By Mike Dougherty/VTDigger

As the pace of vaccinations slowed this spring, some experts began floating a new vision of Covid-19’s future as endemic.

Rather than focusing on herd immunity — the threshold at which enough people had been vaccinated or previously infected that the full population would be protected against the disease — endemicity provided a more realistic goal, they said. In other words, the public would manage a certain number of infections, hospitalizations and deaths per year, as it does with influenza or other viruses.

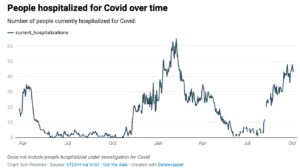

The Delta variant has caused hospitalizations to reach near record numbers, surpassed only by last winter’s peak. Future predictions vary.

That was the reality state officials were planning for early in the summer, Vermont Health Commissioner Mark Levine made clear on Aug. 31. Instead, he said, “the Delta variant threw a little monkey wrench into that whole thing.”

It’s too early to guess when Covid could become endemic, Levine said at the time. Low vaccination rates in other parts of the U.S., and even lower rates around the globe, give the virus more opportunities to spread and mutate. “It’s going to take quite some time,” he said, for those regions to catch up to the Northeast.

But barely a month later, learning to live with the virus has increasingly become a part of Gov. Phil Scott’s stated strategy. Booster shots and upcoming youth vaccinations will provide the necessary protection to bring the more contagious Delta variant to heel, officials have said. In the meantime, Vermonters should take precautions when they feel it’s necessary.

“The fact is, Covid-19, like the flu, is here to stay,” Scott said. “So we need to use the tools we have and what we’ve learned to help people make smart decisions at the individual level.”

Critics have argued that strategy is premature. There is simply too much virus in the state right now to leave mitigation up to individuals, according to many public health experts.

“That word endemic is a misnomer,” said Annie Hoen, an infectious disease epidemiologist at the Dartmouth Geisel School of Medicine. “What we are experiencing with this virus is epidemic waves with exponential growth at times. That pattern calls for aggressive public health intervention.”

In recent weeks, a chorus of public health experts, medical workers, school administrators, state leaders and even rank-and-file employees of the state Dept. of Health have called for stricter mitigation measures.

To them, the data shows that Vermont has reached the worst phase of the pandemic yet. Infections recently have reached record highs in both single-day counts and running averages. Hospitalizations have soared to rates not seen since last winter, and fatalities have kept pace. September was the second-deadliest month of the pandemic in Vermont, and deaths during the Delta wave have surpassed those of the initial surge in March through July of 2020.

Outbreaks have occurred in high-risk settings such as prisons, long-term care facilities and schools filled with children not yet eligible for vaccines.

Yet, administration officials argue that Vermont has weathered the Delta variant better than most states. It is among the three most-vaccinated states in the country, and largely as a result, its hospitalizations per capita are among the lowest. Outbreaks have fizzled out more quickly — and been less deadly — than they might have in the pre-vaccination era, Levine has said.

“I certainly appreciate everyone’s concern and anxiety, frustration,” said Financial Regulation Commissioner Mike Pieciak, who leads the state’s Covid-19 modeling efforts, in a recent interview. “But we don’t want to lose sight that Vermonters stepped up, got vaccinated and really saved a lot of lives.”

But the administration’s singular focus on vaccination rings hollow to Vermonters with kids who still aren’t eligible for their shots, said Senate President Pro Tempore Becca Balint, D-Windham. She and other legislators “can’t go anywhere without people pulling us aside, whether it’s at the bank or the library or post office, the supermarket, saying, ‘Why don’t they understand what it feels like for us to have family members who aren’t vaccinated?’”

“Whether you think we are in trouble depends on your perspective,” said Harry Chen, a physician and former Vermont health commissioner. A fully vaccinated person with no risk factors may see things differently than a health care worker — or a state leader.

“I believe that the public health perspective is that our community transmission is (too) high, Vermonters are getting sick and dying, stressing our health care system,” Chen said. “If you are an elected official, you have to be responsive to your constituents, and there is always a lot of gray.”

Parsing the data

Scott earned a reputation during earlier phases of the pandemic as one of the nation’s most cautious governors. Vermont was quick to adopt preventive measures during the first wave, and the state’s policies on cross-state travel and multi-household gatherings last winter were among the strictest in the U.S.

But as cases ramped up this summer, Scott declined to adopt universal indoor masking guidance issued by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), then deviated from school masking recommendations by the CDC and American Academy of Pediatrics.

