By Lola Duffort/VTDigger

Education property taxes could rise an average of 9% next year, mostly as a result of the pandemic-induced recession, new pension obligations and, to a lesser extent, rising school spending, Vermont’s tax commissioner said earlier this month.

This prediction was laid out in the so-called Dec. 1 Letter, a document the department is required to prepare and send to Vermont lawmakers by that date each year. The annual forecast is just that — a forecast — and its projections are in no way set in stone, but they do set the stage for local budgeting decisions and debates at the State House.

The commissioner, Craig Bolio, emphasized the uncertainty at play, and pledged that Gov. Phil Scott’s administration will work to the greatest extent possible to keep his predictions from coming to pass.

“The governor and administration do not believe this is a tenable tax increase for Vermonters who are working hard to recover from the pandemic, nor for the Vermont economy, which continues to struggle due to the pandemic-related disruption,” Bolio said in the letter.

In normal years, the key unknown in December is how much money local voters will approve for schools when they convene on Town Meeting Day in early March. But this winter, the Legislature and local education officials must contend with far larger — and unpredictable — variables. Chief among them is the Covid-19 crisis, which has battered the state’s coffers in unprecedented ways.

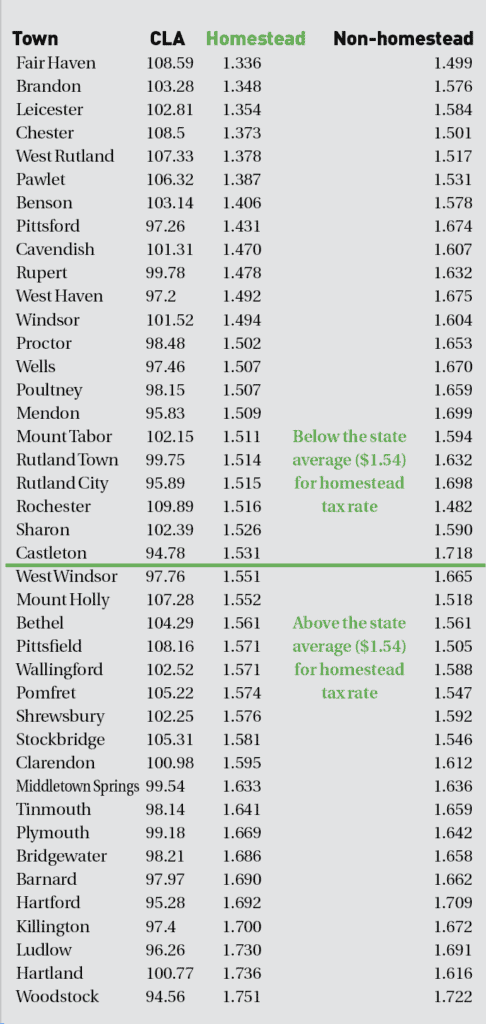

Each district’s education homestead tax rate varies, depending on how much schools spend per-pupil. The average homestead rate this year was $1.54 per $100 in assessed property value — $1,540 on a property worth $100,000. (See table for local rates). If all of the letter’s current assumptions come to pass, the average rate could rise to $1.635.

However, most Vermonters pay their education taxes based on household income, instead. The average rate for non-homestead payers is predicted to rise from 2.51% to 2.74%.

The non-homestead rate, which applies to commercial properties and second homes, could go from $1.63 per $100 in assessed value to $1.73.

The $1.8 billion Education Fund, which pays for pre-K-12 school in Vermont, is fed from property taxes plus a mix of sales, meals and rooms, and purchase and use taxes.

Consumption tax revenues have plummeted in the economic downturn brought on by the virus, and state economists predict non-property tax revenues to the fund will fall by roughly $39 million this fiscal year. That alone accounts for about 4 cents on the forecasted increase.

The pandemic’s impact on tax receipts has been consistently difficult to predict accurately. But how much these revenues do indeed rise or fall will also be substantially influenced by Congress, where a deal on a second relief package is still far from certain, although a bipartisan group is attempting to restart talks.

The Ed Fund’s contribution to the teachers’ pension system is also expected to spike to $38.9 million, up from $6.9 million this year, although this, too, could change. That accounts for about 3.5 cents of the expected rate jump.

In light of the unprecedented increase, the board of trustees for the teachers’ retirement system has instructed State Treasurer Beth Pearce to pitch to lawmakers and the governor a way to lower the sum.

Increasing school spending also plays a key role in the predicted tax hike, and, as in prior years, skyrocketing health insurance premiums are expected to be a key driver of rising costs. The tax letter predicts that education spending, overall, could rise by about $56 million, or 3.8%.

Much of the letter’s contents are prescribed by law, but it is still a deeply political document.

Some education officials bristled at language they thought pointed fingers at growing school spending in the face of continued declines in enrollment, but ignored state-mandated costs.

The letter made no mention that health care costs are now governed by a statewide contract, and are entirely out of local hands, said both Jeff Francis and Sue Ceglowski, who lead the professional associations representing the superintendents and school boards.

Districts do indeed have to contend with declining enrollment Francis said. But schools, which have had to transform themselves overnight to navigate the pandemic, cannot be asked to bear sole responsibility for a collective problem.

“Local school officials have a lot on their plate, and a wrong-minded approach, either from the administration or the General Assembly, would be to start to pick away at the K-12 system, when, as I indicated, there’s a lot here for everybody to work on together,” he said.