By Emma Cotton/VTDigger

On the flanks of the Green River in southwestern Vermont, the site of an environmental group’s next restoration project is easy to spot.

Near Sandgate’s town offices, the river, traveling west, takes a 90-degree turn to the south. The current collides with a steep hillside, and the curvature of the water has gradually scraped away at the hill’s base.

Cynthia Browning, executive director of the Battenkill Watershed Alliance, said the river’s path toward the sloping land creates what’s called a “firehose effect.”

“It just erodes the bank,” she said. “As long as there’s vegetation on it, it can hold. But as soon as the stream gets through that first layer of vegetation, and it’s in the sand, every time there’s high water, it’s going to take dirt away. And so it starts falling from above.”

Years ago, above the riverbend, a vertical section of earth large enough to hold a house or two collapsed into the river. The resulting swath of exposed, treeless soil, called the “Green River Slide,” now faces the road. Since then, it’s been a familiar geographic feature to Sandgate residents.

Though years have passed, erosion is still taking place there. Beside the riverbend last week, small rocks succumbed to gravity, trickling from high points on the hill toward the stream.

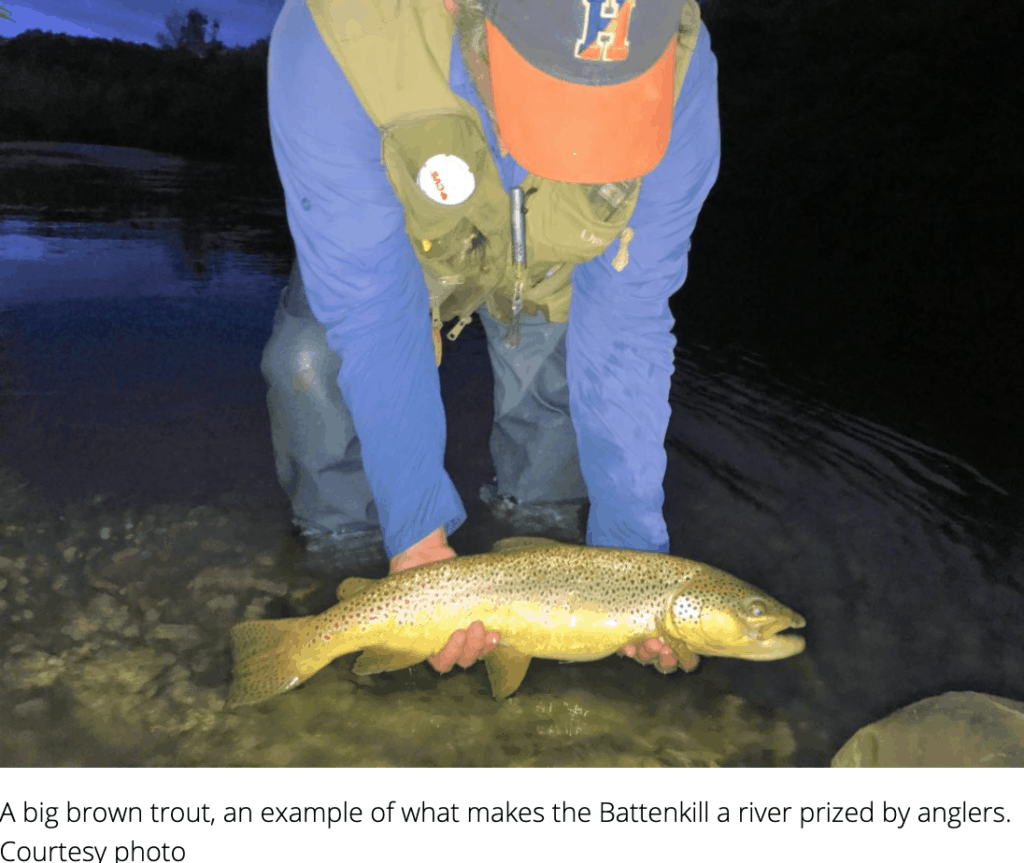

Stabilizing the bank of this river, which empties into the Battenkill — a legendary river to anglers — could help support the population of brown and brook trout. Sediment deposited by the slide makes the riverbed more shallow, increasing the water temperature and erasing deep, cold pools favored by fish. Too much sediment can create unnatural sandbars, which are tricky for fish to navigate, and cover groups of fish eggs.