When Brattleboro moved to adopt its own universal mask mandate in late August, Scott blocked the measure, saying the town lacked the legal authority to enact it.

Meanwhile, the governor dismissed calls to action by Balint and other state leaders as “playing politics” and cast concerns from outside experts as just online chatter.

Critics say those moves indicated a shift away from a data-driven approach.

“As the evidence has evolved very quickly, I think Vermont’s policymaking has lagged,” said Anne Sosin, a public health researcher and policy fellow at Dartmouth College. “There’s been a reluctance to shift course.”

Scott and his team have said that the evidence is not so clear, arguing that record-high case totals are not the cause for concern they would have been in earlier waves.

“I get it. For many months before vaccines, cases were all we talked about,” the governor said on Sept. 21. But because hospitalization and mortality rates — especially for the vaccinated — have decreased since previous waves, case numbers should be viewed critically, he argued.

Why are once-reliable statistics now being cast as so slippery? According to Pieciak, it’s because major new variables have been introduced this year. Vaccines, then the Delta variant, have so drastically changed the circumstances that data from previous waves no longer provides a benchmark.

“It sort of takes this multiple-level drill-down trying to assess what the actual risk is,” Pieciak said. “And I think it’s frustrating for everybody.”

“I do think there was maybe a misconception — among not Vermonters, I think this more broadly among people in the United States — about, you know, ‘This is the silver bullet, and now we don’t have to worry about it,’” Pieciak added.

Vaccines remain highly effective, but they must be paired with other mitigation measures when community spread reaches high enough thresholds, said Julia Raifman, a Boston University health researcher who tracks state-level Covid-19 policies.

“Vaccines reduce the chances of hospitalizations and deaths. But community spread increases the chances of cases,” Raifman said. “If you let the cases increase and don’t control transmission, then you end up with everybody in a worse situation. And that’s what’s happening in Vermont.”

Covid is contributing to enormous strain on the state’s education and health care systems in ways that effectively aren’t being tracked — learning loss for students sent home from classrooms, logistical challenges for parents, and staffing woes that are putting schools and medical providers at or near crisis points, leaders say. According to Raifman, pressures like those will only be relieved when community spread of the virus drops off.

‘Crisis management’

A few weeks ago, Erin Brady’s third-grade son, Evan, was sent home from school to quarantine. Brady and her husband arranged their work schedules to be home with their son while he shifted to remote learning. Then, on the sixth day of a seven-day quarantine, the school detected a new positive case, resetting the seven-day quarantine clock.

Brady is a high school social studies teacher and a Democratic state representative from Williston, where she also sits on the school board. She said the quarantine-and-repeat cycle has been typical for the first month of this school year.

“When the school phone number shows up, your heart drops,” she said. The feeling is “utter dread: ‘Here it comes.’”

Williston schools have reported 21 cases so far this school year, the second-highest total in the state, according to data from the Dept. of Health. But the case numbers alone don’t reflect the “extraordinary stress” that students, parents and school administrators are feeling, Brady said.

Last year, the state health guidance for schools detailed how to implement universal masking, keep students distanced, manage mealtimes and more.

This year, schools opened on schedule for full-time, in-person learning with just two pages of nonbinding health guidance from the state. Since then, the Agency of Education has made efforts to clarify, then scale back, contact tracing in schools, as well as to expand surveillance testing and more recently implement a “test to stay” policy. All of which have fallen on schools to implement.

Administrators are essentially doing full-time Covid management, setting aside the educational and leadership work they would typically be doing, Brady said. “This is very much just crisis management and triage.”

Schools in at least seven districts have closed outright due to outbreaks, some for multiple-day stretches.

In Brady’s district, every grade from Kindergarten through grade 6 has seen cases and quarantines. But the impact on students remains unclear — neither the district nor the state is tracking the total number of students and days that are affected by closures.

As in most districts, a classroom closure in Williston triggers a “pivot day” to allow students and teachers to get set up for remote learning. In part because there was little contingency planning this year, remote days offer less substantive work for students, Brady said, and they risk excluding families who lack the necessary equipment or child care.

According to the Agency of Education, days during which more than 50% of a school’s students are impacted by a closure will need to be made up at the end of the school year.

“I have people in moments of levity talk about it as sort of a ‘snow day decision on steroids,’” said Jeff Francis, executive director of the Vermont Superintendents Association.

