By Karen D. Lorentz

Editors Note: This is Part 3 of a three-part series that explores how innovations at Okemo and Killington enabled them to become successful and popular ski resorts that also contributed to the growth of the ski industry in Vermont and the East.

Killington’s pioneering approach

The cover of Killington Resort’s first winter brochure, then called Killington Basin in Sherburne.

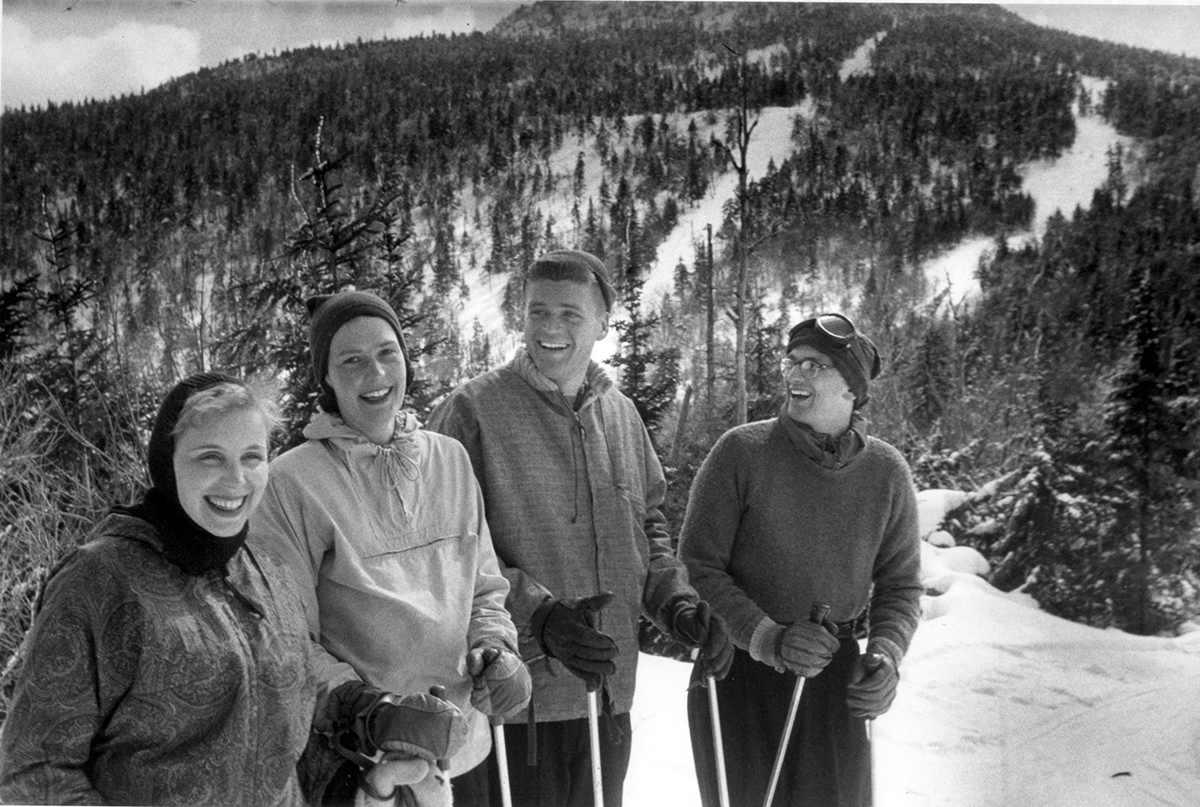

Killington co-founder Preston Leete Smith had been bit by the ski bug and after experiencing long waits at Mount Mansfield’s old single chair thought that “there had to be a better way” to operate a ski area.

Wanting to get into the ski business, Smith went to see Vermont State Forester Perry Merrill about Mt. Ascutney in 1954. Merrill, who had been trying to interest someone in Killington since acquiring the peak (a gift of 324 acres) in 1938 and purchasing the surrounding 2,776 acres in 1945, told him to check out Killington.

After studying the mountain, Smith went back to Merrill and learned the state would lease it to him and build an access road, a parking lot, and ski shelter.

Raising the money to build the lifts and trails proved problematic until Smith met avid skier and Hartford, Connecticut, businessman Joseph D. Sargent. Sargent, who saw Smith’s plans for a three-mountain complex with European cabin lift as grandiose and beyond his means, thought the project feasible if a company with stockholders was formed and if the plans were scaled down for the first year.

Sensing a kindred spirit who also wanted the ski area to be profitably run, Sargent invested and gave Smith the names of potential investors. One was Hartford businessman Walter N. Morrison, who like Sargent would spend weekends helping to build the ski area. The three men functioned well together as a decision-making team and as the executive committee were largely responsible for Killington’s success and business approach to ski area operations.

Due to various hassles — getting the 5-mile access road built and obtaining the lease —Killington didn’t open until Dec. 13, 1958.

With the same tenacity he approached every challenge to ski operations, Smith persevered. Not only did he raise $127,500 through the sale of stock (at $250 a share) to open Killington, he eventually fulfilled the goals of becoming a world-class ski area and taking the company public.

