By Amanda Gokee/VTDigger

With health concerns mounting about PFAS chemicals, the Legislature is moving to restrict the sale of consumer products that contain that class of chemical.

The Senate voted Friday to approve that step; now, the House will consider the measure.

S.20 would restrict PFAS — perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl — in consumer products sold in Vermont. It also includes restrictions on phthalates and bisphenols.

“We know that the chemicals like PFAS, BPA and phthalates can all seep into the foods we eat. We eat them, and they bio-accumulate,” said Sen. Virginia “Ginny” Lyons, D-Chittenden, who sponsored the bill.

“Over time, they can cause some very significant, debilitating diseases,” said Lyons, a college professor with over 30 years of teaching, research and administrative experience in the biological sciences.

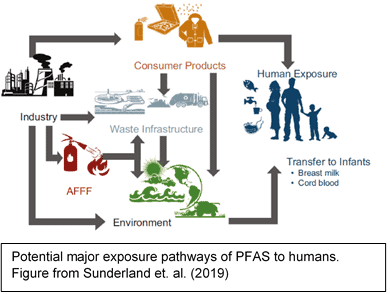

The chemicals have been linked to ADHD, reproductive disorders and neurodevelopmental problems. They have also caused nightmarish problems with the drinking-water supplies in the Bennington area.

PFAS themselves, known as “forever chemicals” because of how long they stick around, have been linked to cancer and other health issues. But the chemicals are common in consumer products because of their water-resistant quality. They’re used in stain-resistant carpeting and rugs, waterproof jackets and nonstick pans.

The bill wouldn’t ban the sale of all products containing the chemical, but it would ban the import and sale of some of the most common items containing the chemical — firefighting foam, food packaging, ski wax, and rugs and carpets. Textiles and leathers with stain-resistant and water-resistant treatments containing PFAS would also be banned.

The bill is a start, said Lauren Hierl, executive director of Vermont Conservation Voters.

“It goes after some of the most common and widespread uses, but it’s not comprehensive. There would be some holes that we would want to continue working on,” Hierl said.

Hierl said that the bill’s intent — to stop PFAS chemicals at their source — is a big priority for Vermont Conservation Voters. A similar bill passed the Senate unanimously last year but was shelved when the Covid pandemic hit. This year’s legislation has added ski wax containing PFAS to the list of banned products.

“We can turn off the tap of bringing these chemicals into the state,” Hierl said.

Firefighters support the ban

Vermont firefighters support the legislation; they say effective alternatives are available that could protect firefighters from exposure to the chemicals.

Bradley Reed, president of Firefighters of Vermont, said the bill would help to regulate chemicals that are linked to cancer — the leading cause of firefighter mortalities.

“We can’t stand by and hope it goes away. We actively have to work to prevent our members from getting cancer,” said Reed, who has been a firefighter for 26 years.

Reed said he wasn’t surprised to learn that PFAS chemicals in firefighting foam could cause cancer but has been surprised by the pushback on regulating the chemical.

In the 23 years that Firefighters of Vermont has been in existence, “we’ve been fighting for the health and safety of our members,” Reed said.

“I wish it wasn’t a fight,” he said.

‘We’ve heard it before’

The American Chemical Council — representing the producers of the chemicals — has been one of the bill’s opponents. It says that, by banning a whole class of chemicals, the bill would ban some chemicals that are safe.

In written testimony, Eileen Conneely, the council’s senior director for chemical products and technology, argued that all chemicals in that class “are not the same,” pointing to “overwhelming evidence of safety when used as components of food packaging.”

But Sen. Lyons said those arguments did not sway lawmakers. “We’ve heard it before,” she said. “A lot of it has to do with trying to confuse folks who may not understand the chemical industry or may not understand how the chemicals are used.”

“The companies that manufacture these chemicals want to continue being able to make and profit off of them,” Hierl said.

Inside the state, opposition has come from Associated Industries of Vermont, a member organization that primarily represents manufacturers. Vice President William Driscoll said the organization does not disclose its membership list.

“We don’t support the bill the way it’s written now,” Driscoll said, including the ban on firefighting foams and the definition of packaging that he believes would affect products that have no contact with food.

In a letter of opposition, Driscoll argued that the PFAS ban would be overly broad and create “unnecessary uncertainty and unintended consequences for consumers, retailers and other businesses.”

Driscoll said that with some amendments, his organization could support the bill.

But Lyons said she was not interested in further narrowing the scope of the restrictions. The definition of PFAS has already been narrowed.

Support from businesses

Some companies in the state, like Seventh Generation, say these restrictions are a good move for Vermont. Director of Sustainability and Authenticity Martin Wolf said the company wants to see the use of these chemicals stopped.

“Once these chemicals get into the environment, as they have with groundwater in Bennington, they are extremely difficult to get out,” said Wolf.

“If we are truly concerned about protecting children and our environment and avoiding the extraordinary cost of cleaning up these chemicals, it’s important to prevent them from being used in the first place,” he said.

According to a study by the Stern School of New York University, companies with a clear environmental, sustainability or social progress mission are outpacing the growth of conventional companies 5-to-1 on average.

According to Wolf, Seventh Generation has been growing at double-digit rates.

“Consumers recognize the need for safer, more sustainable products,” he said. Retailers such as Lowes, Home Depot, Ikea, Walmart and Target have already stopped selling products that contain PFAS.

“This is a really significant bill for our state,” said Sen. Lyons.

If signed into law, the bill would start going into effect in 2022, with other sections going into effect as late as 2023. The senator said this timeline would allow the Department of Health to identify alternative, non-harmful chemicals.