Editor’s note: Julia Purdy is employed as a copy editor for the Mountain Times.

Julia Purdy first read “The Sky is Red,” when she was 8 years old.

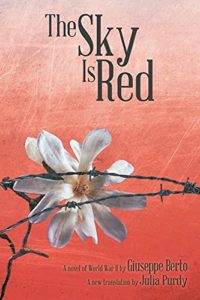

The prize-winning 1947 Italian novel by Giuseppe Berto tells story of four teenagers struggling to survive after being left orphaned when their town in Southern Italy is bombed during World War II.

The book has always intrigued Purdy. Her copy of the original galleys is so old that it’s “just sewn together,” Purdy said. “It doesn’t even have a cover.”

“It kept nagging at me,” Purdy said. “I wanted to breathe new life into it.”

That’s why Purdy, now 76, of Rutland, self-published the book into a new American English translation in 2020.

“I wasn’t planning to make a lot of money on it,” Purdy said. “It was a personal project that I felt had to be done.”

The original author, Berto wrote the book while a prisoner of war near Hereford, Texas. It gets its title from the scriptural quote from Matthew (XVI 2,4) that opens the novel and warns people to read the “signs of the times” in a red sky.

“In all, the novel issues a timeless warning to all nations of the waste and tragedy of war, even those deemed necessary,” Purdy writes in her description of the book.

Purdy sees parallels from the “The Sky is Red,” to issues today. Purdy started her translation in 2017, when U.S. missiles hit an air base in Syria. Now, families in the Ukraine are struggling with the after-effects Russian bombings have had on their cities.

“It’s that story all over again,” Purdy said. “I thought, ‘this never changes, it’s always the same. ‘ Why does anybody think it’s going to be different? It isn’t.”

Purdy plans to offer readings of “The Sky Is Red” at area libraries this summer and fall, and is available as a speaker.

Purdy’s version of the “The Sky is Red,” is available for purchase at Barnes & Noble, Amazon and elsewhere.

The Mountain Times asked Purdy about her experience from translating the book to self publishing.

Q&A with Julia Purdy

Mountain Times: The original version of “The Sky is Red,”is in Italian. How did you learn the language?

Julia Purdy: I didn’t grow up in an Italian-speaking family since my mother remarried when I was 3. Actually I am self-taught from childhood when I wanted to correspond with my Italian grandmother. Then I started visiting there and between booklearning and immersion, I gradually became conversant (though not 100% fluent!).

MT: How did you first come across this book?

JP: : In 1948 my mother was a reporter at the Rutland Herald. This book (in the first English translation) was sent to her in galley form for review. She had served with the Red Cross in Italy in 1944-1945, so she was delighted to have it. I don’t know if she ever reviewed it. It sat in our family bookshelves since then until I “inherited” it.

MT: Why was it important to you to translate “The Sky Was Red?”

JP: Well, it was a back-burner project for years but I have always been interested in Italian 20th Century novels and films. I did my senior paper in high school on neorealism in the Italian postwar novel, translating passages from the work of Alberto Moravia, primarily. So “The Sky Was Red” was just sitting there calling to me until my curiosity just became so great, so the next time I was in Italy, I purchased the original Italian-language novel, “Il cielo e rosso,” (“The Sky Is Red”) in paperback (Rizzoli). It really began more as a mental exercise, but as I got into the novel I realized its impact and now I recognize it as a classic of Italian literature out of the World War II experience, up there with the film classics such as “The Bicycle Thief” and “Open City.” This makes it an important, but almost unknown in America, addition to our understanding of the devastation of war — any war. In fact, as I worked on the translation, Syria was in the headlines, and now Ukraine.

Just a note about the original author, Giuseppe Berto. He was an officer in the Italian army and interned for three years in a POW camp in Texas, where he began this novel. He passed away in 1978 in Italy. The novel is full of eyewitness-quality street scenes that depict the aftermath of a blanket bombing of a small town that Berto does not name but which I have since learned was Berto’s birthplace, Treviso, in the north of Italy. Like many other towns, Treviso was heavily bombed in the Allied effort to drive the German forces up the Italian peninsula. Berto places the fictional town somewhere between Naples and Rome, but it could have been anywhere.The writing is so true to reality that there is no doubt in my mind that Berto knew — or knew of — some of the characters, the underground resistance movement, and naturally the town itself, well. Of especial interest is the interactions with the Americans, leaving Italians with mixed feelings toward their liberators.

MT: What was the translation process like? How long did it take?

JP: I think I first hatched the project just casually, around 2017. It took several months of intermittent but consistent effort, once the project got a grip on me. This is a story in itself! At the time I was living in Rochester and in touch with the people at the Herald of Randolph. They had a contributor, Christopher Costanzo out of Bethel at that time, who wrote hosted an Italian language conversation circle. I approached him for help in some of the dialect and technical terms. As it turned out, Chris actually was in Naples as a child during the time period of the novel in 1945. His father, an Italian-American, was assigned to Naples with the Foreign Service, as the Allies had taken the city and set up an administration post there. So I would do a very rough translation of one chapter at a time, then send my document to Chris for comments and corrections. We did this all the way through the novel. He was invaluable inproviding insights into the culture and conditions of life in southern Italy at that time. I am forever in his debt, although he steadfastly refuses to take any credit!

MT: How does your translation differ from the British translation, if at all?

JP: It was first translated by British author Angus Davidson, in a literary style that seemed (I thought) harder for American readers to relate to. Terms such as “lorries” and the metric system, as well as older literary usages blunt the impact for American readers who don’t shy from hard-hitting imagery and street slang. Many scenes include confrontations between Italian civilians and American soldiery as well as the degradation of the population, I believed that the language must reflect that.

MT: What was the self-publishing process like?

JP: Self-publishing is now a “thing” and there are many, many outfits jumping on that bandwagon, so one must choose carefully. I realized that as a new author, plus the almost totally unknown title, harking back to a different historical moment and not mainstream by today’s tastes, I would have a very hard time finding a literary agent and any mainstream publisher. I also knew nothing about international copyright other than it is a quagmire of unreadable regulation! Fortunately the first publishing house (XLibris) I approached was able to determine I did not need to buy the rights because of the age of the original work. I should also add that, as a translation, the final product is copyrighted to me, since it is essentially a new, if derivative, product. This was explained to me by XLbris.

I had discovered small grammatical errors in the XLbris edition and their customer service started to lag. After going over the entire text with a fine-toothed comb, I finally went with LitPrime for a second edition (shown here).

Vanity presses can be hard to work with, since to cover worldwide time zones and sometimes language proficiency can be an issue. Yes, I paid for the production and marketing, but I will say that at each step of the way I was consulted as the sole owner of the work, especially the cover design. This particular cover image was drawn from Getty Images, where LitPrime has an account… a very luck find. The graphics people and I decided on the background and the font.

It is important to remember, the vanity presses only provide a service, they do not own the work, and there is no “advance.” And every promotion campaign they launch costs more money! Self-publishing is just that — you pay for service!