land that provided a substantial income for his state parks operating budget. That is why fees for day and overnight camping uses could be so nominal as to be affordable to virtually everyone.

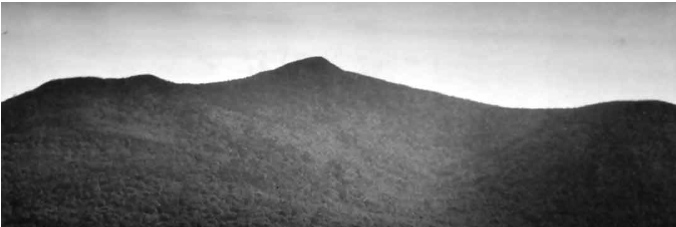

A view of the mountain Merrill wanted to develop for skiing: Skye Peak (left), Killington Peak (center), and Snowdon (right).

Finding someone for Killington

In 1954, the father of Vermont’s state parks and alpine ski areas finally met with success in attracting someone to develop Killington when Preston Leete Smith, 24, visited him to see about buying Ascutney Ski Area, which was for sale.

Although Merrill wasn’t talking to a group of businessmen with the financial wherewithal or practical experience to develop a ski area, he had found someone who shared his appreciation for the sport of skiing.

He told Smith about Vermont’s second-highest mountain, saying, “Come back and see me after you’ve seen Killington.”

A tall, almost shy young man, Preston “Pres” Leete Smith had a far different background from most ski area entrepreneurs of the time. He had not grown up with family working in the ski industry, his parents weren’t skiers, and he hadn’t been part of the 10th Mountain Division, which spawned many a ski area founder.

Smith’s route was roundabout and founded not on being in a position to develop a ski area but on a love for the sport. Hard work, determination, and a love of what he was doing were the elements that made his entrepreneurship possible. His upbringing fostered this possibility.

From cows to skiing

Preston Leete Smith was born to Bernice Leete Smith and Robert Avery Smith in New York on February 3, 1930.

“I happened to be born in New York City because my father aspired to be in show business in his early years,” he said [in a 1988 interview] of the nine months of his life not spent as a New Englander. The elder Smith was a baritone singer performing on Broadway, but since it was the Depression Era, it was a short stint, and the family returned to the Leete family homestead in Guilford, Connecticut.

Pres Smith’s early boyhood was spent on Leete’s Island, a section of Guilford named for his ancestor William Leete, the first governor of the New Haven Colony. (Later, when the New Haven and Hartford colonies merged into the State of Connecticut, William Leete served as governor of Connecticut.) The family lived in the 16-room home of his maternal grandfather, Calvin M. Leete. The house was located on the same plot of land that had been in the family since 1670. The adjacent acreage was owned by cousins who operated a full-time dairy farm with 30 head of cattle. “I grew up farming from the time I was old enough to herd cows,” Smith related.

A career change by his father brought about a move, and his parents established a business in West Hartford Connecticut. After attending Plant Junior High, Smith went to Oakwood, a prep school in Poughkeepsie, New York. He returned summers to work on the farm. The experience was not without impact — his younger twin brothers Avery and Alcott became veterinarians, and Smith studied agriculture in college.

However, Smith recalled having had more aptitude for engineering in high school. “I really liked and excelled in math and science. But my folks were not oriented to that sort of thing. They were into art — my father’s success was in early American antiques, American primitive art, and antique oriental rugs.

“He and my mother were not into the same interests that I was. They were not into sports, and I was always involved in sports — football, basketball, baseball, and track. Ice skating was my real love and an aspiration aside from aeronautical engineering. I loved planes…used to draw planes all the time. I remember being particularly fascinated by the Flying Tigers. My tests and grades in school would have indicated that I should pursue engineering, but no one encouraged me to do that.”

With his parents having become Quakers and joining the Friends’ Society in West Hartford, Smith attended Earlham College, a Quaker liberal arts school in Indiana. There, he majored in agricultural science, taking natural and physical science courses, including forestry, soil science, biology, chemistry, and physics. He graduated with a science degree in 1952.

After college, Smith had a variety of jobs. He tried to get a position in the insurance industry but was “turned down. I guess they didn’t think I’d make a good salesman.” As a conscientious objector, he worked for Goodwill Industries instead of military service. He also worked at a silk screen shop in Guilford and became shop manager.

It was during this time of first employment that Smith got into skiing seriously.

He had taken backyard runs as a youngster, thanks to his Uncle Preston Leete, who was interested in the sport. During his teenage years, a family friend took Smith to Mohawk Mountain, a small area in Cornwall, Connecticut. It was “the first bona fide ski area” he visited. But he couldn’t afford skiing during his college vacations, so after college, he “really learned to ski,” and the memorable trips to Vermont began.

Smith recalled “hooking up with the New Haven and Waterbury ski clubs, and when they didn’t offer a trip, I drove myself.” He met Walter R. Schoenknecht, president of the New Haven club, but although Schoenknecht was promoting Mount Snow, Smith couldn’t afford to buy stock. Schoenknecht, the legendary ski area visionary and entrepreneur, also ran Mohawk, a ski area he founded in 1947, and Smith became a ski patrolman there, which helped to make his skiing more affordable.

