By Bonnie Kirn Donahue

Squash is one of the easiest types of vegetables to grow. Plant a seed in some soil, give it water and a lot of space and before long you have more than you know what to do with.

However easy to grow, cucurbits are threatened by a number of pests that can make growing these fruits and vegetables much more difficult. One of these pests is the squash vine borer (Melittia cucurbitae).

Squash vine borer

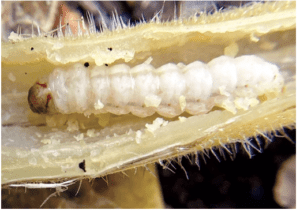

The adult clear-wing moth lays individual eggs at the base of the plant in late June or early July, preferring larger stems over smaller ones. After the eggs hatch, the larval stage of the pest bores into the base of cucurbit plants and feeds on the stem, slowly severing the plants’ food and water supply The larvae pupate and overwinter in the top 1-2 inches of soil, restarting the life cycle.

To check for this pest in your garden, inspect the stem at the base of your cucurbit plants in late July to see if there are feeding holes and frass (pest excrement). Another sign is that the leaves on the plant will begin to crisp and wilt, beginning to die even before the fruit has ripened.

Integrated Pest Management (IPM)is a targeted approach to managing unwanted plants and insects in the garden, starting with observation and identification, followed by treatment methods that start with cultural control, biological control and as a last resort, chemical control.

Cultural control includes using mechanical methods to prevent infestation (such as picking the eggs off the plants by hand or using row covers).

Biological control could mean using a beneficial insect that will prey on the insect. Chemical control uses chemicals to treat the specific life cycle of the pest.

There are a few techniques that the home gardener can try to manage the squash vine borer. One is to scout your plants for eggs in late July. Brown-red eggs are oval-shaped and can be found along the base of stems. If you find eggs, remove them from the stems by hand.

Covering your plants with floating row covers can help to create a barrier between young plants and pests, providing that the pest isn’t already present in your soil from a previous year.

One issue with this method is that cucurbit flowers need to be pollinated to produce fruit, so the row covers will need to be removed during flowering.

In the fall, bag up infected plants into trash bags and dispose.

Other options include breaking up the plant and tilling it back into the soil. Tilling the soil also can disturb the pupae, sending them deeper into the soil to help break the life cycle.

Bonnie Kirn Donahue is a UVM Extension Master Gardener.