Experts are holding their breath

By Erin Petenko/ VTDigger

Timothy Plante likens Vermont’s day-to-day Covid-19 data now to the very first days of the virus’s arrival in March 2020.

At the time, little was known about the progress of the virus because PCR testing was so limited, said Plante, an assistant professor at the University of Vermont’s Larner College of Medicine. Two years later, the public faces a similar problem: “We don’t have reported test data to inform the burden of Covid-19 in our community.”

“Tests are widely available, but they are now generally being done at home, and home test results aren’t being reported to the state,” he wrote in an email.

With declining testing, the number that has been a key benchmark of Vermont’s Covid strategy — the daily number of new cases — means less and less about the state’s actual experience with the virus.

“The current surge is under-detected and underreported,” Plante said.

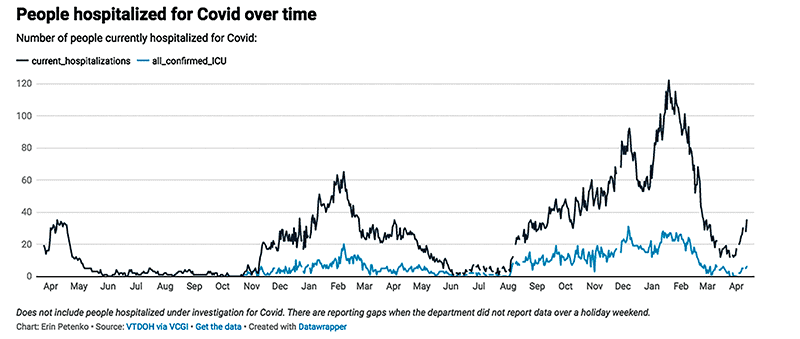

At the same time, other indicators of Covid’s spread have started pointing upward. An increasing number of Vermonters are reporting positive antigen test results to the health department. Wastewater data at several sites shows an upward trend. Covid-related hospitalizations have more than doubled, going from a low of 12 to nearly 30 in the past two weeks.

That may be the result of BA.2, a subvariant of Omicron that is now responsible for the majority of new infections in New England. BA.2 is a kind of first cousin to Omicron, said Theodore Cohen, an epidemiologist at the Yale School of Public Health. The two strains appear to cause similar severity of illness, and those who are infected with one seem to gain some immunity against the other.

But BA.2 is about 50% more transmissible than the initial Omicron variant, giving it the potential to spread quickly. The United Kingdom and other European countries have reported major surges in both cases and hospitalizations.

That track record has experts worried. “The question is if this is the beginning of the next big surge, or if it’s going to be more muted,” Plante wrote.

Cohen said “there is sort of a sense of collective breath-holding” among experts.

“Are we going to see an increasing wave of hospitalizations starting in the next couple of weeks?” he said. “I’m not sure what the answer to that is.”

Vermont officials have painted a more optimistic picture of the virus. Health Commissioner Mark Levine told VTDigger that the latest case data showed that Covid has “plateaued.”

“The increase isn’t on that high upslope that characterized that major peak” for Omicron, he said. “It’s really a prolongation of the tail of the epidemic curve. So that tail is more plateaued with a very gentle upward slope to it.”

At his weekly press conference last Tuesday, April 5, Gov. Phil Scott said officials had never expected that Covid would “disappear.”

“Covid is here to stay for a while, and we just need to learn how to manage it,” he said. “And from the very beginning, it was about managing our health care system.”

How we track Covid

Vermont officials have warned about the waning accuracy of reported case data since the rise of the Omicron variant last December, which coincided with a rise in at-home antigen testing. Antigen tests are widely available and produce results within about 15 minutes, but their results don’t automatically make it to state data systems; users must manually report them to the Vermont Department of Health.

The state’s testing strategy has shifted further in recent weeks, as officials announced that state-run sites would start providing antigen or LAMP tests to take home, rather than PCR tests performed on location.

The weekly average of PCR tests performed has fallen 18% in the past month, even as the case average has risen 64% during that time period, according to the health department.

Anne Sosin, a health equity researcher at Dartmouth College, said she thinks the health department’s daily Covid dashboard “is no longer a reliable source of information on Covid-19 transmission in this state.”

Not only are fewer PCR tests included in the data, Sosin said, but it’s likely fewer people are getting tested when they once would have. That may be because they have mild symptoms, or it may be because public health messaging has deemphasized the urgency of testing.

Scott has repeatedly emphasized that Vermonters should rely on hospitalization data to make decisions, because it covers the state more thoroughly than case numbers and measures the outlook of the more severe forms of the disease.

