By Lola Duffort/VTDigger

At the start of the pandemic, state and education officials worried that Covid-19 would be a financial catastrophe for the pre-K-12 system. Instead, the opposite happened.

With three major federal relief packages approved by Congress since the start of the pandemic, schools in Vermont and the Agency of Education have been allocated a combined $566 million, according to figures provided by the agency.

More than $100 million has already been spent or budgeted on reopening schools, when districts retrofitted buildings to space out students, plowed money into long-deferred HVAC upgrades and bought sanitizer by the barrel.

But the rest has yet to be spent. And while districts will spend significant amounts on recovery and support services this summer and fall, officials also expect money will be left over for projects that haven’t been pursued for lack of funding.

“Everyone’s sort of recognizing that this is a once-in-a-generation opportunity,” said Jill Briggs Campbell, Covid-19 federal emergency management funds manager at the Agency of Education.

Federal aid is coming to schools through several streams, and Vermont largely paid for the upfront costs of reopening schools by using $103 million from the $1.25 billion pot of money Vermont received in March 2020 from the Coronavirus Relief Fund. States were given wide latitude about how to use those dollars on their pandemic response, but a narrow window of time within which to spend it (originally, the end of last year.)

But the money spent on reopening barely touches the dollars that Congress specifically earmarked for schools. The most significant bucket of cash specifically tagged for the pre-K-12 system is the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund (ESSER), which was created in last spring’s CARES Act.

March’s emergency relief fund package sent $31 million to Vermont. The one passed in December sent another $126 million, and the American Rescue Plan Act, signed by President Joe Biden last month, will push an additional $284 million in relief fund dollars to the Green Mountain State.

