Demonstrators call for an end to systemic racism in Rutland and beyond

By Aliya Schneider

Protestors were met with honking, cheering, and gestures of support as they protested along Main Street in Rutland on Sunday, June 7.

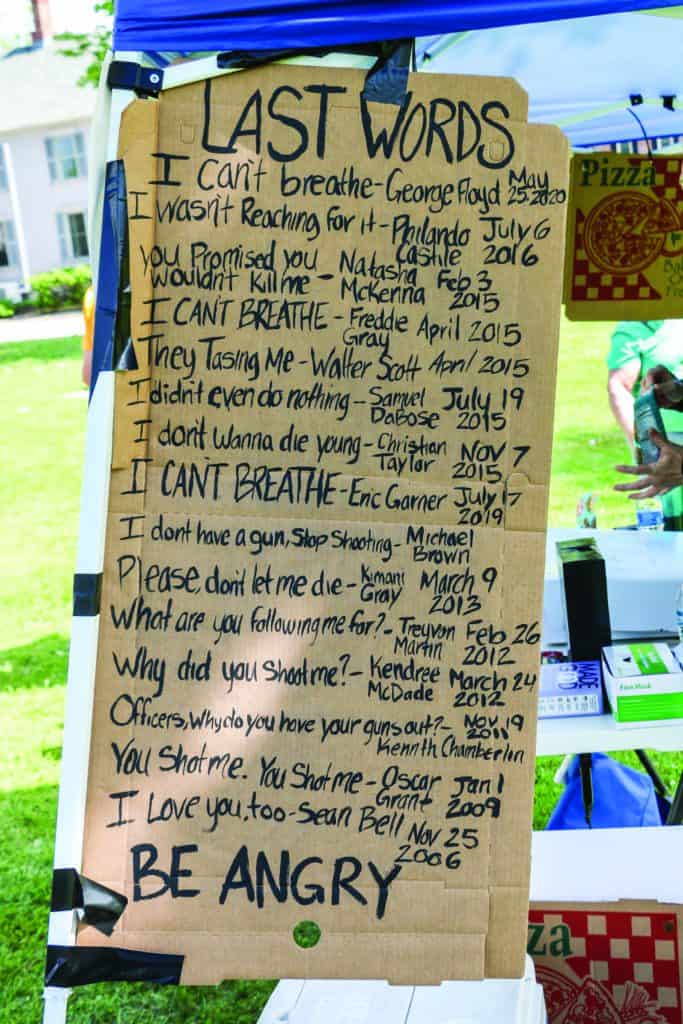

“Black lives matter!”; “No Justice! No Peace!”; “Say his name. George Floyd” and “Say her name. Breonna Taylor” crowds chanted and signs read.

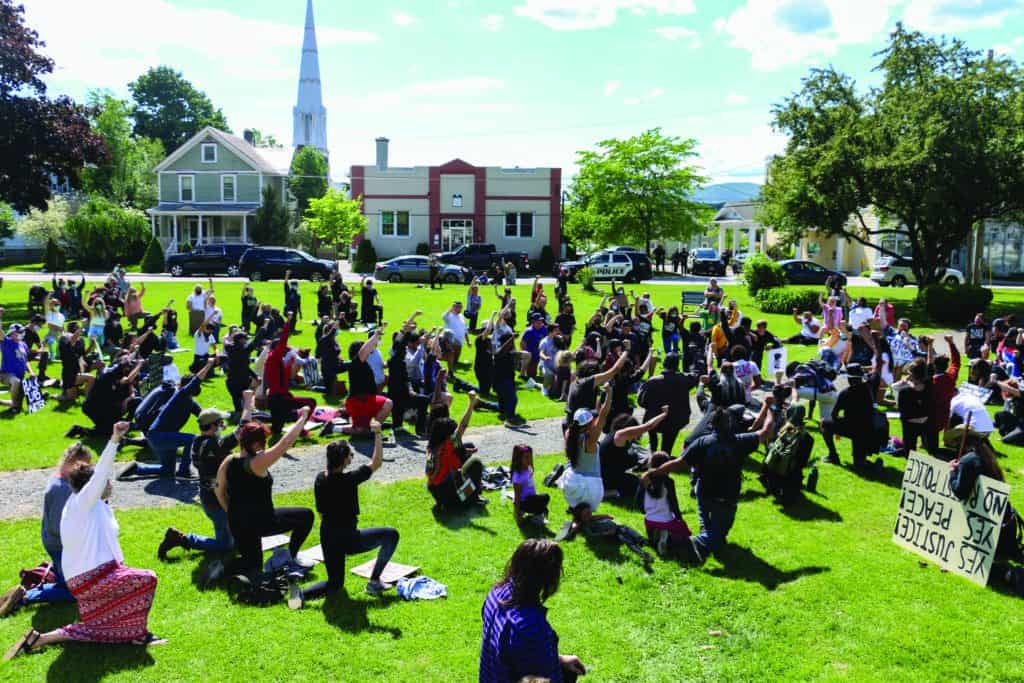

Rutland police officers estimated that between 500 and 1,000 participants attended the Black Lives Matter protest in Main Street Park, with people coming and going throughout the day.