Passion

Commenting on his desire to ski, Smith had said: “I had a terrible time skiing every weekend because I didn’t earn very much money. I used to drive twelve hours in a snowstorm in an old convertible, wearing a motheaten raccoon coat and eating peanut butter and crackers just to get to Stowe. I was always looking for deals on skis and forever putting edges on them; they were the metal screw-on sections in those days. You were forever damaging them, and it just made it that much harder to afford the sport.”

On one trip to Pico, Smith remembers “barreling down B Slope in the rain and jumping as far as I could off the big boulder toward the bottom of the slope. I landed in soft snow, sunk in about two feet, and stopped dead because my skis refused to slide. I egg beatered down the hill, breaking them into splinters.” The bad fall didn’t bother him. The expense of replacing the skis was the greater problem!

On occasion, he couldn’t afford the dollar fifty to sleep at Scotty’s Bunkhouse in Stowe, so he slept in his sleeping bag in the car in zero-degree weather.

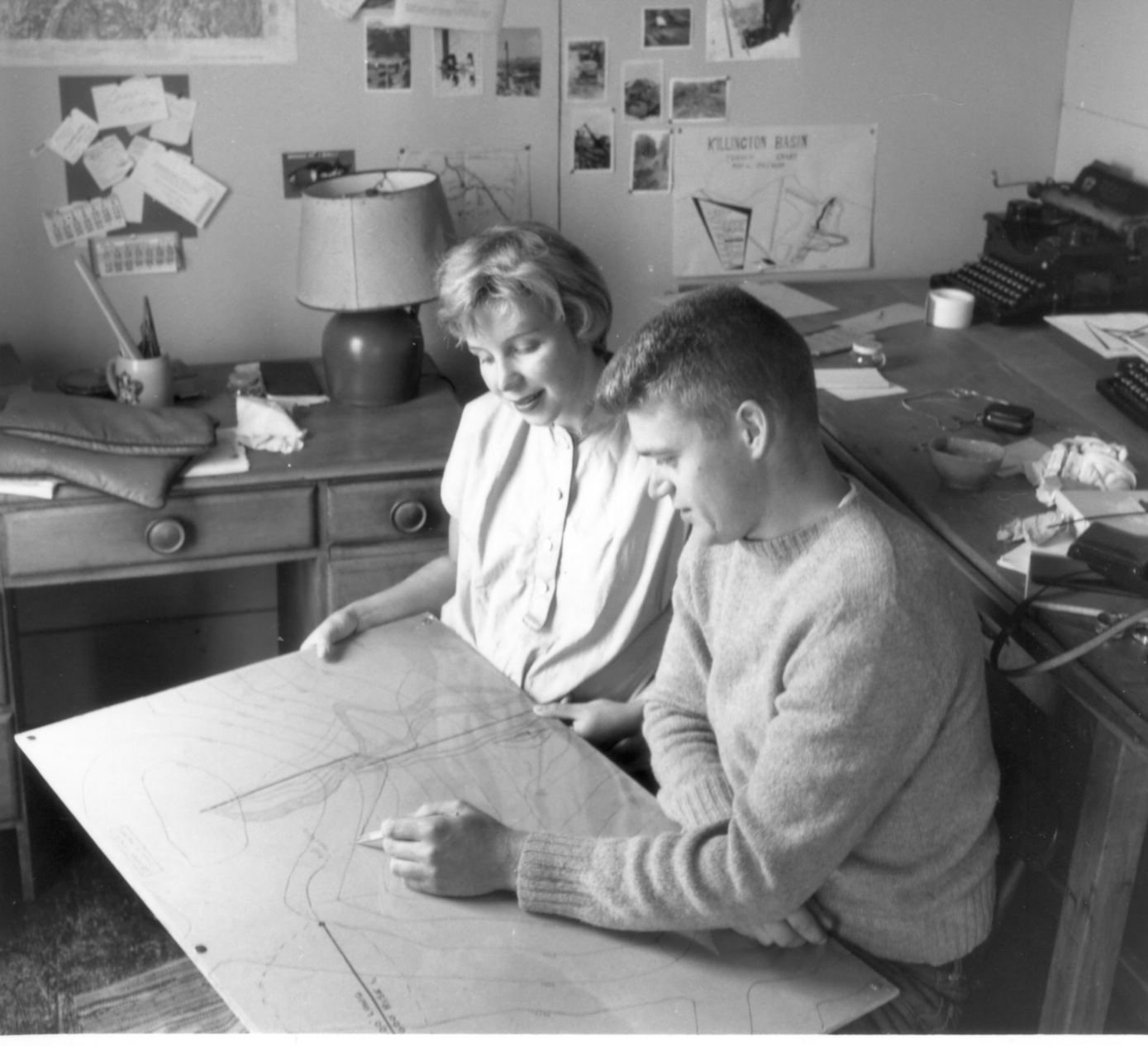

In 1954 Smith met Susanne Hahn and, having become engaged, began to think seriously about his career.

Sue Smith recalled, “The appeal of skiing and the lure of the mountains caused us to consider Vermont.” With Mount Snow recently launched, the couple thought of purchasing property and building a ski lodge there, but after several trips to the area, it soon became apparent to them that financing a lodge was out of the question.

“I had no money and few people would be interested in financing a ski lodge. But there were a lot of people interested in a ski area — I thought the financial support would be there,” Smith recalled.

Next week, in Part 3, we’ll meet the people who strengthened Smith’s determination to operate a ski area.