By Erin Petenko and Emma Cotton/VTDigger

Washington, Oregon, California and British Columbia are in the midst of a brutal heatwave that has broken records with 115° temperatures and widespread highs above 100 °.

Rob Barbour helps the construction crew pack up early June 29, when Colchester got above 90 degrees.

It seems unthinkable to imagine Vermont, land of snow and frigid winters, experiencing such a once-in-a-lifetime event. But data and interviews with experts suggest that while Vermont may not become Oregon anytime soon, it is vulnerable to extreme heatwaves — and it may not be ready for them.

The National Weather Service defines a heatwave as three consecutive days of temperatures 90 ° and higher. But state climatologist Lesley-Ann Dupigny-Giroux said research from one of her team members suggests that Vermont’s standard should be 87 ° or higher.

“Ninety degrees is fine [as a threshold] for some parts of the country and the nation,” she said. “Because of Vermont’s location, because of our population not being as acclimated to these really, really high temperatures, 87 is a better threshold for us.”

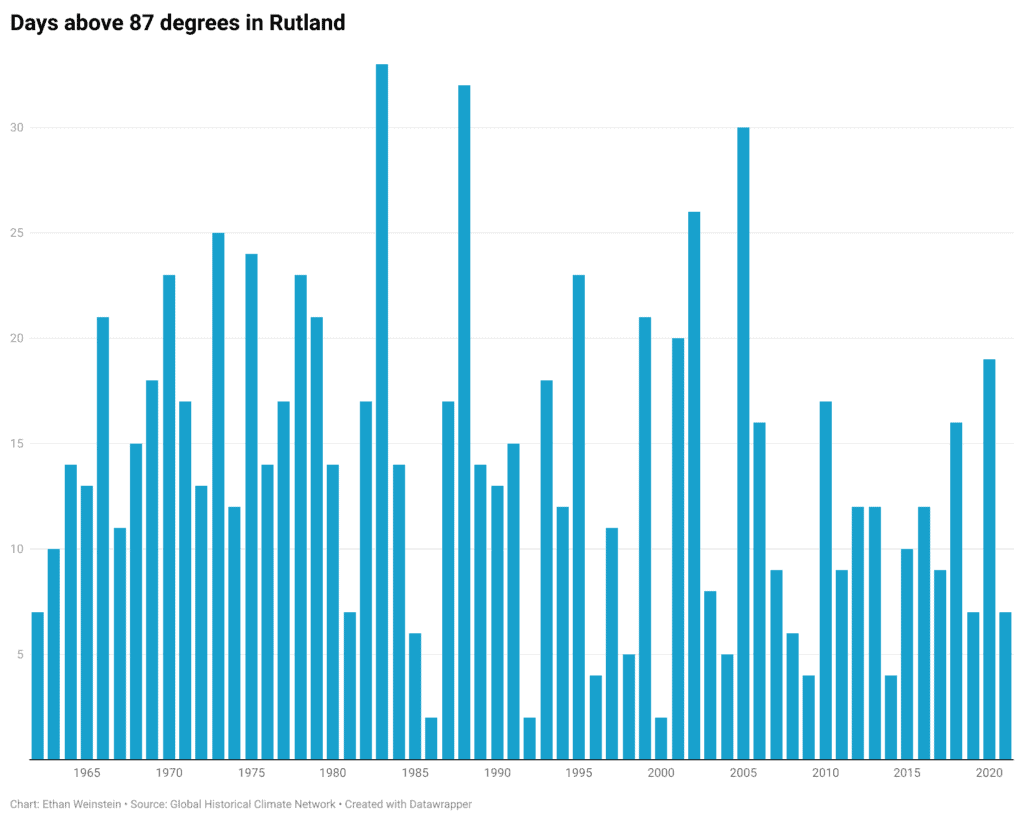

Chart illustrates days measured above 87° — the temperature demarcating a heatwave — in Rutland.

It’s unclear whether Vermont is experiencing more 87-and-higher days because of climate change. While the number of hot days has increased since 2000, Vermont experienced a long period of heat and drought in the 1940s that makes our heat look milder by comparison.

What is clear is that Vermont is just as susceptible to the forces that caused extreme heat out West. There, a high pressure system trapped hot, dry air closer to the ground.

“If you don’t have a lot of moisture, then whatever moisture is there, it’s going to lessen even more, and then those heat conditions just tend to self-perpetuate,” Dupigny-Giroux said.

That interaction happens in Vermont, too: In April, drought conditions combined with hotter-than-normal temperatures to drive heat up even further, creating what seemed like freakishly hot days.