Aris Sherwood, Kjersti Conway, and Maddy Thorner organized an event from 10 a.m.-2 p.m. with the help of the Rutland NAACP, and Taylor Torres organized a march that followed, bringing protestors along Woodstock Avenue to Rutland High School, where the crowd paused their chanting to sing “Amazing Grace” before returning to the park.

After the march, protestors kneeled for the second moment of silence of the event — lasting 8 minutes and 46 seconds, the amount of time former officer Derek Chauvin held his knee on George Floyd’s neck, resulting in Floyd’s death as three other officers watched in Minneapolis last month.

The protest lasted until 3:45 p.m.

“With protests not just throughout the country but throughout the world, we thought this movement was something that Rutland needed,” Sherwood said. “This was the perfect opportunity to call out the schools, and the police station, and the hospital, and tell them to do something about the racism [in] our own communities. We also wanted to make sure that every black person in our community knows they are seen and we support them, and that their lives matter,” she added.

Torres set up a booth in the park with her boyfriend, Kevin Alomar, and

friend Sarah Johnson, where they sold Black Lives Matter t-shirts that they printed themselves to raise money for the movement. They sold out within the first hour of the event, raising $572. They also handed out free water, masks, and popsicles.

At one point, a group of drummers and African dancers performed for those in the park, while others continued chanting along the street.

Some carried signs that called for the defunding of the police, a conversation that has gained traction in response to documentations of police brutality, and some hugged and thanked Rutland police officers working at the protest. Officers were present all day and guided protestors along the march route.

Jack Crowther and Sue Crowther held signs on the side of Main Street that said “Justice for George.” “We’ve been here 50 years and I don’t remember seeing anything like this. This size, this intensity—it’s impressive,” Jack Crowther said.

Tabitha Moore, the president of the Rutland NAACP spoke at the beginning of the event. She praised the organizers’ efforts and emphasized that “young people are stepping in to lead and we need to follow and support them.” She added, “a lot of white Vermonters think this couldn’t, and doesn’t happen here—that we are immune from acts so atrocious as police brutality and white supremacy. So you know, we’re not.” She referenced local, and recent, incidents of racial profiling and harassment, as well as difficulties in encouraging anti-racism in local government, schooling, and policing.

“The NAACP is the nation’s oldest and largest civil rights organization. We have been around 111 years and guess what? Our message hasn’t changed. We’re saying the same thing we said then,” she said.

“‘But look what we already do, why focus on what doesn’t work?’ we hear. And to that I say, because what you’re doing is not enough. And because what you aren’t doing is killing us just the same. We die from heart attacks and mental health issues, suicide and other diseases. Systemic racism kills us. It just isn’t as quick as a bullet to the body while you’re sleeping in your bed,” she said, referencing Breonna Taylor, a then 26-year-old EMT who was fatally shot in March by police officers in her home, who entered while she was sleeping in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

