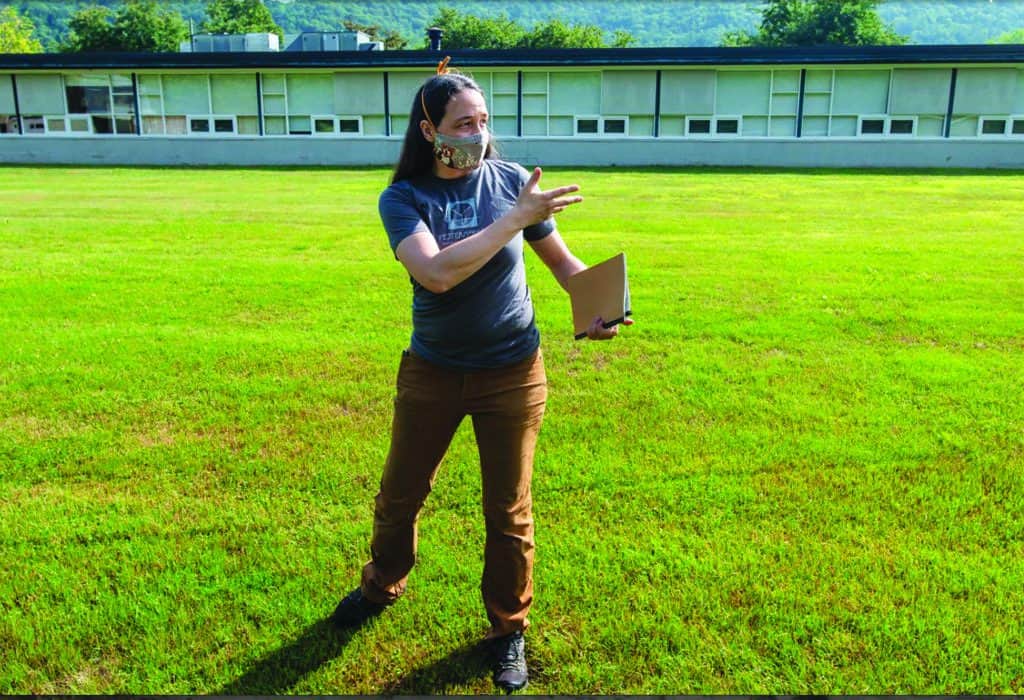

Lindley Brainard, a technology education teacher at the White River Valley Middle School in Bethel, explains the school’s plans to set up tents to teach returning students outside to mitigate possible infections from Covid-19.

By Lola Duffort/VTDigger

Before Covid-19 arrived in Vermont, middle school students in Bethel would start their days sitting in a circle in their advisory groups, with agenda projected on a screen.

Owen Bradley, the principal at the White River Valley School, believes students could start the day together again next school year. But this time, he thinks it’ll be around a campfire.

To reopen as safely as possible in the fall, Vermont’s pre-K through 12 schools are planning to implement a host of now universally familiar safety protocols — clear plastic shields in high-traffic areas, temperature checks, masks. But with transmission of the virus apparently significantly reduced outside, some teachers and administrators are considering turning to an already popular practice in many schools: education outdoors.

Vermont has a long tradition of using the state’s plentiful forests, meadows, and rivers as alfresco lecture halls and science labs. About 60 schools in the state already implement some kind of nature-based immersion program on a weekly basis, according to Amy Butler, the director of education at the North Branch Nature Center in Montpelier.

North Branch operates ECO, a program that gets elementary students across central Vermont outside, once a week, for nature-based lessons that align with the state’s science curriculum standards. ECO is part of Inside-Outside, a regional network of New England educators that teach in nature immersion programs, and the group recently published a position paper encouraging schools to incorporate outdoor education as part of their pandemic mitigation strategies.

“Allowing children to have more time outdoors when school does open seems like a really, really safe and healthy idea, not only to curb the transmission of the virus – but also just for social, emotional, mental health,” Butler said.

At White River Valley, Bradley said the school is planning to hold in-person instruction outside most of the day, every day, until at least Thanksgiving break.

Like many Green Mountain State educators, the administrator has a history with outdoor education, and taught in several such programs in Montpelier and Twinfield. The Bethel Middle School abuts a forest, much of it publicly owned, and its students have trudged into the woods on a weekly basis for years. Four faculty members already have formal training in outdoor education.

“It’s so ingrained and part of the Vermont experience,” he said.

He notes that even in pre-pandemic times, students have gone outside throughout the winter, and he’d like to see classrooms stay mostly outdoors for the duration of the academic year. Still, he freely acknowledges plenty of details have yet to be ironed out.

“We have a lot to figure out before then,” he said.

As in many Vermont schools, White River Valley Middle will be creating “pods” of students who will be assigned the same teacher and stay together, isolated from their peers, to further mitigate the risk of transmission. Each pod will be assigned a shelter space they can go to – like one of the town’s churches – so they can gather indoors in large, open spaces in case of inclement weather.

Bradley thinks more outdoor learning can help the school better lean in to teaching practices it’s been shifting toward anyway – more project-based learning, for example, and social-emotional development. But for those subjects that don’t so easily translate to a forest setting – like, say, algebra – instruction may simply take place online, and the district is already planning to have at least one remote day a week. Particularly frigid days might also be treated like the snow days, with kids also expected to learn from home.

Outdoor education will likely be most easily adopted – or expanded upon – in small, rural schools that have easily accessible natural areas. But even in urban areas, some educators are thinking about taking the classroom outside.

In South Burlington, high school principal Patrick Burke said the school would like to see teachers and students head outside as much as possible in the fall, and is already working on beefing up its wifi to make sure it’s accessible everywhere on campus. He’s asked the district’s facilities director to contact vendors about what might be available for weather-proof outdoor learning spaces.

Administrators were recently wrestling with the problem of adequately cleaning every desk and chair in the 1,000-student school between each use with only two custodians on staff. So Burke suggested a bold idea – why not just remove most of the furniture altogether?

Instead, every student might be issued their own individual folding camping chairs to tote around between classes, including when they head outside.

“When it comes to doing logistical things that can get our students on campus, nothing’s off the table,” he said. “I don’t think it’s a time for people to enter into conversations like this by identifying all of the reasons that we can’t do it.”

David Schilling, the principal at the pre-K-12 Danville School, came to public schools after a little over a decade in environmental education. Unsurprisingly, he’s bullish on learning outdoors.

“When we look at what we’re trying to cover with our science standards, when we look at what we’re trying to teach with community building and social emotional skills – a lot of that can be done outside,” he said.

In the short-term, the Danville School is trying to secure tents so that groups of students can gather outside in the fall. The state’s guidance about how to reopen schools safely instructs schools to close indoor, communal spaces, including gyms, and Schilling thinks physical education classes, at a minimum, could be held outdoors. In the long-term, the school and community volunteers are already at work cleaning up a small nature trail on its property that elementary students could use for nature-based play and learning.

Still, Schilling says plenty of instruction will need to happen inside the four walls of a classroom.

“When I think about a comfortable environment for math instruction, for writing, for reading – there needs to be an indoor component, even when it’s not cold,” he said. “We have bugs, we have sticks, we have distractions.”

He’d like to see some learning take place outside come winter, but he thinks that’s something faculty still have to work up to. The school would also have to secure adequate winter clothing for students who don’t have it. And that’s only one of many logistical problems the school would have to work out.

“I certainly don’t see, like, groups outside under tents in the winter. That seems pretty miserable to me,” he said.