By Julia Purdy

Editor’s note: This is part one in a three-part series exploring the rapidly rising cost of housing, real estate in Central Vermont.

The disappearance of realistically affordable housing is a story that is told over and over, especially in the rental arena. Vermont is in the middle of the pack among all 56 states and territories for highest rental rates, according to Rentdata.org.

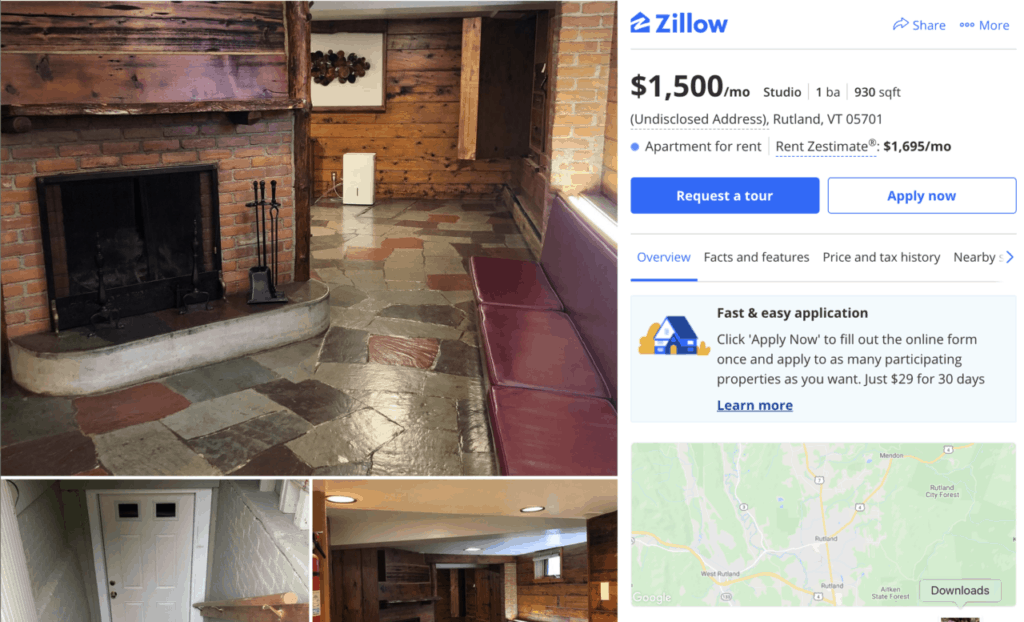

A brief virtual tour around Vermont on Zillow’s interactive map of active listings shows home prices and rents across the board, from $1,628 per month to rent a tiny one-bedroom converted lakeside summer cabin in Colchester to $1,100 per month for a one-bedroom, 900-square-foot ranch with garage in Swanton, and most houses in Rutland city neighborhoods listed for sale in the $250,000 range and up. Deceptively, some properties listed as “house” on Zillow for an affordable $60,000 or $75,000 are actually undeveloped house lots.

“Too many people are paying too much for their housing. An unexpected medical expense, or even a temporary loss of job, means they suddenly are unable to afford their rent,” Massachusetts Housing Assistance Corporation CEO Alisa Magnotta told the Cape Cod Times. “Our region urgently needs to build more affordable housing to ensure that everyone has a safe, stable place to call home.”

The lack of affordable housing is a perennial and growing issue in Vermont, and homelessness is the fallout. Agencies like the housing trusts, housing authorities and nonprofit homeless advocates, and federal housing assistance programs try to keep up with the need by building more subsidized units, but that housing is painfully slow in coming, certainly not keeping up with the surge in open market prices.

Housing vouchers are available for private landlords to accept, but they come with a social stigma attached. New construction, as with the nonprofit Habitat for Humanity, is highly site-based and available land is dwindling.

Subsidized housing providers — not all of them nonprofits — typically use a formula based on various percentages of area median income and HUD’s local “fair market rent” benchmark of 30% of monthly household income to establish not only affordable rents but also to qualify their projects for tax incentives. In qualifying projects, tenants pay 30% of before-tax total household income, although other costs of living, such as medical bills, must come out of that same before-tax income.

