By Emma Cotton/VTDigger

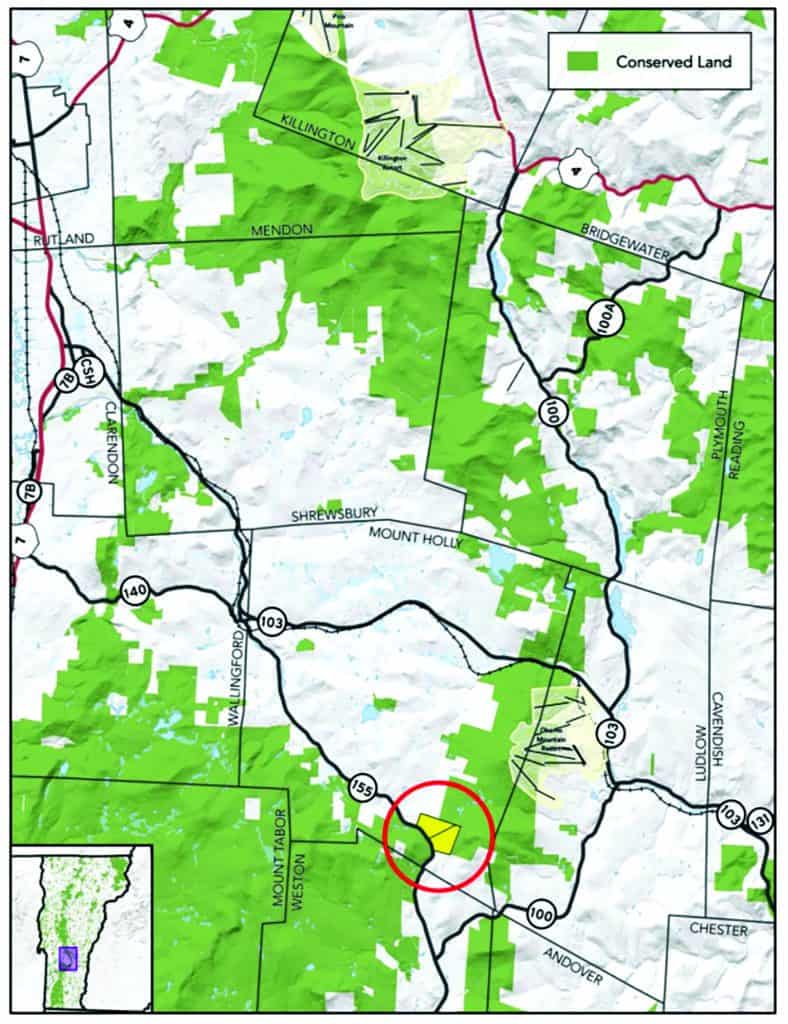

MOUNT HOLLY — A 350-acre chunk of forest with high ecological significance has been protected. The state purchase of the parcel completes a conservation project that protects a 100-mile corridor for wildlife.

The parcel connects sections of the Green Mountain National Forest, Okemo State Forest and Coolidge State Forest. The high elevation and vast forest area provides critical habitat for bears, coyotes, moose and bobcats, conservationists say.

Brigid Sullivan, president of Mount Holly Conservation Trust’s board of directors, said the group recognized in 2005 that the conservation of the parcel was significant because it links a contiguous north-south corridor from the Massachusetts border north to Warren, in the Mad River Valley.

“It wasn’t just connecting the state forest with the national forest; it had this statewide importance then,” she said.

Efforts to complete the 100-mile corridor date back 30 years. In 1985, state officials discovered a bear-scarred stand of beech trees in the corridor that helped them understand its significance to the bear population.

Nancy Bell, a bear expert who retired several years ago from the Conservation Fund, has helped conserve land around the state. She said bears, in particular, need large areas to roam. Male cubs are pushed from their mothers’ home ranges at a year old. Those young animals then need to disperse and seek home ranges of their own, which requires space.

“There’s no more land being made,” she said. “To the greatest extent possible, to conserve whatever we can that is still viable habitat keeps those critters in existence.”

Gannon Osborn, who manages the Land Conservation Program for the Vermont Department of Forests, Parks & Recreation, said the swath of land is an important habitat along the Green Mountain ridgeline. It has high levels of moose and bear activity.

The parcel has wetlands and is the source of the headwaters of the West River, Branch Brook and Mill River, which are now protected. Vermont Fish & Wildlife officials found that the cold temperatures of the Branch Brook headwaters helped to offset warm water from nearby lakes, creating suitable habitat for trout, Sullivan said.

“There’s significant wildlife habitat on this property as well as the greater connectivity of the conserved lands,” Osborn said.

Linkages are crucial

Wildlife corridors become more critical as climate change progresses, Osborn said, because they give wildlife freedom to migrate north or to higher elevations.

“Having both these north-to-south linkages, but also more micro linkages in elevation changes that properties like this offer — it’s really important to provide those opportunities,” he said.

Through Act 171, the state encourages municipalities to protect and connect forests while allowing them to remain open for industries like logging, which takes place within the Okemo State Forest.

The land is already open for recreation — both the Catamount Trail, a statewide cross-country ski trail, and a snowmobile trail managed by the Vermont Association of Snow Travelers run through the property. It’s also open for hunting and hiking.

Mount Holly Conservation Trust raised money for the parcels through private donations. Additional funding came from state and federal programs.

Ian and Kathryn McClean, who live in Pennsylvania but owned a second home on the 350-acre parcel, sold it to the Vermont Land Trust in May 2019 at “a deep discount,” according to the Vermont Agency of Natural Resources.

The land trust recently conserved and transferred the land to the Vermont Dept. of Forests, Parks & Recreation. A house on the property was salvaged by a private buyer.

“It was right on the wildlife travel corridor,” Sullivan said, “right at the base of a really steep rock outcropping where bobcat and lynx and that kind of thing like to hunt and nest.”

Sullivan said parcels like this one are becoming more rare, and she’s glad to see it conserved rather than developed, particularly since Vail Resorts’ purchase of Okemo Mountain Resort in 2018 brought the area new attention.

“The development pressure has gotten much higher, and you could have gotten several houses in there,” she said. “And then you would have lost that whole area for wildlife habitat. So it was really critical.”