The shifting guidance, coupled with the fact that a disruptive new case could arise at any time, creates an ongoing challenge for school communities, Francis said. “We’re dealing with folks who, I am absolutely convinced, are doing their level best in every regard. And they’re fatigued both by the duration, by the magnitude, by the complexity and by this sort of constant change.”

“It feels like the rest of the state has moved on,” wrote Brian Ricca, the superintendent in St. Johnsbury, in a commentary (page 12). “The rest of the state, eligible for vaccination, has decided that school cases are not their problem, even though one of the best ways to bring down school transmission is to reduce community transmission.”

An ‘incredibly stressed system’

Health care facilities are facing a similar crunch, although for somewhat different reasons. Vermont hospitals “are seriously stressed and stretched right now,” said Jeff Tieman, president of the Vermont Association of Hospitals and Health Systems.

Providers are seeing more patients than usual, and those patients are sicker, Tieman said. That’s largely because many people are catching up on treatments they deferred earlier in the pandemic. But the current Covid surge is increasingly making the situation worse.

Though vaccination rates among doctors and nurses are high, hospital workers are still anxious about the risk of infection from treating so many Covid patients, said Marvin Malek, an internist and hospitalist at Springfield Hospital. “Everyone’s kind of worried that one wrong move and you could catch this,” Malek said. “It’s so intensely contagious.”

Those conditions, among other factors, have worsened health care staffing shortages, leading to ripple effects.

Topline capacity numbers don’t tell the full story, Tieman said. “There can be hospitals in Vermont that are on the precipice of crisis standards of care, which means not enough staff and resources to provide the best possible care for everyone who needs it.”

Right now that’s especially visible in Springfield, as well as in the Northeast Kingdom and Rutland County, Malek said. “We can’t afford for the administration to not do all they can to protect ICU capacity.”

Masking up

If there’s little consensus around where the surge stands, there’s even less about how to respond to it.

Those advocating for a more aggressive approach have primarily focused on a tried-and-true method: a statewide mask mandate.

Recognizing the threat posed by the Delta variant, the CDC in late July recommended universal indoor masking, regardless of vaccination status, for people in counties with elevated case rates.

By mid-August, a majority of Vermont counties fit the CDC’s criteria. But Scott and Levine declined to endorse the agency’s recommendations, instead arguing that vaccinated Vermonters should use their judgment. The state’s current masking recommendations, which were last updated on Aug. 31, still include exemptions based on a person’s own assessment of their environment.

Evidence shows that universal masking policies work, said Raifman, the Boston University researcher. Earlier this month, Raifman, Sosin and other New England-based public health experts recommended that Northeastern states replicate measures like Nevada’s, which, like the CDC guidance, switches mask rules on and off depending on county-level case rates.

Tying mandates to real-time data takes pressure off both policymakers and individuals, Raifman said. “It lets people know that there’s an end in sight, that tells people when to mask on, when to mask off.”

Scott has said that, while such policies may work for other states, they’re not necessary in Vermont. Plus, any statewide measure would require reinstating a state of emergency.

“Let’s just say we do that,” Scott said, referring to a range of mitigtion measures including travel restrictions. “We’re going to create more panic, more fear, and just more apprehension just by doing that.”

Scott and Levine have also maintained there would be tradeoffs to implementing statewide measures, including impacts on mental health, substance use, isolation of the elderly and more.

Raifman said that she and other experts are largely skeptical of closure or lockdown policies at this stage — but she argued that masking should still be on the table.

“Masks are sort of the opposite of lockdown,” she said. “They allow us to be around one another safely instead of having to stay at home. And so they certainly shouldn’t be lumped in with lockdown policies, or stay-at-home orders or work closures, because they actually allow us to keep going with our lives and to do so safely.”

A short-term indoor mask requirement would help Vermont turn the corner on the current surge, said Jan Carney, the associate dean for public health at UVM’s Larner College of Medicine and a former state health commissioner. “The benefit of universal masking in indoor settings is that everyone is more protected when everyone is masked,” Carney said. “I think this could help right now.”

Limited survey data indicates that Vermont’s current recommendations have led to only partial compliance.

Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University have used Facebook surveys to poll Americans on Covid-19 benchmarks throughout the pandemic. According to the results, Vermonters who reported wearing masks in public steadily increased from late July through early September, leveling off between 55% and 60%. That’s compared to the 90% to 95% compliance rate seen throughout much of the winter wave.

The bigger picture

Viewed nationally, Vermont is hardly an outlier with its current policies.

