By Lola Duffort/VTDigger

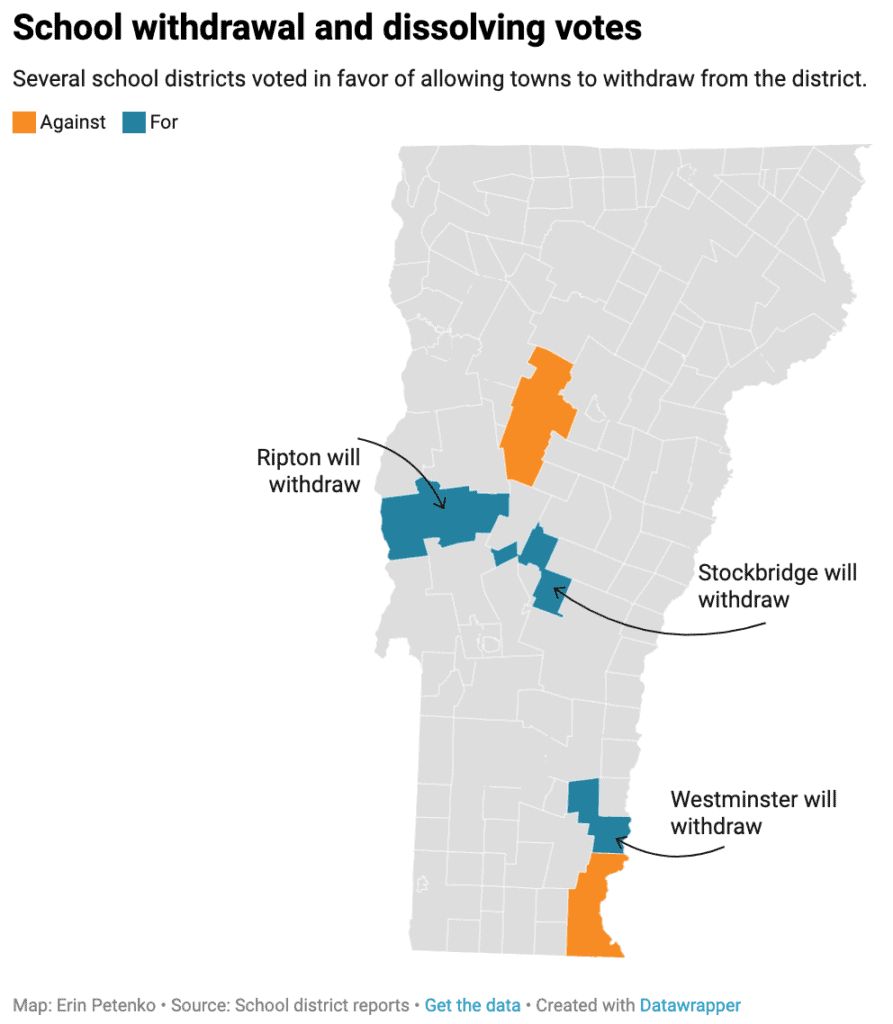

Statewide, petitions to disband unified school districts had mixed results on Town Meeting Day.

In addition to Stockbridge voting to split with Rochester (see story on page 1), voters favored a breakup at the ballot box in the Addison Central and Windham Northeast Union elementary school districts.

But in the Windham Southeast and Harwood Unified Union school districts, voters decided to keep the organizations intact.

Of those votes, perhaps the most closely watched was the results from the six towns in the Addison Central School District, which were asked to let Ripton leave the district. For months, a concerted campaign has been underway to win independence for Ripton, whose small elementary school would be closed under a district cost-saving plan.

Ripton voted in January to ask to secede from Addison Central, and on Tuesday, all towns (Bridport, Cornwall, Middlebury, Salisbury, Shoreham and Weybridge) voted by wide margins to let the town go.

The Addison Central vote is a victory for critics of school district consolidation, who have long argued that mergers would ultimately lead to the closure of small schools.

Margaret MacLean, an education consultant and leading anti-merger activist, pointed out that Addison Central was among the first school districts to merge voluntarily under Act 46, a sweeping school district governance reform passed in 2015.

“The motto of that merged district is ‘Better Together.’ Well, Ripton clearly said we’re not better together, because we’re going to be eliminated. So, we want out,” MacLean said.

Laurie Cox, the Ripton Selectboard chair, who has advocated for secession, said the vote shows the town’s neighbors believed Ripton had the “energy and motivation” to go it alone successfully.

The vote, she said, was “not just for ourselves but for really the future of small towns all across the state which ultimately, in my mind, means the future of the state. We have to find a way to make this successful. The whole state is not, you know, Chittenden County or whatever.”

But many, including Ripton Elementary’s own longtime principal, think “staying open for the sake of staying open” ignores the financial realities that await the standalone school, which educates a little under 50 students.

Tracey Harrington, who has led the school for the last decade, said that, before merging with its neighbors, Ripton perennially struggled to keep spending below levels that would incur property tax penalties.

By winning independence, Ripton may keep its school building, she said. But it stands to lose much of its staff — including her — and access to robust programming through the unified district.

Harrington said she wishes “we could reimagine this conversation,” away from a debate about closing schools and into one about what it would mean to build a 21st-century education system.

“We can’t do that if we stay isolated in our small towns with our small schools. And I worry sometimes that that Vermont mindset of maintaining things the way they are, and resisting change, is going to just set us further back,” she said.

Last fall, a split between two southern Vermont districts demonstrated that a little-known law could give communities a path to independence, if they could persuade all towns within a merged district to vote to allow them to secede.

The breakup of a district must technically go before the state board of education before it is made final, but the board has basically zero discretion over whether to allow the divorce if all towns involved have approved it.

A handful of towns took votes in December and January on the subject of dissolving their unions. The results were also mixed, but most voted to remain together.

It’s still possible that the Legislature could intervene, and in fact, the state board of education has suggested that it do so. But lawmakers have not yet spent any time on a bill tackling the subject, and with crossover — a mid-session deadline for advancing legislation — quickly approaching, it looks increasingly unlikely that they will.

“I had hoped to look at the entire governance chapter, but those conversations have been set aside to address the more pressing issues brought by the pandemic,” said House Education Committee chair Kate Webb, D-Shelburne.