By Emma Cotton/VTDigger

Outdated internet services, exacerbated by the pandemic, have plagued residents in rural Rutland County towns.

Now, a new feasibility study provides a path forward for them.

Last spring, Meghan Hill, who teaches English at Fair Haven Grade School, taught classes remotely from her home in Benson, a community with no access to cable or fiber internet.

With a remote learner also in the house, Hill said the push-and-pull for an available 10 megabits per second of DSL connectivity caused her face and voice to freeze or blur during class, and sometimes the Google Hangouts call dropped her entirely.

“You just scramble,” she said. “I was pretty lucky that I never had any problems, that my kids were pretty good.”

In Sudbury, Keith Knapp, a consultant, tries to meet with business partners overseas. Knapp, who grew up in the area, moved away for a job in medical device engineering. He retired early with the idea of running his own consulting business back in his home state.

“I knew what I was getting into with regard to DSL, but I don’t think I realized how painful it would be,” he said. “You can’t really even do an effective Zoom call, for example. You can’t really do video conferencing at all, because the upload speed is so slow.”

Working virtually, Knapp said, is “one of the reasons I came back to Vermont.”

Knapp’s daughter, who attends Castleton University, couldn’t attend her remote classes from his Sudbury home when the college shut down its campus this spring.

Instead, specifically seeking improved internet, she’s renting an apartment near campus. Knapp said he tries to keep the problems in perspective. His family is faring OK in the pandemic, all things considered. But for many individuals — and local economies — the problem is severe.

“At least from my perspective, the ability to be productive in business and industry with crummy connections like that — it’s crushing,” he said.

Four towns shut out

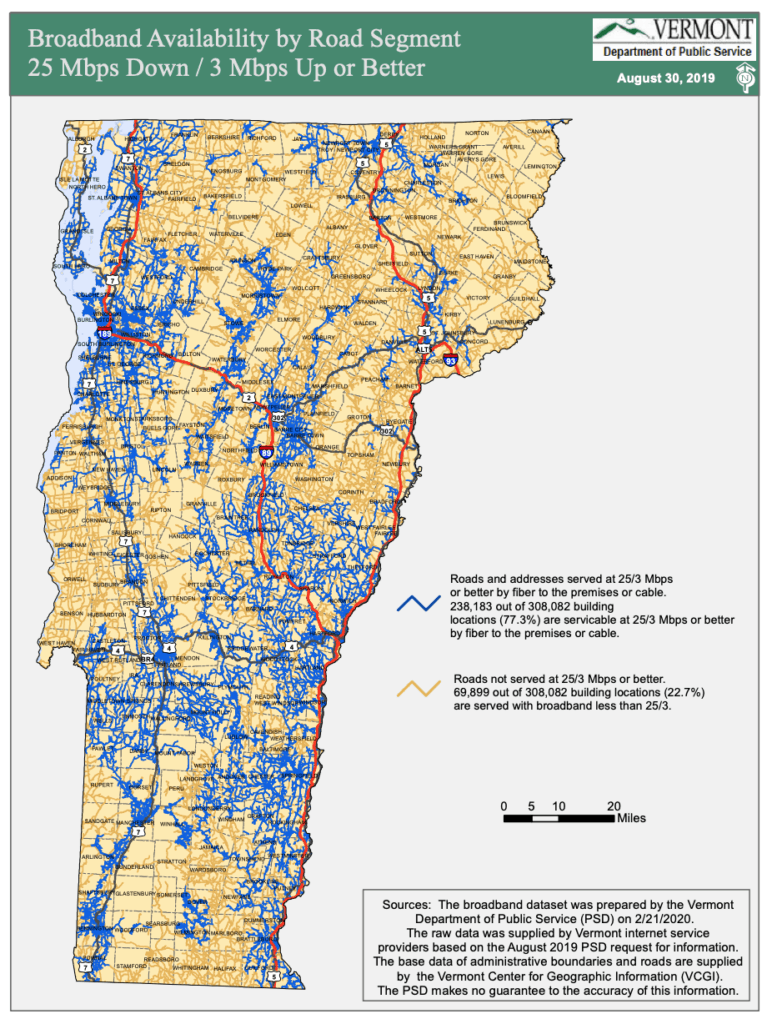

Benson, Sudbury, West Haven and Goshen have no access to cable or fiber internet, and only 10% of Hubbardton has access to those services.

