By Mark Bushnell/VTDigger

Vermont Republicans might want to add a name to their pantheon of heroes.

The already-enshrined notables are many and varied; they include Erastus Fairbanks, the Civil War governor who is said to have told Lincoln that Vermont would do its full duty for the Union; members of the Fletcher and Proctor families, who between them held the governor’s office and seats in Congress for years; and George Aiken, whose instinct to fight for the little guy against powerful interests like electric utilities and the federal government served him well during his nearly four decades in statewide office, first as governor and then much longer as U.S. senator.

To that roster, Republicans might want to add the name of Stephen Douglas. From Republicans’ perspective, the Brandon, Vermont-born politician might have one minor— OK, major — strike against him: He was a Democrat. But it was Douglas who struck the ill-conceived political bargain that set in motion the formation in 1854 of the Vermont Republican Party, which quickly gained control of state government.

Nationally and in Vermont, the 1850s were a time of political turmoil. The hottest issue was, of course, slavery. But people also were divided over a variety of other issues, from temperance to trade tariffs to the use of public revenues for infrastructure projects.

In the early 1850s, Vermonters had three political parties to represent their kaleidoscope of opinions. But each party had its own baggage.

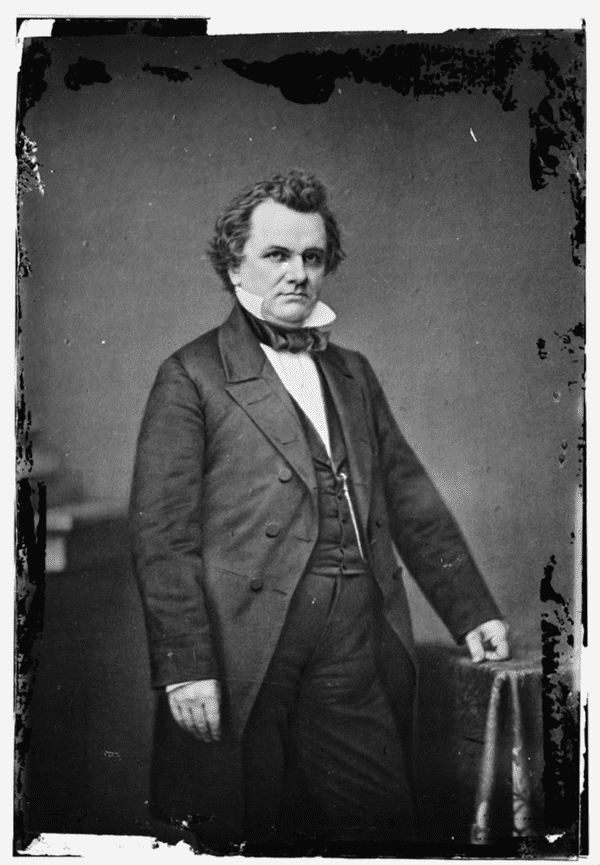

Vermont native Stephen Douglas proposed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, believing it would ease regional tensions and further his political career. The controversial law only inflamed the heated national debate over slavery and indirectly brought about the formation of the Republican Party.

The Democrats were saddled with the reputation of the national party, which relied on the support of Southerners and was, therefore, pro-slavery. While a core of fervid antislavery activists managed to keep the issue in the headlines, most Vermonters wouldn’t have considered themselves abolitionists; that is, though many were strongly antislavery, they didn’t advocate immediate emancipation and the intense and probably violent clashes that would be necessary to attain it. Still, they were hardly friends of the slaveholder.

The Free Soilers, who believed that having free men work the soil was morally and economically superior to slavery, won public support for their stance, but their willingness to form coalitions of convenience with the Democrats damaged their public standing in Vermont.

The third party, the Whigs, were hardly better off. They supported high tariffs and “internal improvements,” what we’d refer to as infrastructure projects, and feared the common folk being allowed too much power. And, like the Democrats, Vermont Whigs were tainted by affiliation with pro-slavery members of their party at the national level.

The degree of political discord in Vermont at the time is hard to exaggerate. The state was so politically divided that nine of the previous 12 gubernatorial elections had resulted in no candidate getting the required majority of votes, so the Legislature had settled those elections.

In the landmark election of 1853, no candidates for statewide office attained the required 50% of votes to win popular election. The Legislature was called upon to pick the winners. But first the House had to elect a speaker to oversee its work, which turned out to be no simple task. With no party holding a majority, the House failed in 30 ballots to elect a speaker.

The Democrats sniffed an opportunity to strike a deal. They voted for the Free Soil candidate for speaker in hopes that Free Soilers would back Democrats in other races. The strategy won enough Free Soil support to gain Democrats the offices of governor, lieutenant governor and treasurer.

