A Merino sheep like those imported by diplomat William Jarvis, propelling the “sheep craze” that swept the state.

By Mark Bushnell/VTDigger

One of the greatest economic advances in early industrial America involved sheep. It also involved Napoleon, an American diplomat and some fortunate timing.

Details of the story might never have come to light if not for the resolve of the diplomat’s daughter, Mary Pepperrell Sparhawk Cutts, to extract the details from her father.

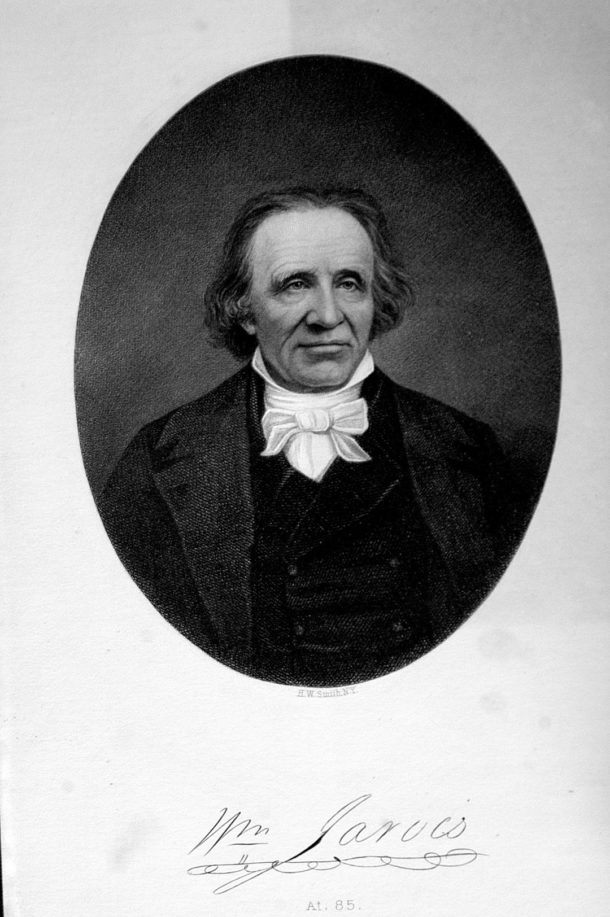

William Jarvis had long resisted calls from his family to write an autobiography. He said that if a great man like Jefferson hadn’t written one, why should he? But Cutts was determined. Late in Jarvis’ life, when he was convalescing from a serious illness on his farm in Weathersfield, Vermont, (10 miles east of Cavendish), Cutts saw her chance.

She began asking him about his life, and making notes of their conversations. Then, like a good biographer, she asked him follow-up questions about crucial events.

From her notes, Cutts published a biographical sketch in the Christian Register, a Unitarian weekly. The next time she visited her parents, her mother asked Cutts whether she knew who had authored the piece. Cutts confessed. No doubt to her relief, her father was pleased with the article. He provided more details about his time as U.S. Consul in Lisbon, Portugal, which Cutts added to her essay and had it published in the Montpelier Watchman newspaper.

William Jarvis helped launch the so-called “merino mania” by importing the Spanish sheep into the United States in 1809 and 1810. Jarvis moved to Weathersfield, Vt., in 1811 to start a large sheep farm.

Cutts then admitted to her parents that she had been working on a full-length biography for two years. Jarvis again argued that he wasn’t worthy of a book, but he relented and even helped correct Cutts’ manuscript.

Jarvis died before the book was completed. Cutts finished the biography and had it published a decade after her father’s death. His demise might actually have made Cutts’ job easier in one way: it gave her access to his papers, from which she drew details about important events, including how her father reshaped the American economy with the help of a particularly valuable breed of sheep.

Skirting the law

“I have been informed that it is not now very difficult to obtain Merino sheep for exportation,” William Jarvis wrote to George Erving, an American diplomat in Spain, in 1809.

Jarvis had learned that another American diplomat in Spain, David Humphreys, had found a way to skirt Spanish law, which forbade the export of Merinos, because Spain’s nobility jealously guarded their virtual monopoly on the breed. Merinos were extremely valuable because of their top-quality wool, which they grew in abundant quantities.

Ordinarily anyone caught exporting Merinos could be forced to work in the mines or on a galley ship, for life.

But now Humphrey had managed to buy 100 of the sheep for his Connecticut farm. Humphrey’s Merinos were the first to reach America, but Jarvis would find a way to dwarf Humphrey’s efforts.

Napoleon was responsible for opening the Merino market. His armies were invading Spain and that nation’s nobility, short on funds due to the war, were

suddenly willing to let some of the sheep go. Jarvis jumped at the opportunity, asking Erving to try to secure him 100 sheep, mostly rams, at any cost “within reasonable bounds,” but admonished him to “(b)e satisfied of their being true merino.”