Fair market rent includes the typical cost of heat, water and electricity, whether the landlord pays it or not. It is determined annually by the U.S. Dept. of Housing & Urban Development (HUD) using the American Housing Survey, conducted by the U.S. Census with households who moved within the previous 24 months.

Federal funding for such projects is contingent on tying rent levels to the percentage of household income relative to the Area Median Income (AMI), and therefore limiting availability to income-eligible households.

Noting that “affordable” can mean different things to different people, Angus Chaney, executive director of the Vermont Coalition to End Homelessness in Rutland, said the median household income in the Rutland area is about $71,500 (up from $56,139 in 2019; and per capita income was $31,391 in 2018-2019). So 30% of that figure is $26,200. Therefore, the fair market rent would be under $655 per month. To be affordable to such a family earning 50% of AMI, or $35,750, rent would still have to be under $932 per month. Landlords may charge more, but the difference comes out of the tenant’s pocket.

The National Low Income Housing Coalition reported, in 2020, the national average fair market rent of $1,017 for a one-bedroom apartment, which requires a median hourly wage of $19.68. Almost half of all workers in the U.S. earn less than that, the report said.

In Vermont, newcomers from more economically robust areas often choose to rent while they get to know the area and go househunting. What comes across as an exorbitantly priced rental to local eyes looks amazingly cheap to them. Contributing to what some might view as overpricing, “the crisis is unusually lopsided: White-collar employees who can work remotely have for the most part emerged unscathed,” Politico added.

Analysts acknowledge that one impact on affordable housing availability is the so-called “Airbnb effect,” which raises the average rent of an area by replacing long-term, moderate-priced rentals with high-end, short-term rentals aimed at vacationers with disposable incomes. As leases expire or renters vacate, they are replaced not by equivalent housing but by units that are more expensive but stay empty while courting more affluent temporary occupants.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the state of Vermont aggressively wooed well-to-do professionals from southern New England to buy up underproducing or abandoned farms and boost property tax revenues. The process continues, under the name of gentrification. Gentrification is not limited to middle-class educated professionals buying in run-down, and therefore affordable, urban neighborhoods like Boston’s South End. The new owners then move in themselves, or rent to others like themselves, displacing the usually lower-income occupants and raising property values – and taxes – at the same time.

Martin Harris, a Princeton graduate in architecture and urban planning, writing in New Geography in 2012, said, “In both its urban and rural models, [gentrification] is enabled by the newcomers’ advantages in wealth and skills, whereby they can readily afford to out-bid the locals for property…”

In determining affordability of housing, analysts factor in the living wage.

GOBankingRates.com cautions that “living wage” is not the same as minimum wage. The site defines the living wage as “the income you need to cover necessary and discretionary expenses while still contributing to savings. Using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the 50/30/20 budgeting rule — that allocates 50% of your income to necessities, 30% to discretionary expenses and 20% to savings — the study found what you would need to earn to comfortably cover your basic needs while still saving for the future. But the results reveal that the average salary in your state might not be enough to do just that.”

GOBankingRates estimates the annual living wage for Vermont as $77,063, adding, “Living in New England can get expensive, and the Green Mountain State is an example of this. With housing prices nearly 40% above the national average, it costs almost $17,000 a year to live in Vermont. With a median income of $61,973, Vermont residents fall well below earning the annual living wage for the state.”

New Hampshire fares somewhat better, since southeastern New Hampshire has become a bedroom community for commuters who work in Boston, thanks to the expansion of light rail. GOBankingRates says: “While the cost of living in New Hampshire drives up its living wage to more than $68,000 a year, the state also has a lot of residents with higher incomes, leading to a median salary of $76,768 a year. The resulting gap between the two of $8,546 is among the highest that’s most favorable to residents in any state.”

But Maine fares worse, demanding an annual living wage of $75,254. “Residents of Maine are much more likely to be struggling with higher costs than the rest of the country. The annual living wage of over $75,000 is among the highest in the country, but the median income there is on the lower side at just $57,918. That leaves a $17,336 gap between a median salary and a living wage, one of the largest in the study,” according to GOBankingRates.