By Ethan Weinstein/VTDigger

BRIDGEWATER — At the corners of Barnard, Bridgewater, Killington and Stockbridge rises a hundred square miles of rugged, rocky land.

Twenty-five years ago, the four towns banded together, working alongside conservation-minded nonprofits, to form the Chateauguay No Town Conservation Project, with the goal of conserving as much of the 60,000-plus acres as possible.

The endeavor, known as a regional conservation partnership, was the first of its kind in Vermont.

A waterfall hidden inside the Bramhall Wilderness Preserve exemplifies the unspoiled landscape that the conservation protects.

The Two Rivers-Ottauquechee Regional Commission handled organizational logistics, while the conservation groups — Vermont Land Trust, the Conservation Fund, Northeast Wilderness Trust and the Appalachian Trail Conservancy — procured conservation easements and purchased some of the land outright. All the while, the coalition has relied on voluntary participation from landowners, limiting development to sustain the region’s wildness.

Barnard resident Tom Platner was one of the founding members of the Chateauguay No Town Conservation Committee, which proposed conserving the land in the late 1990s.

More than two decades on, the preserve is a lasting symbol of regional cooperation, land about as untouched as one can find in Windsor County.

Before Platner and his peers drummed up the idea, Chateauguay had long been popular among local hunters and outdoors enthusiasts, and was even the home of a not-so-successful gold rush in the 19th century.

“There wasn’t a ton of roads in there, and there’s no real power. So I mean, to do any kind of development there, it’s pretty, pretty expensive,” Platner said, explaining how the Chateauguay — as locals call the sprawling, rocky preserve — has maintained its relatively unblemished character.

But despite the rough nature of the land, development along Routes 12, 100, 107 and particularly Route 4 has long threatened to encroach on the Chateauguay. The latter is a primary east-west byway across Vermont’s waistband, connecting White River Junction in the east to Woodstock, Killington, Rutland and eventually New York state to the west.

As Platner recalled, representatives from Killington required some extra convincing to begin the conservation work, fearing inhibited development around Killington Resort.

But once all four towns got on board, Platner said the Vermont Land Trust and the Conservation Fund took charge, building relationships with individual landowners to conserve the Chateauguay piece by piece.

Much of the land was once owned and actively logged by timber companies — including parcels owned by Lasell University in Massachusetts and Yale University — and logging continues today.

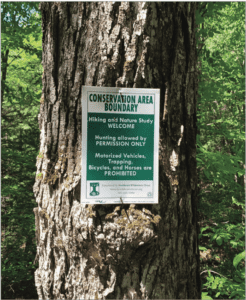

The Northeast Wilderness Trust is one of several conservation groups that facilitates preservation of lands in Chateauguay.

While those involved in the last two decades said enthusiasm about the project has ebbed and flowed, conservationists have nonetheless continued to chip away at protecting more and more acreage inside the mountainous preserve.

In 2020, visual artist Paedra Bramhall, who was born in the Chateauguay, donated 359 acres for forever-wild preservation.

Last year, the Forest Legacy Program — a U.S. Forest Service and state partnership encouraging conservation of private lands — awarded $2.5 million to the Chateauguay partnership, and almost half a million more dollars this year, according to Kate Sudhoff, Forest Legacy Program coordinator at the Vermont Agency of Natural Resources. While appraisals and surveys of the desired parcels are still underway, Sudhoff said those funds are expected to conserve over 3,000 acres of land through coordination by the Conservation Fund.

By necessity, there’s a patchwork quality to the lands conserved inside the Chateauguay.

Bob Linck, who worked on the Chateauguay project while at Vermont Land Trust and now serves as conservation director for the Northeast Wilderness Trust, recalled the array of different land holders with whom he and colleagues negotiated easements.

They included well-to-do conservation-minded types from Connecticut, and born-and-raised Vermonters who could trace back their connection to the land for hundreds of years. He credited the grassroots support for Chateauguay No Town and the one-on-one relationships built with landowners for the project’s success.

According to Abby White, vice president of engagement at Vermont Land Trust, 15,700 acres are currently conserved within the region. That includes the almost 8,000-acre Les Newell Wildlife Management Area, Vermont Land Trust easements and the Appalachian Trail corridor.

As Pete Fellows, who coordinates the conservation project for the regional planning commission, explained, the Chateauguay serves as a vital link between southern and northern sections of the Green Mountain National Forest.

“That’s really important for ecosystem resilience and adaptability for climate change as the climate moves north, or, as you know, these climate regions march north,” he said.

Federally protected parts of the Green Mountains cover huge parts of the southern and central parts of the state, but a large gap exists in between. Chateauguay No Town, as well as a similar partnership in Mount Holly, bridge that divide, providing a safe path for wandering wildlife. This landscape-scale conservation better sequesters carbon and protects watersheds, Fellows said.

Miles of small streams plunge from the higher elevations in the center of the Chateauguay, including brook-trout-rich headwaters of the Ottauquechee, and feeder streams of the White River like Locust Creek, which provides important spawning grounds for wild rainbow trout. In spring, fiddleheads and ramps pop up beside the streambeds. By July, bright orange chanterelles punctuate the green landscape. And come fall, the brook trout color up to match the foliage, triggered to mate by autumn rain and plunging temperatures.

Through surveying the area’s forests, ecologists have located regionally endangered and threatened species, and designated the entire parcel as a bear production area, meaning it’s home to high numbers of offspring-producing females, according to the regional commission.

Platner, the Barnard resident who helped create the conservation partnership, recounted walking through groves of Beech trees and spotting bear “nests” — bundles of broken sticks high up in trees where bears sit and eat beechnuts.

Elsewhere, bear hair was stuck to birch trees, their bark gnarled by teeth and claw marks.

Other times, Platner stumbled upon moose wallows, pits made by male moose during mating season.

“You could even smell it. [The moose] gets there and pees in a hole and gets it all over their chest and beard and waits for the females to come to them. Nothing worse than a horny male,” he said.

Reminiscing on the origins of the partnership, Platner remembered the feeling of creating something novel. Once the project got off the ground, some folks up in Jericho invited him and his colleagues to talk about how it all worked. Those folks wound up creating the Chittenden County Uplands Conservation Area, Vermont’s second regional conservation partnership.

Today, at 74, Platner — who’s had a knee replacement and can no longer explore the Chateauguay like he used to — worries about a lack of participation from a younger generation.

“I would love to see younger people get involved, and I don’t know how to do that. I can’t figure out a way to get them going,” he said.

But, based on the rate at which new lands inside the Chateauguay are being preserved, the project won’t be dying any time soon.