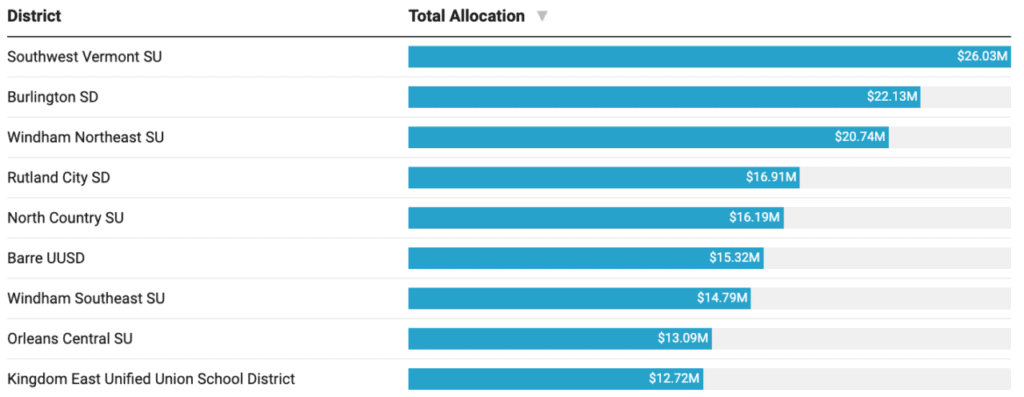

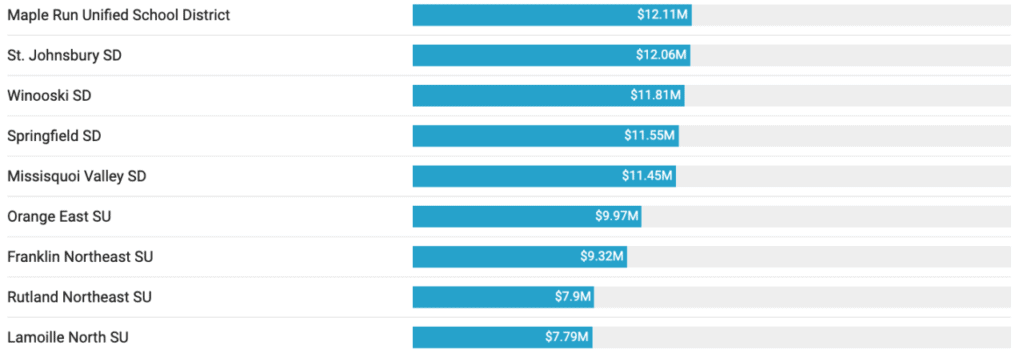

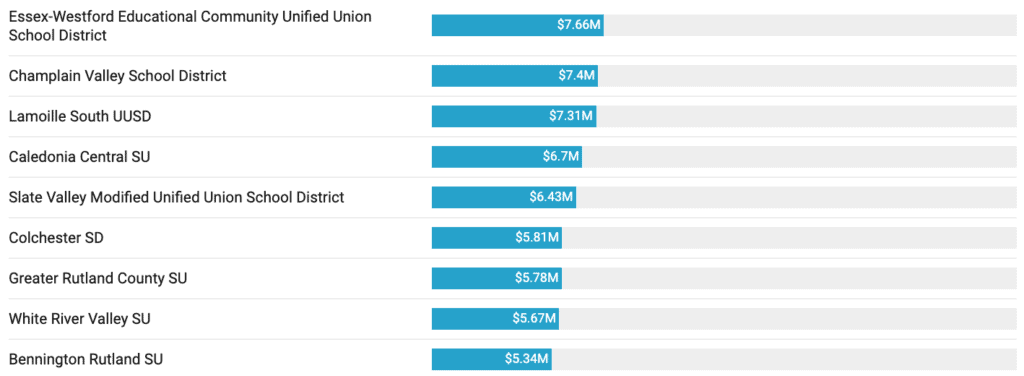

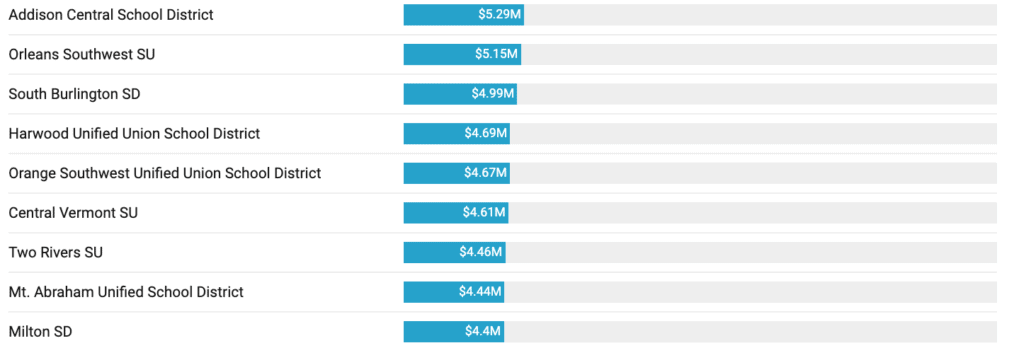

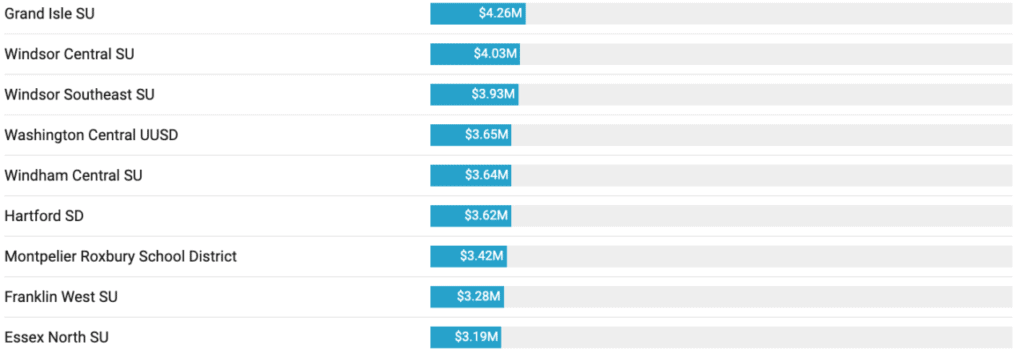

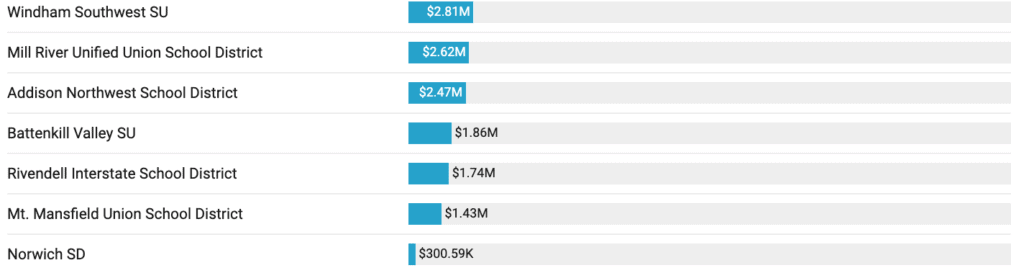

In Vermont, 90% of ESSER funds will flow directly to schools, using a formula that targets high-poverty districts.

How much is your district getting from ESSER I, II, and III?

Table: Erin Petenko Source: Agency of Education Get the data Created with Datawrapper

Schools have already created a plan for how they plan to spend the first batch of ESSER funding. But they have until 2023 and 2024 to spend the latter two, which together account for just shy of $400 million.

“We have an opportunity to not just use these funds for reopening — because we have sort of done that in a lot of ways — but to really use these for those big, sort of intractable problems,” Briggs Campbell said.

Allowable uses for ESSER funds include:

- Special education services

- Activities to address the unique needs of high-risk student populations

- Remote learning and education technology

- Summer and after-school programs

- Learning loss and recovery services

- Mental health supports

- Some school facility updates and repairs, including indoor air quality improvements

One long-neglected area that might benefit from this unexpected influx? Deferred maintenance on buildings. After a decade long moratorium on state building aid, Vermont’s aging schools are facing a bottleneck of major repair and renovation needs.

“I think school facilities stands out,” Education Secretary Dan French said. “We want to help them do whatever we can to help them focus on facilities after they’ve moved on past what the immediate student needs are.”

Springfield school superintendent Zach McLaughlin, where schools are set to receive upward of $11 million through the ESSER fund, thinks the money is an opportunity for “transformational change.”