The feasibility study, issued last week, provides suggestions for Rutland County towns with those connectivity problems. Chartered in April through a $60,000 grant, its thesis is hopeful: A communications union district — CUD for short; it’s a municipal entity that pools the resources of multiple towns to guide the expansion of communication infrastructure — is economically viable in the area.

Bill Moore, president of the newly-minted Otter Creek CUD, formed earlier this year in anticipation of the study, stressed that representatives from the organization’s 13 member towns have many decisions to make before creating and expanding the network. Those decisions include choosing a network operator and determining whether they’ll partner with another CUD or remain independent.

As a first step, to assess demand in the area, the study advises the CUD to conduct a pre-subscription campaign to find out what services residents want.

The study was produced by ValleyNet and Rural Innovation Strategies Inc., the organization that recently produced a report offering a number of short-term solutions for the state’s connectivity problems during the pandemic, including using $2.4 million to install internet hotspots around the state.

When the time arrives to begin building infrastructure in Rutland County, the study establishes a build sequence that prioritizes the four towns with no access to cable or fiber.

A familiar story

Moore said stories like Hill’s and Knapp’s are common throughout the rural areas of Rutland County. “You could randomly dial up anybody in Sudbury, Goshen, you know, and get those same sorts of stories,” he said. “Housing deals that fell through because they found that they couldn’t get more than satellite internet. We’re at a point now where we’re being held back.”

The Vermont Legislature voted in 2015 to authorize the formation of CUDs, which act like sewer or solid waste districts.

The state plans to ensure that all residences have access to high-speed internet by 2024, and has encouraged municipalities to form CUDs to that end.

ECFiber, a district that covers much of Windsor County, was formed around 15 years ago and now includes 31 towns, whose residents largely receive high-quality internet. The CUD has been used as a model for other districts.

“Critically, in Vermont,” the study reads, “this legislation also ensures that taxpayers in individual towns are not liable or responsible for mismanagement or failure of the CUD to repay debt incurred in building the network.”

Existing, high-functioning fiber and cables services in the state are focused in its population centers. Within the county, 98.86% of Rutland City and 100% of Rutland Town are served by cable and fiber, for example.

Oh, the geography

In its description of the county, the study gives a sense of the challenges for rural areas. The outskirts of the county are covered by “challenging mountainous terrain,” it says, and have few major roads that run east-west and north-south.

“Existing infrastructure often dead-ends on rural roads and traverses cross-county off the roadway, making it difficult to create a network with redundant distribution,” it reads. “The terrain would also make it difficult for a wireless network to provide universal service.”

A CUD needs 5,000 customers to be economically viable. Two scenarios outlined by the study — partnering with another CUD, or activating independently — predict that Otter Creek will be able to gain that many customers in less than a decade.

If it operates alone, the CUD’s internal rate of return is estimated to be 5.05% — higher than the cost of capital, which makes it financially sustainable — but not as high as the alternative scenario, in which Otter Creek partners with another CUD.

In that case, the rate of return increases to 5.6%. Moore said Otter Creek will likely partner with either Catamount Fiber CUD in Bennington County, or Maple Broadband CUD in Addison County.

Moore called the study the CUD’s “guiding document.”

He said broadband is more important now than ever, with school, work and doctors’ appointments all happening through the internet.

As Brandon’s economic development director, Moore also worries about property values, and the study verifies his concern: Values increase 3% to 5% when the property is connected to fiber. On the other side, the study says lack of sufficient broadband “impacts the ability of homeowners to sell their homes at any price.”

John Hill, Benson’s representative on the Otter Creek CUD, said he has similar concerns in the small town of 907 residents. “There are people who recently moved into town and recently started working from home and the service is really slow,” he said. “Benson is a nice little town with some good things going for it. If we had high-speed internet service, I think it would help the economy a lot.”

The district has more decisions to make before it can act, and for many board members, there’s a learning curve involved.

“We are all neophytes, every last one of us,” Moore said. “But it looks like we’ve got some paths forward we can choose.”