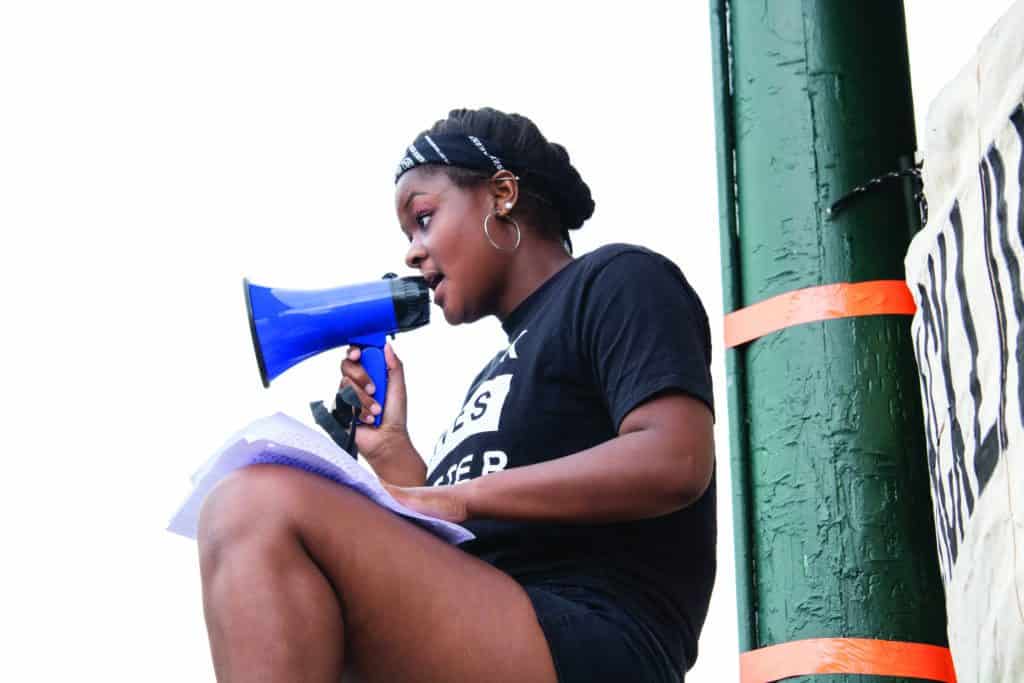

College student Domonique Thorne and high school students Makieyah Hendrickson and Ella Norton were also scheduled to speak.

Thorne spoke about his experiences with racism, and told the Mountain Times that if young people are taught about history accurately, “then maybe one day racism won’t be as bad as a problem as it is today.”

In Norton’s speech, she said her peers at Rutland High School use the n-word often, and casually, not recognizing the weight it holds. She said that when she is outspoken about her opinion, she is “labeled as having a bad attitude,” and when she is upset, she is labeled as a “mad black woman instead of a mad person.”

“If you are not black, then you really truly do not understand the frustration we deal with on a daily basis,” she said. “I am tired of seeing so many people being shot just because of their skin color. I am so tired of my people fighting, and fighting, and fighting, for just some respect and still not receiving it. And most of all, I am so tired of the ignorant racism that goes on every day, even in this town,” Norton said to the crowd.

Makieyah Hendrickson, also a Rutland High School student, recalled a time her friend told her that her skin looks like “dog poop.” “This relates to the videos I have seen of black children bawling their eyes out because they think they aren’t good enough. They think their skin is too dark and their hair is too nappy and ugly because it doesn’t fit society’s standards,” Hendrickson said. She shared that she had a close friend who posted a photo caption on social media that said, “I pick strawberries like [n-words] pick cotton.” “Ever since that post, those words have never left my head,” Hendrickson said to the crowd. Along with speaking about racist remarks from her peers, she spoke about being watched by store clerks to make sure she isn’t stealing, an experience she shares with other speakers from the day.

“Imagine every time you step out your door there is a target on your back. This is what it’s like for black people in America,” she said. She listed off the different activities black people have been shot doing in the United States, including, running, buying Skittles, and sleeping in their home, referencing Ahmaud Arbery, Trayvon Martin, and Breonna Taylor.

“The list goes on and on,” she said.

When Sherwood offered the megaphone for those who didn’t have speeches prepared, a woman named Nikki Stone volunteered to speak. “I was born and raised in Rutland Vermont,” she said, and the crowd cheered. “We say ‘woo’ now, but back in the 70s and 80s it wasn’t ‘woo,’” she added. She spoke about her experiences with racism in Rutland, including being chased and called the n-word.

“I didn’t stand up for my people. I didn’t stand up, because I didn’t know how. I was raised in an all-white society, as the only black kid in the school… And it’s only today, 45 years old, that I’m actually taking a stance, right now, for my people—for black people, for brown people, for any minority that is being treated less than.”

She said that while there are more black people in Rutland than when she was growing up, she still worries for her children.

“You guys, we’re gonna make a difference. I’ve come out of the ashes of what I thought would be a life that went nowhere. And I now have a great career… and I know that each and every one of these young black youth can do the same thing,” she said.

Terrohn Richardson spoke about the unequal treatment within the criminal justice system in Rutland and in the whole country. “I feel as though a lot of people see me as a drug dealer, like I’m not from here because of the color of my skin. It’s something that is unfortunate, but it’s something that is changing,” he told the Mountain Times. Richardson said that black men arrested for drug involvement are typically seen as “a dealer” or “a predator,” while a white man arrested for the same charge is seen as “sick” and in need of help.

“This is my community and it doesn’t feel good to walk outside and feel separate from it,” he said. When he visits family in Newark, New Jersey, where the black population is significantly higher than in Vermont, he said he isn’t viewed the same way as he is in Rutland. “I can actually live and be me and not have eyes on me thinking that I’m out doing something less than favorable… I’m able to go out and just be, without having to turn the other cheek to some intolerances that I personally face on an everyday basis,” he said to the Mountain Times.

“It’s not just black, this is all of our fight,” Richardson said when speaking to the crowd, and was met with cheers. “If you don’t like what this crowd looks like, then you should probably live elsewhere, because this is what it’s all about.” Cheering continued supporting each speaker, validating their experience.