“I went into some staff meetings and said, ‘Look, I don’t care if you’re in the last year of your career, or really in the first year. This is probably the biggest influx of resources you’ll ever have,’” he said.

While McLaughlin is thankful for the windfall, his emotions are mixed. The money could basically take care of the facilities work the district once again put off when voters defeated a bond proposal at the ballot box in December. But that wouldn’t leave much for the enhanced programming he would like to offer students to help them recover from an extraordinarily difficult year.

And, while coming up with the most effective strategy for using this money should take “deep systems thinking,” his leadership team is flat-out just trying to keep schools operating in the midst of a still-raging pandemic.

“The whole time I’ve been doing this, it’s always been, ‘Let’s do more with less,’ every year. Now I’m in a situation where it’s like the rich uncle has dropped the money in my lap, and the ability to effectively ramp up projects to use that money in an effective way is more challenging than one would think,” McLaughlin said.

Brooke Olsen-Farrell, superintendent in the Slate Valley Unified Union School District, said she’s grateful for the $6.5 million headed her way. The money will likely help the district fund building improvements it has long struggled to finance, and Olsen-Farrell is particularly excited to use some of the money to make permanent the outdoor classrooms that schools created during the pandemic.

But Olsen-Farrell is also nervous about making a plan now — before schools really understand what the long-term impact of the pandemic has been on students.

“We don’t fully understand the entire picture. So that makes it really, really complicated,” she said.