But Democrats and Free Soilers tried and failed through 39 ballots to elect a U.S. senator. Most legislators apparently assumed that Samuel Phelps, the Whig who had been appointed to complete the term of a senator who died in office, would be allowed to remain in office. The U.S. Senate had other ideas, ruling that Vermont would be short one senator until it sent a legally appointed or elected one to Washington, so the seat remained vacant.

But all this political disarray was washed away by a single action by Stephen Douglas. In January 1854, Douglas, a U.S. senator representing his adopted state of Illinois, proposed the Kansas-Nebraska Act. It called for the creation of two new territories that would each eventually enter the union as either a free or slave state, as determined by a vote of adult male residents of the regions.

Douglas saw the act as a way of defusing sectional differences over slavery. Some believed he was taking an honorable stand in support of the principle of popular sovereignty, the idea that the voting public could make important decisions affecting its fate. (Never mind the fraught question of whether civil rights should be decided by majority rule.) Others saw rank politics in his actions. Douglas was angling for a run at the presidency, and taking what was then a centralist position on slavery seemed to some to be a cynical move.

Congress approved the proposal, but it didn’t have the effect Douglas wanted. Instead of quelling the debate over slavery, it inflamed it. Slavery opponents were outraged. Douglas’ act effectively replaced the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which had banned slavery in all territories except Missouri that were north of 36 degrees 30 minutes latitude.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act was widely reviled by Vermonters, who viewed it as extreme overreach by the Southern slaveholding powers. And they knew who had done the work for these Southern interests — Douglas and his Democratic Party. With his Kansas-Nebraska Act, Douglas helped assign his party to irrelevance in Vermont.

The state party also had a hand in its own demise. Vermont Democrats understood that the Kansas-Nebraska Act was unpopular in the state, so when they gathered in June 1854, they tried to find a way to both be for, and against, the law. They said they stood with the pro-slavery national party, but at the same time said that support of the Kansas-Nebraska Act would not be a litmus test for membership in the state party.

At the same time, Vermont’s Whigs and Free Soilers were also in flux. The Whigs held a state party convention at which they condemned the Kansas-Nebraska Act and nominated candidates for statewide office. Then top officials with the Whigs and Free Soilers announced they would jointly hold a mass convention in July in Montpelier that was theoretically open to all Vermonters, regardless of political affiliation.

The convention attracted hundreds of Free Soilers, discontented Whigs and anti-slavery Democrats. Those who gathered found commonality on the slavery issue, approving strong anti-slavery positions. They sought nothing less than the repeal of the fugitive slave laws, the end of slavery in all U.S. territories, the abolition of the slave trade, a ban on any new slave states, and the outlawing of slavery in the District of Columbia. These Vermonters joined together under the banner of a new party, the Republican Party.

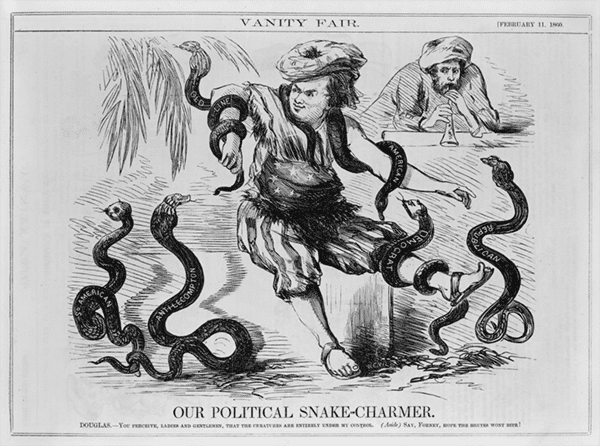

Stephen Douglas was sometimes lampooned for his efforts to calm a variety of political factions to uncertain effect, as shown here in a Vanity Fair cartoon that appeared in 1860 during his run as the Democratic nominee for president in 1860.

The Republicans quickly consolidated their power in state government. By the fall of 1854, Republican lawmakers managed to do what the bickering combination of Whigs, Democrats and Free Soilers could not: select a senator to fill Vermont’s seat in Washington, which had sat vacant for seven months.

The emergence of the Republicans reshaped Vermont politics. The Whigs and Free Soilers soon faded from the scene, their place and political positions having largely been adopted by the Republicans. The Democrats soldiered on, but it would be another century before they won another statewide election. During that century, the only elections that mattered were the Republican primaries, since the party’s nominees were guaranteed to win office.

Today, things have changed for Vermont’s Republicans. Though they have had success winning the governor’s office, they are greatly outnumbered in the Legislature. But it is important to remember that nothing is permanent in politics and that sometimes all you need is a little help from your adversaries.