By Erin Petenko/VTDigger

Vermonters pocketed a median annual household income of $72,431 from 2017 to 2021 and are less likely to live in poverty than they were a decade ago, according to the latest data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

At first glance, the data — collected via surveys of thousands of people — shows Vermont’s economic outlook improving in the past few years. But a closer look at statistics on housing, income inequality and the labor force paint a more complicated picture.

A median annual household income of $72,431 is a roughly 25% increase over the previous five-year period, or an 11% increase when adjusting for inflation, which in recent years reached record highs. Earnings for working Vermonters also rose 12% over that time period, accounting for inflation.

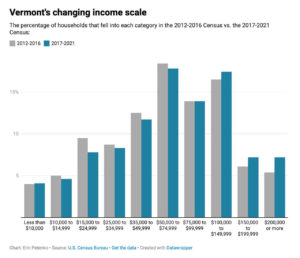

Chart shows Vermont’s changing wealth as a percentage of households by income category.

Peter Nelson, a geographer at Middlebury College, noted that the percentage of households earning more than $100,000 rose between the 2012-16 survey and the 2017-21 survey, from 28% to 32%.

He said that could indicate that Vermont’s rising wealth was concentrated more toward the top of the income ladder, although there are pockets of higher income in the lower end of the scale, too.

It’s too early to say for sure, but Nelson said the change could be connected to Vermont’s inflow of residents during the Covid-19 pandemic. The state gained 4,800 people through migration in the pandemic’s first year, according to earlier Census Bureau data. There is not accurate data on those that came the next year or since — or those that returned home.

Prior to the pandemic, data from the Internal Revenue Service showed that new migrants to the state had higher incomes than people leaving. If that trend continued into the pandemic years, Nelson said, it could explain Vermont’s rising household incomes.

“I don’t think everyone that (moved) during the pandemic would meet this criteria, but the people that have the ability to relocate to what we might call a higher-amenity destination, they’re the ones that have more resources,” he said.

Vermonters also got a boost in 2020 and 2021 from federal Covid aid, according to data from the Public Assets Institute’s annual State of Working Vermont report. Unemployment support, stimulus payments and child tax credits increased the total personal income of Vermonters in those years.

The percentage of people living below the poverty level in Vermont fell in the first two years of the pandemic when Covid-related government payments were taken into account, according to the report. But many of those programs have since ended.

Nelson said the state’s rising incomes should also be measured against the rising cost of major expenses, such as housing. And Census data suggests that many Vermonters have struggled to afford their housing expenses.

Federal estimates label renters as “cost-burdened” if they spend more than a third of their income on housing. From 2017 to 2021, about half of Vermonters fell into that category, roughly the same as in previous years, despite the state’s rising incomes.

Homeowners were less likely than renters to be cost-burdened, but many still are: About a third of homeowners with mortgages spent more than a third of their income on housing costs, according to the Census.

“The struggle may not be… because people are earning less,” Nelson said. “The struggle is that it costs more to live.”

Leslie Black-Plumeau, research manager at the Vermont Housing Finance Agency, said that rental cost burden was a “significant concern” in people’s financial futures.

“Your housing is unstable, and you’re a lot more likely to experience housing instability, eviction, homelessness,” she said. There’s “a slew of problems that come along with just living paycheck to paycheck, and not being able to have wiggle room after you pay your rent.”

The latest Census data shows that, like in previous years, the state had significant income disparities by gender, race and geography.

Chittenden and Grand Isle counties in the northwest had the highest incomes in the state, and both reported a rise in median income after inflation. The Northeast Kingdom’s Essex County, by comparison, had a median household income almost half of Grand Isle’s.

But Chittenden County also had the highest median rent costs and the highest percentage of cost-burdened renters, suggesting that many county residents are still struggling with affordability.

Among full-time, year-round workers, male Vermonters earned 13% more than female Vermonters in the last five years, down from 18% in the previous five years, according to the Census. Women — especially when parenting children under 18 years old — were also less likely to participate in the labor force.

White Vermont workers had higher average earnings than any other racial or ethnic group tracked by the Census, a longstanding disparity even as the state becomes more diverse overall.

Black-Plumeau pointed out that it may still be “hard to see the impact of the pandemic” because the estimates don’t yet include 2022. Housing prices have continued to rise in the last few quarters, according to data from the agency.

“I’m not really sure what will happen when we get estimates that are really all pandemic and post (pandemic), like 2020 on, but we won’t have those higher estimates for a while yet,” she said.