Stabilizing the banks on this spot in the Green River would be the latest project in a decades-long effort to improve habitat in the Battenkill for trout, whose population declined steeply in recent decades.

Cover and shelter

Because anglers deeply value the river, the national organization Trout Unlimited recently took control of the restoration effort, hiring full-time project coordinator Jacob Fetterman to spearhead the Home Rivers Initiative Project.

Unlike other water bodies in the Northeast, the Battenkill hasn’t been stocked with trout since the 1970s. It’s known instead for its wild fish, which are notoriously difficult to catch. The river is, thus, a source of commerce for southern Vermont — the headquarters of Orvis, an international company best known for its fly fishing gear, is in Manchester, near where the Battenkill winds through town.

Since the 1980s, Vermont Fish and Wildlife has sampled trout populations in the Battenkill on a near-annual basis. In designated sites, fish researchers send electric shocks through the water, temporarily immobilizing fish, which rise to the surface. Scientists gather the fish in nets, estimate the total population in the river by counting the health of the population by documenting numbers, ages and sizes of trout, and release the fish back into the river.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, scientists and anglers noticed the population decline.

Doug Lyons owns a camp near the Battenkill and has been fishing the river for decades.

“Certainly then, in the 1997 through 1999 period, it was very clear that something wasn’t right,” he said. “You just didn’t see the fish like you normally would.”

Scientists had a hunch about why: Development and agriculture in Vermont had wiped the landscape of its trees. Roots stabilize riverbanks and provide shelter for fish — particularly for the young, who need extra habitat to hide from predators.

“It actually turns out that, in effect, fish live in trees,” Browning said. “When you look at a stream, the fish are always where the wood is.”

