By Maggie Cassidy/VTDigger

Meteorologists at the National Weather Service’s Burlington office pivoted among computer screens, each displaying a colorful digital smorgasbord of data. Interspersed with spreadsheets, line charts and big blocks of text, eight maps of New York and New England were overlaid with a variety of wavy lines, and numbers — lots of numbers.

Indecipherable to most people, the toolset helps meteorologists like Maureen Hastings decide whether to issue winter weather advisories — or flood watches, like after this past week’s winter thaw.

Hastings’ determinations are used by ski area operators, road crews, superintendents, public safety officials, pilots, journalists and anyone impacted by the weather, which most days is most people. These judgment calls are the kind that she and her colleagues make on a routine basis, beamed out to the world from their second-story office at the Patrick Leahy Burlington International Airport.

“It’s a lot of working toward helping people make decisions and then act on those decisions,” Hastings, 45, said in a prior interview.

Staffed 24/7 by 13 meteorologists in rotating shifts, as well as three scientist-managers, the weather service’s Burlington office occupies an unusual space in Vermont’s public eye. In some ways, its forecasters are semi-public figures akin to spokesperson for the skies, their names peppering news stories before, during and after extreme weather events. Anyone can phone their office to seek their counsel, and the line is used by reporters, random residents and even a few regular callers.

But the meteorologists also spend much of their work time toiling unseen in the depths of dense scientific calculations. Their closest partners are often behind-the-scenes decision-makers at official entities such as Vermont Emergency Management, and during weather-related catastrophes like floods and storms, they provide one-on-one guidance to state government’s upper echelons.

Several were drawn to their careers following natural disasters in their youth. For Hastings, it was a tornado that tore through her Kansas hometown when she was in third grade.

It’s not unusual, they said, to meet people who misunderstand what they do. For one thing, they don’t work in Television.

“I do notice that when people ask me what I do, and I tell them I’m a meteorologist, they immediately want to know, like, what channel or am I on the radio. And this kind of operational forecaster job kind of runs under the radar,” said meteorologist Jessica Storm, 26. (No, she doesn’t find it annoying when people note her surname. And, yes, she likes weather puns.)

Lead meteorologist Robert Haynes, 32, who chose The Weather Channel over cartoons as a kid, said he’s also often erroneously associated with its programming. This job, though, is one of civil service.

“When we kind of tell people, like, no, we’re actually a part of the federal government, that can sometimes throw people for a loop,” he said.

By Glenn Russell/VTDigger

Tyler Danzig at the National Weather Service Office at Leahy Burlington International Airport in South Burlington monitored several screens of data as heavy rain moved into the area just before the new year. Many people and businesses (including ski resorts) rely heavily on weather forecasting, but the dynamics of how those calculations turn into predictions and then how those probabilities are communicated, is not well understood, meteorologists say.

Forecasting: A team sport

The crew in South Burlington comprises one of 122 forecast offices for the National Weather Service, (NWS) itself one of six branches of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, (NOAA). Burlington’s coverage area includes part of upstate New York and all Vermont counties except Bennington and Windham. Those southernmost areas are covered by the office in Albany, New York, with which Burlington works closely, alongside other neighbor offices in Buffalo, New York, and Gray, Maine.

Conveying probability — without a crystal ball

Science Operations Officer Pete Banacos, 50, said much has changed in the 26 years he’s worked for the weather service, mostly in Burlington. As the computer monitors “get flatter and bigger,” he quipped, improved numerical models have allowed today’s forecasters to predict seven days out with the same level of accuracy that was constrained to four at the start of his career.

Such advancements empower forecasters to fine-tune other elements of the job, like the messaging. The primary approach they’re working on these days, the meteorologists said, is “probabilistic messaging.” That means explaining the probability of various weather scenarios — usually using percentages — so that Vermonters can understand the chance of best-case, worst-case and most likely outcomes.

State and local emergency officials may be most interested in the worst cases, even when unlikely, so they can get prepared, Banacos said. Meanwhile, the average Vermonter might need to know that an unlikely scenario is on the table, but they shouldn’t be surprised if it doesn’t come to pass.

An individual’s profession may also determine what they want to know about the likelihood of hitting certain thresholds, Banacos said, whether it’s the probability of surpassing a given wind speed, precipitation total or other metric.

“So we’re getting more into the probabilistic space where we say, what are the chances of, say, 4 inches of snow falling on a particular day?” Banacos said. “And maybe that’s a threshold that’s important to a snow plow driver — they’re going to go out for a 4-inch snowstorm. So they want to know, what’s the percent chance at their threshold of something happening?”

The approach represents a shift away from the hyper-specific forecasts of decades past, said Banacos, who sat in a conference room defined by another huge screen but also displays of antique tools like a wind anemometer and a barograph. He said “tiny little ranges” for predicted snow totals, like 1 to 3 inches here and 2 to 4 inches there, may have been unrealistic and given the public false impressions.

Meteorologists are working such probabilistic phrasing into conversations with journalists, public safety officials and other stakeholders who communicate with the public. For example, Haynes said, instead of saying “You’re going to get 6.7 inches of snow today,” the probabilistic version could sound something like this: “There’s a 50% chance that you’ll get more than 6 inches of snow, or … your high-end range that you could see and should prepare for (is) maybe 10 inches of snow.”