States are roughly split on maintaining emergency orders, according to Ballotpedia. As of Sept. 27, 26 states, plus Washington, D.C., still had orders in place. Most states that had dropped their emergency orders did so well before the Delta wave began, and only two states — Alabama and Arkansas — have since reinstated orders that had previously lapsed.

A smaller minority of states have issued blanket mask mandates for schools and the general public, according to The New York Times. As of Sept. 29, schools in just 16 states, plus Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico, maintained universal masking rules. Only six states, plus D.C. and Puerto Rico, mandate masks in public statewide.

Michael Calderwood, an infectious disease physician who has led the Covid-19 response at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, said any new policies should take into account that unvaccinated people are driving the current surge. Universal mandates issued now could run the risk of frustrating vaccinated people who have so far played by the rules. “I think it is increasingly discouraging to folks to see that when you put these policies in place, those that are most adhering to them are the ones that are already vaccinated, at lowest risk,” Calderwood said. “The people that have done what they can to mitigate their risk are being asked to shoulder the burden because of decisions that other people have made.”

Pieciak said the Scott administration is grappling with that question. More cautious people are already vaccinated, getting tested when appropriate, and in most cases wearing masks indoors. “What more do you ask of that population to do, when they’ve done everything that we’ve asked them to?” he said.

Limited polling data, however, suggests that group may welcome new measures. Multiple national surveys found that a majority of Americans support reinstating mask rules when Covid spread is high, regardless of vaccination status.

Still, Calderwood said, policies that may provide a speedier off-ramp from the Delta wave are being implemented beyond the state level. Those include vaccine mandates for large employers and government workers, as well as vaccine requirements implemented by businesses such as airlines, restaurants and entertainment venues.

“We’re going to have to have policies that make it fairly difficult for the unvaccinated to do some things that are part of daily life,” Calderwood said, in order to convince them to get vaccinated and drive up overall immunity.

The weeks ahead

The Scott administration continues to focus on vaccination as its primary strategy.

The state has embraced the federal rollout of booster shots for Pfizer recipients, staging 72 third-shot clinics for a range of eligible people in the first week since the doses became available. (Those 65 and older, or 18 and older with a high-risk medical condition or qualifying occupation, can sign up now.)

The administration sees boosters as essential, said Mike Smith, secretary of the Agency of Human Services.

“[Covid] is not going to go away,” Smith said. “What we’ve got to do is minimize the impact that it has on Vermonters — minimize it through hospitalizations, minimize it through death. Boosters allow us to do that.”

Youth vaccinations will further close the gap, Smith said. Pfizer is expected to formally request emergency use authorization for 5-to-11-year-olds in the coming weeks.

Vermont is preparing to work with pediatricians to speed the rollout and encourage uptake when that age group becomes eligible, Smith said. “It will be a game changer for schools. It will be a game changer for our population in general.”

The question, experts say, is whether the impacts of these additional vaccination efforts will come soon enough.

Last year, the effects of winter sports, indoor gatherings and holiday travel combined in mid-November to drive a sustained and deadly winter wave.

This year, boosters will need to be coupled with personal caution to avoid the same outcome, said Ruby Baker, executive director of the Community of Vermont Elders.

“The more we can have those boosters in place, and have fewer people gathering who are potentially sick and children who are passing things on, the better off we will be, and the more we can protect ourselves from a holiday surge,” Baker said.

Calderwood, the Dartmouth-Hitchcock official, said projections from the hospital’s analytics institute have improved in the past month. While those models had previously projected peaks of hospitalizations that exceeded those seen in January, they now show the Delta wave remaining less severe than the winter surge.

Still, individual hospitals around the region could remain at or over capacity with those numbers, Calderwood said.

State officials have pointed to declining case numbers nationwide as a signal that Vermont’s Delta wave could subside in a matter of weeks.

But Sosin, the Dartmouth researcher, said that’s no guarantee. Personal mobility continues to increase with fall tourism and the holidays approaching. “I have no reason to believe that we can expect this to just go away,” she said citing some highly vaccinated areas where cases have peaked, like the United Kingdom, are still seeing post-spike plateaus high enough to necessitate preventive measures.

Hospitalizations and deaths are lagging indicators, said Malek, the Springfield doctor, meaning that the health care system is likely to remain strained for weeks after cases recede.

Once kids can be vaccinated, Sosin said, the administration’s talking points will appear more sound. Case numbers will represent significantly reduced risk for all, and conversations about how to live with the virus will be called for.

That time isn’t now, she said. “Right now, it’s really critical that we do everything possible to decrease transmission until we can get kids vaccinated.”