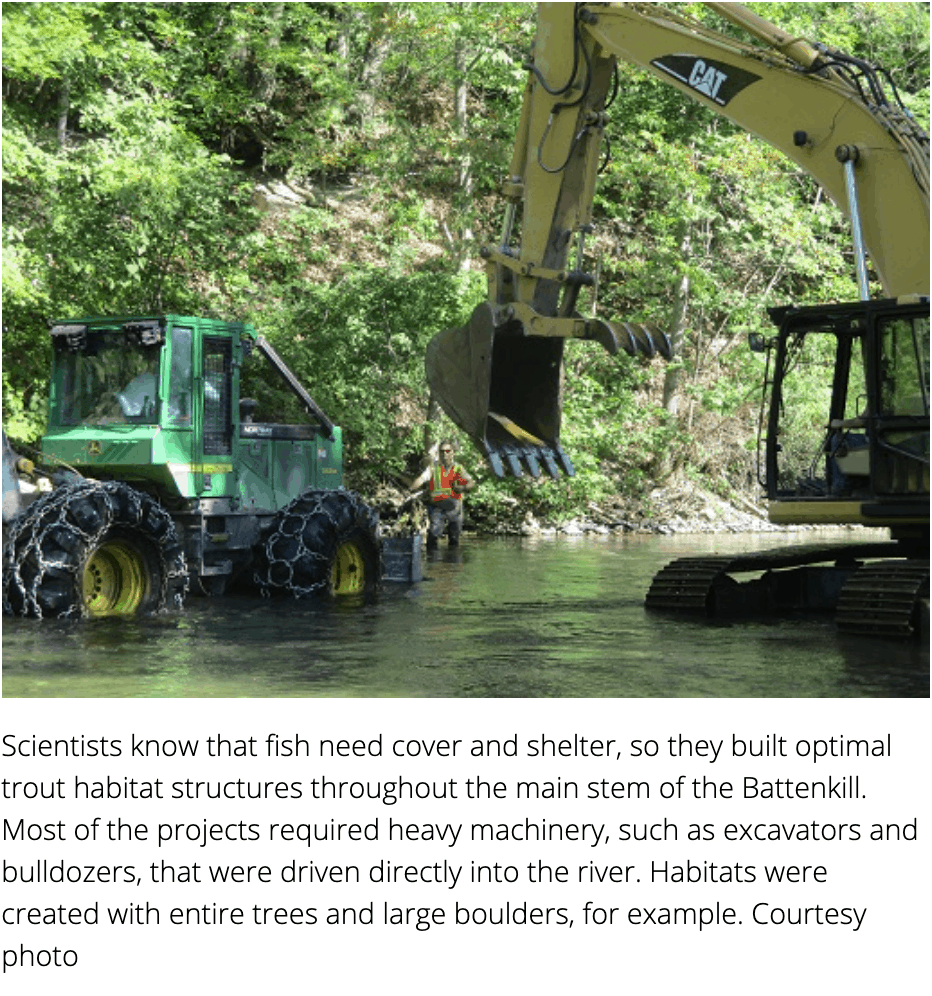

Scientists know that fish need cover and shelter, so they built optimal trout habitat structures throughout the main stem of the Battenkill. Most of the projects required heavy machinery, such as excavators and bulldozers, that were driven directly into the river. Habitats were created with entire trees and large boulders, for example.

Scott Wixsom, a biologist with the Green Mountain National Forest, has been working on restoration projects in the Battenkill since the early 2000s. He helped direct projects that used heavy machinery to build habitat.

“As much as possible, we try to simulate what you would see in natural stream conditions,” he said. “We try to use as little hardware, like cable and rebar, as we can to make the structures appear to be as natural as possible. To do that, we would sharpen the points on the ends of trunks and bolls of the trees and drive them into the stream bank.”

At an angle, the anchored trees slowed the current, and as a result, water was less likely to erode the banks. Their root wads fanned outward, providing shelter for fish.

A year after building 85 of these structures, the results were clear. Numbers of young trout increased by almost 500%, and the abundance of adult trout nearly doubled in some locations.

“Protection and restoration of riparian habitats and its influence on instream habitats will be key to the long-term health of the Battenkill wild trout resources,” concluded a 2011 paper by Ken Cox, a fisheries biologist at the time.

Riverbank stabilization to prevent erosion

With that, scientists from Vermont Fish & Wildlife and the Green Mountain National Forest teamed up with citizens from the Battenkill Watershed Alliance to install the same kinds of habitats in more sections of the river’s main stem, and in its tributaries.

In 2016, the team used large wood to stabilize an eroded riverbank located below the West Arlington Cemetery. Had erosion continued, graves near the top of the bank could have been compromised.

Many similar projects have been pursued in the last several years.

For the “Green River Slide,” Fetterman and Browning think they’re likely to find funding to stabilize the riverbanks, and imagine the project might include using excavators to drive large, sharpened trunks into the riverbank. Fetterman and Browning said this kind of heavy lifting requires a delicate touch.

“Some of the operators are so phenomenal,” Browning said. “This giant machine is like an extension of their arm. I’ve seen them pat something.”

“They can be amazingly gentle,” Fetterman said.

Projects that require this kind of engineering work aren’t cheap. Funding has historically come from organizations like the Trout and Salmon Foundation, Trout Unlimited, members of the Battenkill Watershed Alliance, and Orvis, along with state and federal grants.

Browning said the expense of stabilizing the bank near the “Green River Slide” will be worthwhile.

“It’s maintaining the integrity of the whole system,” she said. “The Battenkill, below the confluence with the Green River, is going to be affected by the excess sedimentation. It affects the habitat there, and then it affects it down in New York.”

While new habitat structures have been continually installed for more than 10 years, Fetterman says there’s more work to be done. Based in New York, his work in the Battenkill watershed, which crosses the state line, is focused as much on growing natural habitat as installing it. Planting layers of trees along the banks of the river, for example, will help provide a sustainable habitat for fish.

“We’ll always be going through this process of identifying projects in various spots, pursuing funding, actually implementing the project,” Fetterman said. “As far as knowing what point we say, OK, we did everything we could, I would say that’s down the road. I don’t know that we’ll ever say, ‘This is a natural environment now,’ but we’re going to get it as good as we can.”

Browning said one of the most difficult parts of the project is persuading landowners to make significant changes to banks near their properties. Having grown up on the Battenkill, when she makes the pitch, she makes it personal.

“We did work on my family’s property,” she said. “That’s how much I believe in what we’re doing.”