Erving did better than requested; he bought 200 Merinos from the royal flock. Jarvis shipped the sheep in batches to the United States, not tempting fate by putting them aboard one ship, which could sink, be seized or have an ovine illness sweep through it.

Jarvis’ first shipment included 12 sheep. He told his agent he would sell them for no less than $150 each. Jarvis received a reply from the agent informing him that one of the sheep had died in transit and the other 11 had sold for $1,500 total.

Jarvis was disappointed. They had sold for slightly less than his minimum price. Only later when he reread the letter did he realize that the total figure had actually been $15,000.

This unexpected windfall made Jarvis eager to buy more Merinos.

Fortunately for Jarvis’ business prospects, Napoleon’s troops were now nearing Madrid. The ruling junta was forced to flee. To raise funds, Spain’s rulers confiscated large flocks from nobles who had sided with the French and sought to resell them.

Jarvis leaped at this rare opportunity, purchasing 1,400 Merinos.

Among her father’s papers, Mary Cutts found documents detailing the difficult task of getting the Merinos out of Spain. He collaborated with Col. John Downie, a British Army officer. One official document declared, in case anyone checked, that Downie had legally purchased the sheep, which were certified to have come from the most valued flocks in Spain. Another document that Downie was able to obtain ordered the “military and civil authorities along his route (to) put no hindrance in his way.”

But the French invading army was another matter. Jarvis dispatched his clerk, a Mr. H.H. Green, to oversee the flocks’ safe transport to Lisbon.

“Should the danger from the armies be great,” Jarvis instructed Green, “drive faster, and always in by-roads, such as are most difficult for cavalry.”

Portuguese newspapers reported large military forces along the route. If the reports proved true, Green was to send the sheep in groups of 250 on different roads. Jarvis was hedging his bets, hoping most of the sheep would get through, or seeking to draw less attention to his large flock. He told Green to hire as many shepherds as he needed and not to quibble over their wages.

To Jarvis’ relief, all the sheep arrived safely in Lisbon. Now he had to get them to the United States. Jarvis interviewed several ship captains, asking how best to transport live cargo across the Atlantic. Based on their advice, Jarvis was careful not to put too many Merinos on one ship. He made sure they had plenty of room, air, barley, hay and water. He hired shepherds to accompany them, and paid the ships’ captains and mates a commission for each sheep that survived the voyage.

As Spain’s war with France continued, Jarvis obtained still more sheep, eventually shipping 3,630 to the United States. Virtually all survived the voyages.

It wasn’t just luck. There was a wrong way to transport sheep. In 1810, Jarvis helped Gen. Elias Hasket Derby Jr. of Salem, Massachusetts, procure 1,000 Merinos. The general ordered a ship modified to carry more sheep home. Jarvis advised against packing in so many animals, but the general wouldn’t listen. Nearly half of those sheep died in transit.

Jarvis shipped his own Merinos to ports along the Eastern Seaboard from Maine to Virginia. He sent several sheep each to former president Thomas Jefferson at Monticello and the current president, James Madison.

“(P)ursuing the spirit of the liberal donor,” Jefferson wrote in thanks, “I consider them as a deposit with me for the general good and divesting myself of all views of gain, I propose to devote them to the diffusion of the race through our state.”

Unlike Jefferson, Jarvis didn’t divest himself of all views of gain. He sold more than 3,000 of his Merinos and brought 400 of the best to the 2,000-acre farm he had just purchased in Weathersfield, where he employed 20 seasonal workers to tend his large flock. At his farm, he selectively bred his Merinos and became a champion of the breed, delivering numerous speeches and publishing articles on the topic.

The timing was perfect

The timing of the Merino’s arrival in America was perfect. The War of 1812 blocked access to the British wool market just as American woolen mills were expanding. Domestic Merino flocks helped meet the mills’ demand for wool. After the war, import tariffs bolstered the domestic wool market. The price of wool rose 50% between 1827 and 1835 even as American sheep herds, and therefore the production of wool, grew.

Vermont experienced a “sheep craze” that changed the state’s landscape. Farmers cleared vast swaths of the state to make way for pastures, which they cleared and made stone walls around.

In 1840, the state had roughly 1.7 million sheep — six times the human population. Some breeding sheep became so valuable that their deaths were marked with obituaries. Yes, obituaries.

Eventually, however, it was Vermont’s sheep craze that died. The price of wool plummeted when Congress lowered import tariffs. Only farmers on cheap land out West remained profitable. Vermont sheep farmers just couldn’t compete.

Jarvis’ motivation for importing the breed probably mixed a healthy dose of self-interest with some concern for the “general good,” as Jefferson advocated. Whatever his reasons, Jarvis’ actions helped provide a good living for countless farmers in Vermont and elsewhere for decades, so perhaps it doesn’t matter.

Mark Bushnell is a historian and writer who lives in Middlesex.