In towns with no zoning, reopened Supreme Court decision has big implications

By Emma Cotton/VTDigger

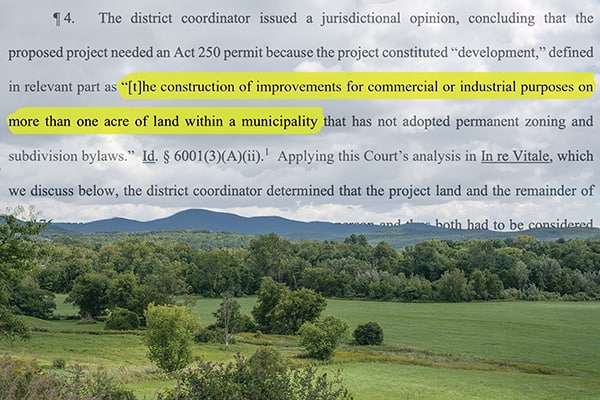

A recent decision issued by the Vermont Supreme Court would change the way Act 250, Vermont’s sweeping land use and development law, functions in towns without zoning and subdivision regulations.

If it stands, the decision related to a proposed stone quarry in Cavendish would exempt certain commercial and industrial projects that Act 250 has historically covered, reversing the way the act has been administered for 50 years.

The ruling by the five justices was unanimous.

But the court has also reopened the decision for reargument, and four parties have opposed the court’s decision.

A decision by the Vermont Supreme Court, which interprets the sweeping land use law differently from how it’s historically been applied, would make it easier for commercial developers to construct projects in towns with no land use regulations.

Opposing groups include two that were originally involved in the case — the appellant and the Natural Resources Board, which administers Act 250 — along with the Vermont Natural Resources Council and seven former Environmental Board and Natural Resources Board chairs.

Currently, in towns with minimal land use laws, commercial and industrial developers need an Act 250 permit when they’re constructing projects on a parcel of land that is, in total, 1 acre or larger.

Under the new interpretation of the law, Act 250 would be triggered only if a developer used — physically disturbed — an acre or more.

“The act does not seek to subject every decision regarding land to government scrutiny or impose restrictions on the alienation of land for their own sake,” read the decision written by Vermont Supreme Court Associate Justice William Cohen.

The Vermont Natural Resources Council, which objects to the decision, argues that the interpretation would allow developers to construct any project with a footprint smaller than 1 acre — 43,560 square feet — in towns with few other means of regulating them. (A football field, for comparison, is about 1.32 acres.)

The decision doesn’t align with the Legislature’s intentions when it created Act 250, says an amicus brief filed by the council. The legal case around the Cavendish stone quarry has been going on since 2017. A local Act 250 district coordinator decided the quarry needed a permit, then the Environmental Court decided it didn’t. Neighbors appealed the case, which went to the state Supreme Court, which upheld the Environmental Court’s decision.

“If it stands, the new interpretation is an open invitation to design projects that physically disturb less than 1 acre for virtually any type of construction or development — gas stations, convenience stores, shooting ranges, chain restaurants and stores, and anything else a creative developer can imagine,” says a motion to reargue, filed attorney Merrill Bent.

An attorney for Snowstone LLC, the company looking to construct a stone quarry, was not available for comment. A call to the landowners’ attorney was not returned.

‘On more than 1 acre of land’

Act 250, enacted in 1970, was spearheaded by then-Gov. Deane Davis, a Republican, when the burgeoning ski industry prompted rapid development, particularly in southern Vermont. It was intended to curb “unplanned, uncoordinated and uncontrolled” uses of land and “protect and conserve the lands and the environment of the state to (ensure) that these lands and environment are devoted to uses which are not detrimental to the public welfare and interests,” the court decision said.

Developers constructing large projects that come under Act 250 review must work with one of the state’s nine regional district environmental commissions, which weigh 10 points of criteria.

While critics of the law have expressed concern that it can suppress economic growth, it’s also widely credited with helping to protect the rural and wild qualities of Vermont.

Act 250 works differently in towns that have existing zoning and subdivision laws — called 10-acre towns — and towns that don’t. In 10-acre towns, developers must apply for a permit if they want to build on a parcel of land that is 10 acres or larger.

The threshold is purposefully lower for towns without land use regulation. There, developers need an Act 250 permit if they’re constructing “improvements for commercial or industrial purposes on more than one acre of land.”

That raises the question: What, exactly, does “on more than one acre of land” mean — and what is the threshold for triggering an Act 250 permit?

“We find the language unambiguous, at least as it applies to the facts presented in this case,” the court decision reads. “‘The construction of improvements for commercial or industrial purposes on more than one acre of land’ refers to the land actually used for the construction of improvements, rather than the size of the parcel on which the construction of improvements will be located.”

Both the Vermont Natural Resources Council’s brief and the appellant’s motion to reargue the case said the language in the statute is clearly saying the opposite. In effect, they argue that the threshold for triggering a permit should be lower than what the court has found. Act 250 “does not indicate that the construction or improvements must themselves exceed one acre of land to trigger jurisdiction, but rather states that they must be on more than one acre of land,” the neighbor’s motion to reargue said.

Loopholes and lemonade stands

Almost half of Vermont’s towns — 45% — are treated as 1-acre towns under Act 250, and those towns cover roughly 2 million of Vermont’s 6 million acres, according to an amicus brief filed by the Vermont Natural Resources Council. In those regions, “commercial development that was intended to be covered under Act 250 may receive no environmental review at all,” according to the neighbor’s brief.

Cohen’s decision suggests the current interpretation of the law is overly burdensome. The decision gives an example: If a Vermonter owns 1,000 acres of pristine forest and wants to construct a commercial or industrial operation on one of those acres, the landowner would be required to undertake “the burdensome and costly requirements of the act.”

“Every lemonade stand on a parcel larger than an acre could need an Act 250 permit,” Cohen wrote.

However, the Vermont Natural Resources Council wrote that legislators designed more stringent regulation for 1-acre towns, in part, to nudge municipal bodies to enact their own zoning regulations. The decision may “incentivize some towns to do the opposite and rescind regulations in order to reduce state environmental oversight,” it said.

The council’s brief warns that the decision could also invite developers to “deliberately design commercial and industrial projects in one-acre towns to fall under the one-acre threshold of disturbance, creating a loophole in Act 250 that never existed.”

‘Do I need a permit?’

What puzzles Ed Stanak, a former Act 250 district coordinator who worked in Washington and Lamoille counties, is the administrative side of the new interpretation. Most of his work on Act 250 was with small-time developers who needed only minor applications, he said. The first step, he said, was addressing the question, “Do I need an Act 250 permit?”

“For over 50 years, the threshold question was, ‘How much land do you own? Is it more than an acre in size?’” he said. “If the answer was ‘yes,’ then we could roll up our sleeves and begin to talk with the person about the practical aspects of getting an Act 250 permit.”

Now, he said, the landowner would likely have had to determine the exact size of a project — a process that would likely require an engineer — before a coordinator can discuss next steps with them.

“This will increase the cost for the small person… just to find out, for God’s sakes, if they need to get a permit,” he said.

“From my perspective, this is a body blow to Act 250,” Stanak said. “It has very serious implications in the rural areas, which benefit the most from Act 250 review.”