By Katy Savage

When it comes to ski and snowboard tuning, Black Dog Sports owner Dave Manning says he’s like a chef. Manning develops a relationship with his clients. He evaluates the snow and his clients’ ability, and then he puts the ingredients together.

It takes a keen eye and attention to detail to properly tune a ski.

“It’s more like fine dining than fast food,” he said. “If it’s not what you want, talk to the chef and I can help you.”

Manning, a former ski racer, said he wasn’t a good enough skier to have his own technician, so he learned to tune his own skis. He further developed his skills after he retired from racing. Manning spent his summers at Mt. Hood in Oregon and worked for a subsidiary of K-2 called PRE Skis as the east coast technical sales director in the 1980s and early 1990s. He would mount skis, prep them and test them in the summer ahead of the following year’s line.

Manning branched out on his own and launched Black Dog in Killington 27 years ago, where he’s now known across the country for his hand tuning techniques.

“I wanted a dog and I wanted to sleep in my own bed every night,” Manning said.

He got the name Black Dog from his black labrador puppy that came to work with him everyday. While having drinks with a friend from college, the friend pointed to his dog and came up with the name: Black Dog Sports.

“I’ve been a little niche up here for 30 years,” he said. “I’m very proud of it.”

Manning’s clients are manufacturers and locals, though he won’t say too much about his process.

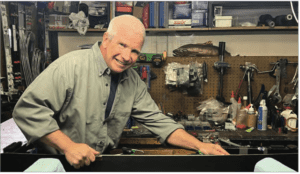

Dave Manning has been tuning skis in Killington for 30 years. He’s perfected a secret technique.

“Trade secrets,” Manning explained one day at his shop, near his black tuning table and wooden ski racks he built himself.

Manning protects the way his skis are tuned like a chef protects a recipe. Manning uses his own “special” wax and his own file stone.

Manning also skis 100 days a year and takes a notebook with him to tests the skis he’s tuned.

“I always ask my customers, ‘When are you skiing next?’” he said.

Those answers help him determine the pattern and the way he’ll shape the ski.

Another secret? Manning starts tuning skis at 5:30 or 6 a.m.

“I can crank my music, the phone’s not ringing, there’s no customers, I can jam out and get it done,” he said.

He does most of it himself, but “like a surgeon” who passes some things to the physician assistant, Manning also trusts his staff with some tricks of the trade.

The geometry of the ski has changed as ski technology has developed and so has Manning’s technique.

“So many people are relying on robotics,” he said.

In a perfect world, Manning admits he would, too.

“I’m a little old and a little set in my ways” he said.

Manning said a robot can’t do everything.

“A robot doesn’t ski, I do. I go up and check out the snow,” he said. “I talk to product managers and I talk to different techs.”

Meanwhile, at Aspen East Ski Shop in Killington, Ted Manning (no relation to Dave Manning), relies heavily on a machine. He can tune 100 skis a night with a large Wintersteiger machine that retails for about $300,000.

“Most of it’s about efficiency,” said Ted, who is also heavily involved in ski racing.

Ted looks at the condition of the ski or snowboard to see if there are rough spots along the edges.

“(The machine) is used to flatten the ski first, then you can set the base edge, then you can put a finished pattern on it,” he said.

Ted can also modify the equipment based on the snow condition.

“The colder the snow, the sharper it is, you typically want a really fine pattern,” he said. “The warmer, you want a more open pattern so the water can get out of there.”

Ted finishes some of the work by hand and can tune it to his clients’ needs.

“There are a million parts to it,” he said. “Every ski that comes in is a little different, every skier is a little different. It changes with every ski.”

Both Dave Manning and Ted Manning agree, “It’s an art, it truly is and it changes,” Ted said.