Innovation rules

With Smith’s drive to create a better ski experience, Killington became a pioneer in ski-area innovations. The area developed the ticket wicket; opened earlier and closed later, extending its ski season to six months; changed the snow reporting format to Smith’s more objective factual report — inches of new snow, base depths, terms like powder, frozen granular — that was then adopted by the Vermont Ski Areas Operators Association and eventually used nationwide; debuted a try-before-you-buy concept in 1967-68 with free skiing for the first hour of lift operations so skiers could sample the snow before buying a lift-ticket; pushed lift manufacturers to produce higher capacity lifts; and took grooming and snowmaking technology to new heights as well.

In the process, Killington earned a reputation for offering the most terrain and the longest ski season in the East (and some years in the U.S.), dependable snow conditions, and an avant garde ski school that revolutionized ski instruction in the 1960s and 1970s.

Snowshed lift and trails

A willingness to experiment and find a better way to meet skier needs was set in motion by Smith when he designed and built the Snowshed beginner area in 1961. The lift manufacturer actually believed Killington had made a mistake in its specs because they had never received an order for a chairlift to be built on such a flat hill.

Killington’s former General Manager Paul Bousquet said, “This idea to cater to beginners with what was at the time considered to be very flat terrain was unheard of in the ski industry and was tremendously risky. It was scary because we didn’t know it would fly.”

But seeing the rising popularity of skiing and need to teach beginners, Smith was willing to invest in a new concept and the three-quarter-milelong Snowshed became a popular learning hill that was eventually expanded many times.

Snowmaking, grooming dedication

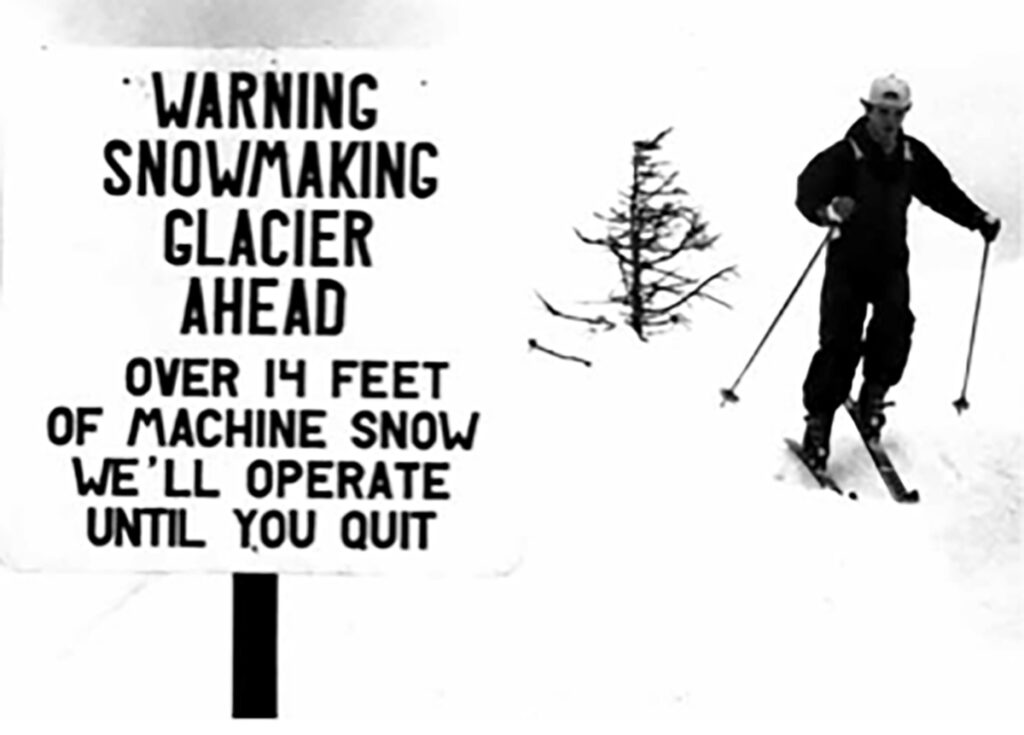

A sign celebrates Killington’s snowmaking prowess.

Another phenomenon where R&D was to have lasting effects—not only at Killington but on the ski business—was snowmaking. Although Killington wasn’t the first to install snowmaking, it was the first area to pioneer improvements and implement its own systems.

This stemmed from the disastrous installation of snowmaking on Snowshed in 1963, when the company responsible for the system misjudged the pressure that built up in the aluminum pipe and it blew up. Smith dismissed the company, and thereafter Killington used its own engineers to oversee snowmaking, design its own guns and systems, and adopt the use of computers.

In 1971, snowmaking was installed top-to-bottom on Snowdon Mountain and expanded to Killington Peak in 1972 and by 1974 its 1,642-vertical-foot drop was covered top-to-bottom with snowmaking on the challenging Cascade trail.

In the 1974 Annual Report, Smith announced; “In the future we believe that if ski areas are to be viable, complete snowmaking facilities will be necessary, not only to forestall the consequences of snow drought, but also to insure quality skiing conditions throughout the season.”

