By Anne Wallace Allen/VTDigger

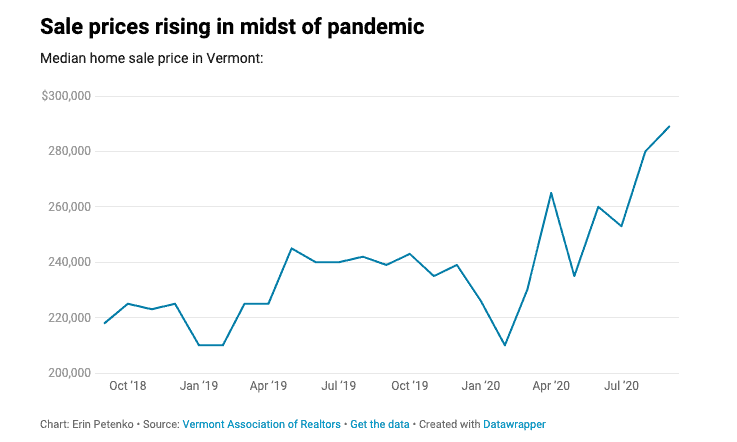

Home prices rose sharply this summer as out-of-staters moved into Vermont and market conditions deterred the construction of new houses, tightening the supply.

The median sales price paid in September hit $348,000 — 23% more than the median sales price of $281,335 in September 2019, the Vermont Association of Realtors said in its September market report, released Nov. 4.

Prices and sales volume started picking up in May and haven’t slowed, said Kathy Sweeten, who became director of the state real estate organization in August.

For the year to date, from January through September, home prices statewide are up 13% from the same period in 2019, according to the Vermont Association of Realtors. The year before, from September 2018 to September 2019, sale prices rose 7% year-over-year.

Heightened interest from out-of-state buyers, limited inventory, and low interest rates have all played a role, Sweeten said.

“People who had been looking over the wintertime got more active” in May, by which time they were competing with people who were seeking to get out of major metropolitan areas, Sweeten said.

The role of transplants

Anecdotal reports from real estate agents have pointed to an influx of out-of-staters this year.

Agents aren’t required to collect or report information about where sellers come from, but the Vermont Association of Realtors is working with the state Dept. of Taxes to obtain property transfer tax data to get that information. Sweeten said she doesn’t know when it will be available.

But what’s clear already is that Vermont is experiencing a larger real estate sales expansion than its immediate neighbors. In both New Hampshire and Maine, median sales prices rose 15% year-over-year in September for a single-family home, to $350,000 in New Hampshire and $270,000 in Maine, according to each state’s Realtor organization.

Vermont’s well-publicized success at controlling the rate of Covid-19 infection has been credited by many of the state’s housing leaders as a reason for the influx of new residents. While the populous Chittenden and Franklin counties typically see the most real estate activity, Sweeten said sales are up around the state. She said she couldn’t name a region of Vermont where prices haven’t risen.

Home price increases are a mixed blessing

While rising home prices are good news for people who want to sell their home and move elsewhere, local first-time buyers are experiencing sticker shock.

Policymakers, housing advocates and local residents say it’s getting more difficult to find housing in Vermont.

A lot of the recent surge in activity involves the high end of the market. Twice as many homes priced at $500,000 or more sold last year than the year before, said Maura Collins, executive director of the Vermont Housing Finance Agency, which provides financing to first-time homebuyers. Collins said her agency’s average borrower paid $167,000 for a home in 2018. The number of homes that sold for that price dropped 10% in 2019, Collins said.

“We’re seeing this big increase in the number of homes sold, but the real story is that it’s not all homes,” Collins said. “First-time homebuyers and people of modest means are really being left out of this market.”

Some of those people call Travis Poulin, director of Chittenden Community Action, for help if they’re considering a move to Vermont. If they don’t already have a housing plan, he advises them not to move.

“Even when you are the beneficiary of a housing subsidy, it can be difficult to find an apartment,” he said. “That is one of the largest challenges working with folks who are on fixed and limited income.”

Housing shortage isn’t new, isn’t unique

While Vermont’s a regional leader in rising home prices, it’s in no way alone in its shortage of housing stock. Many U.S. states have been struggling to incentivize home construction — not for the wealthy, but for working people — for decades.

The factors that keep the market from addressing the problem, in Vermont and the rest of the country, are complex and numerous. Many communities resist the kind of dense, multifamily housing that public policies incentivize and that could provide affordable homes for working people. In Vermont, land is also expensive, and zoning and other regulations often deter developers from building the dense housing that would make the project cost-effective. More recently, the price of building materials has risen sharply.

Until the pandemic began, creating more housing was a top priority for lawmakers, who were discussing a second housing bond to assist in the development of hundreds of units of housing.

The shortage isn’t good for the state, said Evan Langfeldt, CEO of O’Brien Brothers in South Burlington. He recently helped his parents move out of the 3,000-square-foot family home in Middlebury. He described the sale of that home as a “feeding frenzy,” and added that there are few options for his parents’ generation to move to when they want something smaller.

“The state has to be successful on a variety of fronts: bringing in more workforce, bringing in people planning to have kids, housing the existing boomers as they retire,” he said.

For companies trying to attract workers, the housing prices are a documented deterrent.

“It’s one of the reasons that we’re unable to retain a lot of young Vermonters living in the state,” said Erhard Mahnke, coordinator for the Vermont Affordable Housing Coalition. “Our housing is so expensive, and our wages are relatively low.”

Sweeten, of the Vermont Association of Realtors, said she expects the housing market to stay busier than in a typical year.

“It’s going to be interesting,” she said. “People can’t travel to Vermont without a quarantine, so it’s a big unknown for us what is going to happen. It all depends on inventory levels and the interest rates.”