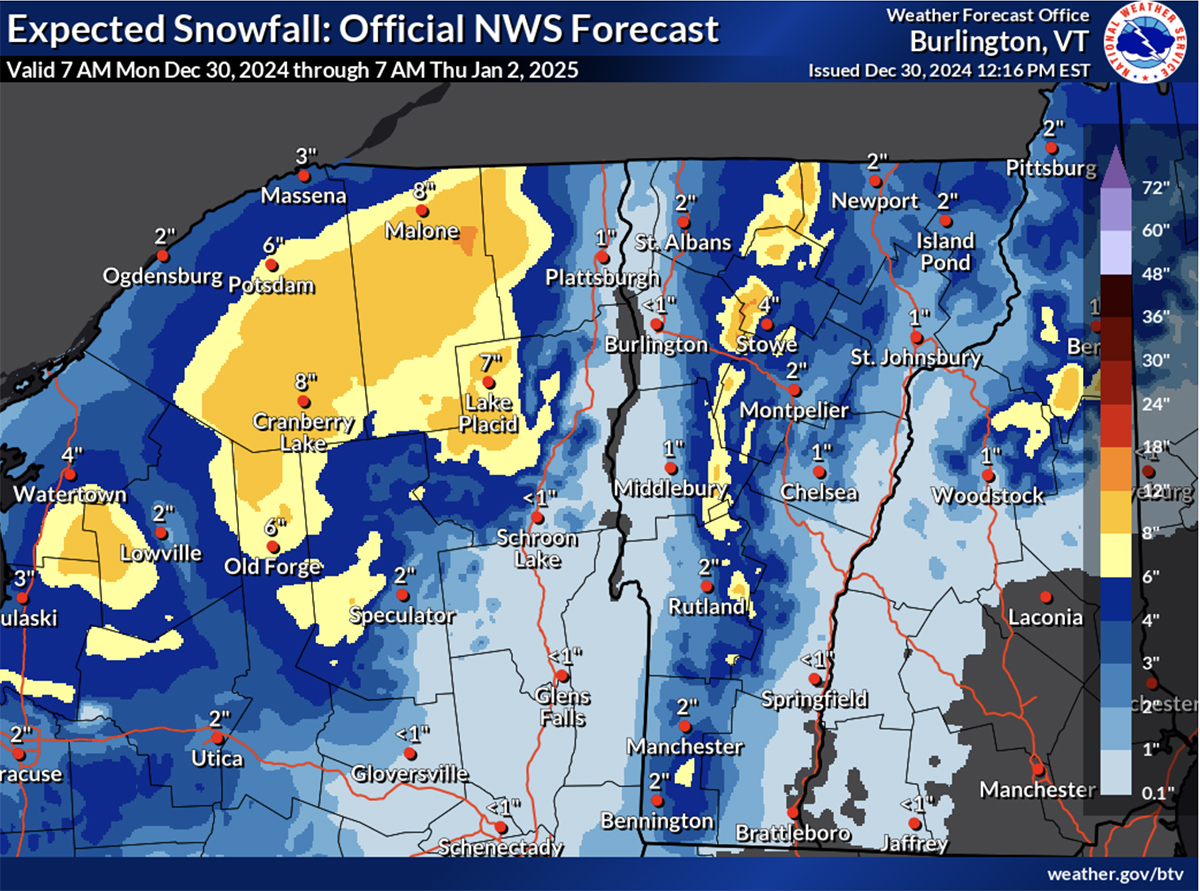

They’re also experimenting with new digital tools, such as the weather service’s “probabilistic snowfall products” on its website. Visitors might see a grid of regional maps, each representing a different snowfall total — one map for 6 or more inches, another for 8 or more inches, and so on — with different percentages of likelihood marked across the towns in each map.

The overall effort is a work in progress, Banacos acknowledged. It’s not always easy to convey nuanced statistical calculations to a population with a range of mathematical inclinations and competing demands on their attention. He’s sensed that some consumers expect near-perfect forecasting in the digital age, but that most recognize that scientists have yet to develop a “crystal ball.”

“As a result of such improvement [in forecasts], I think sometimes people expect that level of skill, like, every time,” Banacos said. “And so when those hiccups happen where we miss the mark completely, I think sometimes it does catch people by surprise. … But that’s where the probabilistic messaging can sort of help take the edge off.”

Snow declines, politics rise

In some ways, the pressures on the job are growing. There’s the looming politics of it all.

Though the weather service generally enjoys broad congressional support, its parent agency, NOAA, is among the agencies recommended for deep cuts in Project 2025, the ultra-conservative political plan associated with President-elect Donald Trump, a climate change denier. (There are no specific federal budget line items for individual forecast offices, Banacos said, but he calculated each American’s share of the National Weather Service’s most recent $1.3 billion appropriation at less than $4 for the year.)

There’s also the effects of climate change itself. The topic is generally outside of the weather service’s scope, except to the extent that the data it’s constantly collecting is analyzed by other scientists to show broader trends.

Nevertheless, Vermont’s day-to-day weather — the Burlington office’s purview — is impacted by climate change, and the effects of global warming make for trickier daily forecasting. Vermont weather is trending warmer, wetter and more extreme, according to the state’s lead meteorologists, with the state more often vacillating between droughts and floods.

Storm, who has worked in Burlington for two years, said some of her veteran colleagues remember days when the winter predictions were mostly snow, but she’s been forecasting plenty of rain and ice. She pointed to the increasing unpredictability of Vermont’s shoulder seasons and the difficult nature of “marginal temperature events,” in which minor temperature fluctuations can affect whether precipitation falls as rain, snow or ice, with outsize effects on the forecast.

Marginal temperatures were historically more typical in the mid-Atlantic region, Storm said, but are presenting more frequently in the Northeast. They contributed to the complexity of predicting the unusual December floods that drenched the state in 2023 — and which were threatening a repeat this December.