“Dry conditions, high temperatures, low humidities [and] heatwaves kind of go together, because it’s that sort of positive feedback loop that’s going on,” she said.

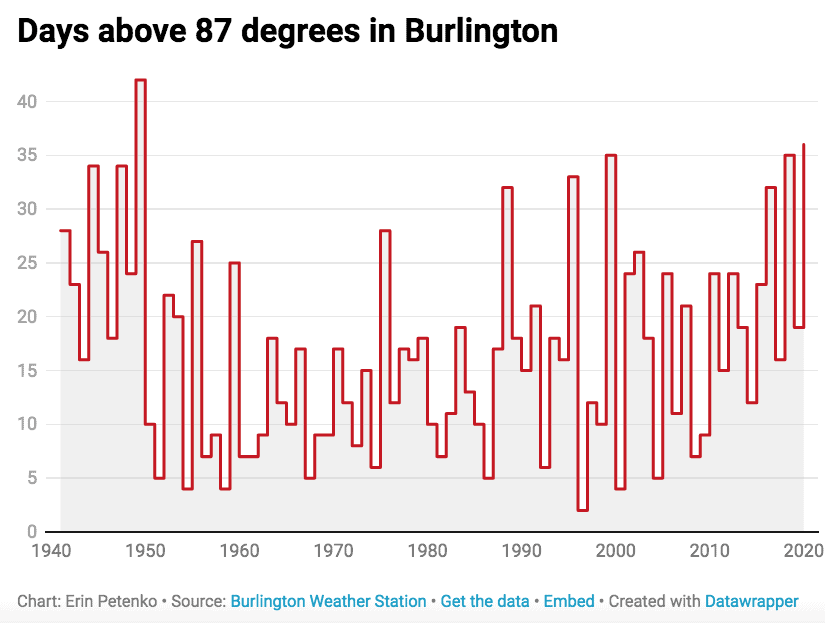

Chart illustrates days measured above 87 ° — the temperature demarcating a heatwave — in Burlington.

Those conditions can occur in summertime in Vermont, too. She gave the example of 1999, when the state had two nearly back-to-back heatwaves in July and another heatwave in early September.

“You couldn’t hike for too long, because the temperatures were so high, right? And then it was so dry, it was also dangerous to be outside,” Dupigny-Giroux said.

She called the West’s heatwave a “teachable moment” for Vermont, bringing focus to the possibility of extreme heat in typical cold, wet regions.

Preparing Vermont for heat

The situation out West is also a reminder of the need for Vermont to prepare to protect its most vulnerable populations, Dupigny-Giroux said, and for the state to use a systematic approach that captures everyone.

“How are we doing this so that we’re not forgetting some people, we’re not forgetting some health impacts or health conditions? How are we doing this, that we’re not forgetting parts of the state? How are we doing it so that we’re not forgetting to reach everybody?” she said.

People who are less mobile, people with disabilities, and older people are particularly susceptible to heat illnesses, like heat exhaustion or heat stroke, according to the Vermont Dept. of Health.

That risk is even higher for low-income people in that demographic because they may not have cooling systems, or be able to afford cooling their home, VDH said.

Data from the Department of Public Service suggests very few Vermonters have extensive cooling systems. A 2015 study of new construction found that only a third of new homes had installed air conditioning, and an additional 13% had room air conditioners (like window units).

A smaller study by DPS from the same year also found very few multi-family residences had room air conditioners. Most newly constructed apartments had central air conditioning, but the majority of older apartments did not.

Hot water

Prolonged heat also affects Vermont’s natural environment, and Oliver Pierson, who manages the state’s lakes and program, said water temperatures in Lake Champlain have increased over time, particularly in the shallow sections of the lake.

“We’re projecting now that Lake Champlain will freeze over, from only once every four years right now, to, perhaps by 2050, freezing over only once a decade,” he said.

Pierson said heat causes a number of impacts on lakes, including reducing the amount of oxygen in the water, and changing the way it handles nutrients. Higher temperatures also create optimal conditions for harmful algae blooms.

All of these factors impact the lake’s ecosystem, and create “additional risks for both water quality and freshwater species living in a lake,” he said.

Pierson said it’s possible with planning to mitigate some of the harmful effects of heat on aquatic ecosystems. It will be important to reduce the amount of nutrients flowing into water bodies, he said. Planting trees and shrubs that provide shade can keep temperatures low along shorelines.

On a broader scale, he said, the best way to affect the escalating water temperatures is to address climate change.

“How do we reduce contributions of heat-trapping greenhouse gases to the atmosphere?” he said. “That’s something that we think about as well.”