He noted that due to the wear and tear skiers were exerting on the slopes, “snowmaking is here to stay. Henceforth, ski operators will depend solely on machine-made snow to ensure the quality of their skiing experience.”

But with the high cost of snowmaking systems and the 1970s’ rising liability insurance rates and escalating energy costs, it would be the mid-to-late 1980s before most Vermont (and other northeastern) ski areas committed to snow being the product that they sell.

Killington also sold its patented guns and systems to other ski areas, seeking not only business for themselves but to help the industry along.

Smith later saw that the technologies of snowmaking and grooming — notably the development and refinement of Kassbohrer’s Pisten Bully 200W winch cat, which largely occurred at Killington in 1984-1986 — would make it possible to offer lift-served skiing on Skye Peak (previously deemed too wind-and-weather susceptible to be skied) and Bear Mountain, once thought too steep to hold snow. Thus, Outer Limits became the steepest, longest bump run in the East, and Superstar, another steep, proved to hold snow into May thanks to generous snowmaking.

Ski instruction spurs growth

Smith was the only ski area operator to accept Ski magazine’s invitation to see if a short ski could serve as a learning tool to improve and accelerate the learning process. Again, there were many who were skeptical and some scoffed at the notion of using “baby skis.” But Ski School Director Karl Pfeiffer saw the potential in preliminary tests in 1964 and worked in conjunction with Ski to develop the Graduated Length Method (GLM), which involved learning on a 39-inch ski for two days, 5-footers for two days, and skiing on a regular-length ski on the fifth day of a GLM Ski Week.

With the promise of parallel skiing in five days, Killington inaugurated a Uni-Ski Vacation for the 1966-67 season. It included a 5-day learn-to-ski package with GLM equipment and daily 2-hour lesson, lift ticket, après-ski social program, food, and lodging at a total cost of $97 ($944 in today’s dollars). The Uni-Ski Week made it easier for the new skier to take up the sport, and Killington became the first ski area in the country to market a comprehensive ski package (offering both traditional and GLM learning options).

With snowguns making it possible to guarantee snow, Killington saw its ski week attendance skyrocket. The area was soon processing 800 to 900 beginner ski-weekers on a Sunday evening and saw that climb to “2,000 and even more at peak times well into the mid-1970s. Weekend ski school added even more,” noted Leo Denis, former ski school director and vice president-skiing.

“It was the phenomenal midweek revenues from ski school that enabled Killington to grow, expand, and become so successful,” Denis said, adding that as a result Killington became one of the first areas in the U.S. to include the ski school director as part of the management team.

Gondola innovations

The original Killington gondola was considered unbuildable by most lift engineers. But Carlevaro and Savio thought that Smith’s requirements for a 4-passenger, higher capacity, 3.5-mile lift with automatic entry and exit from both sides of the cabin would be doable if done in three sections. The prototype Killington Gondola became the longest lift in the world and operated in three stages, running either independently or as one continuous lift and had a capacity of 1,500 rides per hour, about 50% greater than any gondola at the time.

The $875,000 lift ended up costing $3.5 million ($30 million in today’s dollars) and took three years to build instead of one. With parts not working and transfer systems under-designed for the heavier four-passenger cabins (hoses popped, hydraulics failed, and cabins had to be hand pushed through the terminals), Killington redesigned and rebuilt the system with its own engineers. In 1994 the two-stage, 2.5-mile, eight-passenger Skyeship, which terminates at Skye Peak, replaced the prototype gondola with the world’s first heated gondola cabins.

Computers, marketing, profitability

Killington Basin’s first-brochure-shows-summer-was-in-the-plans-for-a-three-mountain-ski-area.

Killington’s business approach saw an office manager and a systems analyst hired in 1960. It also included the use of computers in the 1960s and specially designed cash registers for automatic ticket printing and control. In the 1970s, Killington developed computer programming for ski area management, and, in 1984, a management information services department was formed. It utilized sophisticated computers and fostered the efficient use of computers in other departments.

This business approach to ski operations also included the 1961 addition of a news and public relations department which eventually became part of a professional marketing department that sought to attract people from all walks of life. Killington established a market research program that could track how other areas were doing; studied skiers through surveys and exit polls; and pioneered a variety of advertising and promotional innovations like the insertion of trail maps in ski publications and the development of the comprehensive ski-week vacation package.

Through these innovations (among others) and a business approach focused on assured consistent profitability, Killington contributed to the wellbeing of the skier and ski industry and became a very successful ski area (No. 1 in the East for skier visits). That led to fulfilling an original ambition to go public and to own and operate other areas, which it did as S-K-I Ltd., before being sold in 1996.

Interestingly, three owners later, Killington and sister Pico Mountain are now privately owned by another group of enthusiastic skiers who are honoring the resorts’ accomplishments by keeping its leaders in place and continuing to work co-operatively with Great Gulf toward the goal of developing a world-class resort village.

Karen D. Lorentz is author of books on Killington and Okemo. She is working on a history of Vermont skiing and would like to hear ([email protected]) from skiers with roots in early Vermont skiing.