Levine said hospital data is “reflective of the outcomes that we’re trying to get people to focus on the most now, which are the more serious outcomes for disease severity.”

“We don’t actually know the number of cases,” he said. “We do know the number of people who have had more serious outcomes.”

Plante wrote that looking at hospitalizations and deaths is “appropriate,” but pointed out that “these metrics — and specifically deaths — lag weeks behind surges of Covid-19 community spread.”

“I think that informing Covid-19 community protection strategies based on hospitalization and death metrics alone is ill-advised,” he said. “If deaths are going up, the horse is already out of the barn. We’re too far into a surge to do much about it. The time to implement protections to limit Covid-19 spread is early in surges.”

Asked about the recent rise in hospitalizations, Levine said he is “concerned,” but the recent peak of 30 Covid patients “does nothing in terms of taxing the capacity of our health care system.” Vermont set a record with more than 100 Covid patients in the hospital for two weeks during the Omicron surge.

Levine added that about 50% of Covid patients at a given time are people who came to the hospital for a different reason, then tested positive for the virus while they were there. The health department hasn’t regularly reported that statistic, but Levine said it’s been consistent in the past few weeks.

Wastewater testing, another metric designed to be an early indicator of an incoming Covid surge, continues to take a backseat in analyses of virus data. Four Vermont cities publicly report their wastewater test data, which involves measuring the level of viral segments found in samples of sewage.

Plante called wastewater testing a “promising emerging” metric that doesn’t fall prey to the same issue as case data, with people choosing not to get tested.

“It allows direct estimation of Covid-19 activity for everyone using a toilet that empties to a wastewater plant,” he wrote. “If you look at the Burlington wastewater metrics, historical Covid-19 viral load trend(s) with prior Covid-19 waves.”

Among the four Vermont wastewater testing sites, several data points suggest that Covid is rising. But the data isn’t consistent. “There’s some imprecision in the measurements,” Plante wrote. “The daily measurements jump up and down.”

He said more local municipalities should participate in the program (several are slated to join, but haven’t reported data yet).

Levine said it was also difficult to interpret the wastewater data to understand what it means for communities.

Cohen said he hopes “we start building towards a more sustainable public health response” that includes robust wastewater testing, “to allow us to get a better handle on what’s happening with this epidemic.”

The number of people hospitalized for Covid over time has risen and fallen dramatically since the start of the pandemic.

What do you do for a BA.2 surge?

In previous surges, officials have used Covid data not only to track the progress of the virus, but also to inform policy decisions. “Following the data” has long been the Scott administration’s mantra when justifying changes in lockdown and gathering restrictions, as well as mandates or recommendations about mask wearing.

At recent press conferences, Levine has said the state is shifting toward an “endemic” stage with the virus, in which Covid is a regular, but less pressing, part of daily life.

The health department has limited its mask guidance to personal choice, saying that each Vermonter “can decide if they want to take precautions based on their own personal level of risk.”

Levine said as BA.2 rises, mitigation strategies like indoor mask-wearing become more important for people to “consider,” but not for the state to mandate them, or even strictly recommend them.

“We’ve been trying to allow (Vermonters) to do personal risk assessments and look at their own risk tolerance, look at their own family and community circumstances, and who they expose themselves to or are exposed to, and make intelligent decisions about this,” he said. “And I think by and large Vermonters have figured that out, or are certainly in the process of figuring that out.”

But Sosin said the time for population-wide masking should not be over yet.

“We should prioritize masking in the highest-risk public settings — so, the places where people learn, work, travel, and meet other basic needs,” she said.

Plante said, “if there was a time for mask protections in Vermont, it’s now, when we are likely at the beginning of our next surge.”

Rather than one-way masking — where vulnerable individuals choose to wear masks — he said he supports two-way masking, where everyone in the community wears masks in certain settings. “Two-way masking is key to stop viral spread,” he wrote.

Sosin said Vermont also needs clearer communication from state leadership about the risk of Covid right now and the availability of treatment options. Antiviral therapy is available to high-risk Vermonters who have tested positive.

“If you’re not thinking to go get tested, then you’re not getting access to treatment early in the course of an illness,” she said.

Sosin said that some media outlets are beginning to question, “does it even matter if we see a surge if we don’t count it?” But to her, “it does matter.”

“We will experience a surge even if we don’t capture its magnitude on our dashboard, in the impacts on our health systems or schools or businesses,” she said.

Asking whether we are in a surge, or whether we’ll see a surge, “is the wrong question,” she said. “The right question is, ‘how do we do everything possible to prevent and also blunt the impacts of another surge?’”