By Fred Thys/VTDigger

During his annual budget address on Tuesday, Jan. 18, Gov. Phil Scott proposed taking advantage of federal money pouring into Vermont to encourage more people to move into the state and to train Vermonters to fill thousands of vacant jobs.

“We all see the ‘now hiring’ signs, reduced hours at local businesses and shortages in health care and public safety,” Scott told a joint session of the Legislature.

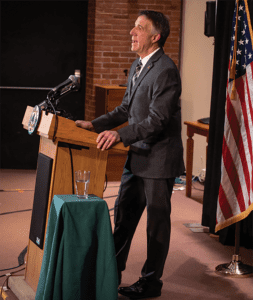

Gov. Phil Scott delivers his 2022 budget address in the Pavilion State Office Building on Tuesday, Jan. 18, 2022.

Among Scott’s proposals were spending $8.5 million over four years to recruit workers to move to Vermont.

Increasing the number of people in the workforce is the primary concern of Vermont businesses, Betsy Bishop, said president of the Vermont Chamber of Commerce. She said looking outside the state is the solution, because “there’s just not enough people in Vermont to fill the jobs that we have.”

She said the cost of housing is one of the main obstacles to persuading people to move to Vermont. People are willing to move to Vermont “to take jobs or even take their own remote jobs with them, but they cannot find enough houses in Vermont,” she said.

Similarly, Jordan Giaconia, public policy director at Vermont Businesses for Social Responsibility, said he has heard plenty of stories from employers who hired people from out of state, only to have them back out when they found out how expensive housing is in Vermont.

The governor proposed using $15 million from the federal American Rescue Plan to encourage construction of homes for middle-income Vermonters, $25 million for grants to landlords to fix rundown and vacant housing, and $105 million to construct mixed-income housing.

He also proposed increasing tax credits by $5 million a year to encourage development in downtown areas and villages.

Beyond housing, Scott said he supports adding police officers, nurse practitioners, electricians and other occupations with an acute shortage of workers to the list of jobs that transplants can take when they are reimbursed for moving to Vermont.

Meanwhile, Sen. Michael Sirotkin, D-Chittenden, chair of the Senate Committee on Economic Development, Housing and General Affairs, said his committee is considering getting rid of the list altogether, letting demand determine which jobs people fill.

Sirotkin said he supports Scott’s emphasis on the trades. The governor said he wants to spend more on internships and training, adding $1 million to the state’s internship program and another $1 million for grants to people who want to train for jobs such as emergency medical technicians and web programmers.

He wants to invest $2.7 million in a pilot program to connect students from career and technical education centers with employers. The pilot program would start with the technical centers linked to the high schools in Barre, Bennington, Brattleboro, Burlington, Rutland and St. Johnsbury.

“We need to focus on the trades, especially with today’s critical need for housing and broadband,” Sirotkin said in an email.

But Sirotkin expressed concern about a proliferation of training programs.

“We need to pay attention to the fact that we have too many uncoordinated programs when it comes to workforce training,” Sirotkin said. “We have plenty of money and obvious need, but it’s spread out over just about every agency in state government with too many boards and not enough coordination.”

Workforce reductions

From February 2020 to November 2021, the latest month for which there are statistics, nearly 24,600 Vermonters left the workforce, according to the Vermont Department of Labor.

Where did they go, and, as the Vermont Department of Labor’s Mat Barewicz put it, “Are these people going to go back?”

“That is the biggest mystery right now,” said Barewicz, the director of economic and labor market information.

Tracking reductions in Vermont’s workforce is an imprecise endeavor.

For one thing, the data doesn’t indicate how many people are over 60, under 18, or whether the number of people leaving the workforce is evenly distributed all ages, Barewicz said. He said early data suggests people from all age groups have pulled back from the workforce.

Barewicz said some are aging out of the workforce and others are reevaluating their work life. Significant disruptions in child care and education are among the factors contributing to those decisions, he said.

Indeed, Giaconia told the House Committee on Commerce and Economic Development Wednesday that, in a 2020 survey conducted by his organization and the Main Street Alliance of Vermont, 42% of business owners reported a lack of child care was an obstacle to people returning to work.

Also during that hearing, Bishop told the committee that businesses are starting to offer salaries instead of wages in an effort to retain employees, which could lead to fewer workers working more than one job.

Barewicz said many Vermonters hold more than one job because so many work in seasonal businesses.

One thing is for sure: A lot of Vermonters have been quitting their jobs. In October, the last month for which data is available, 15,000 Vermonters were hired and 10,000 people quit their jobs.

Meanwhile, the number of businesses opening in Vermont has apparently accelerated during the pandemic — although Barewicz said that could be a quirk of recordkeeping. Between the second quarter of 2019 and the second quarter of 2021, he said, 1,921 businesses opened in Vermont, a growth of 7.8%, compared with 1.8% for the prior two years.

However, he thinks the numbers could reflect workers for out-of-state companies moving to Vermont, with their companies having to register in order to handle taxes for those employees.