By Michelle Monroe

Vermont’s education tax system is notoriously complex. When reviewing the school budgets presented prior to Town Meeting Day, here are some things to keep in mind.

All education taxes go into the Education Fund. Since the Brigham decision and the passage of Act 60, Vermont has paid for its schools as a state. No community pays for just its school. However, the Legislature chose to let communities continue to set their school budget, tying each district’s tax rate to its per-pupil spending to discourage excessive spending.

Most communities in Rutland and Windsor counties now receive more money from the Education Fund than they pay in education property taxes.

The tax rate only applies to households earning more than $141,000. With Act 68, Vermont made education property taxes income-sensitive. There is a cap, which varies based on per pupil spending in each district, on how much income a household earning less than $141,000 may pay in education taxes. If their tax bill exceeds the cap, a credit is applied to their bill.

Tax rates are likely to be less than school districts anticipated. One of the most important parts of the tax rate formula is the yield. The yield is how much schools would be able to spend if the homestead tax rate was $1. Each year, the Dept. of Taxes must announce a yield by the end of November. Schools use that number when budgeting.

The yield is based on how much money is in the Education Fund (in addition to the property tax, it is also funded by lottery revenues, a portion of the sales, rooms and meals taxes, and a transfer from the general fund) and how much the Dept. of Taxes believes schools will be spending.

When the department announced the expected yield in November, school spending across the state was expected to increase by 3 percent. As school budgets have come in, the spending increase across the state is closer to 1 percent. As a result, the final yield set by the legislature will likely be higher than the department projected in the fall.

If the yield goes up, homestead tax rates will fall.

The non-homestead property rate for business properties and second homes is set by the state. It is then adjusted based on the Common Level of Appraisal in each community, but the local school budget itself doesn’t directly impact the non-homestead tax rate.

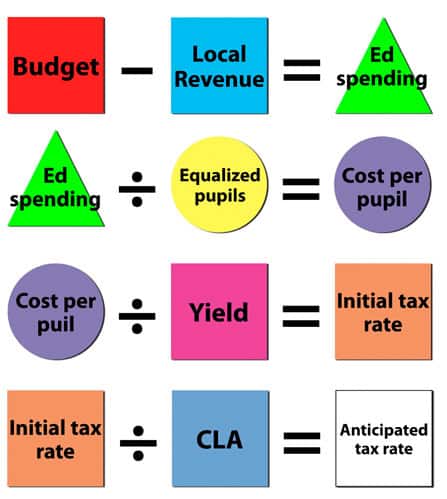

Total budget: The districts full, proposed budget for the upcoming school year.

Local revenues: Grants, tuition, and other non-Education Fund sources.

Education spending: This is how much money the school will need from the Education Fund to operate.

Equalized pupil count: The state weights them so that students whose education costs more also count more. Students with special needs are also weighed more heavily.

Cost per equalized pupil: How much each school spends per pupil from the Education Fund.

Yield: This is how much cost the Education Fund could support per pupil if the tax rate paid by all homeowners was set at $1. This varies each year.

Initial tax rate: The difference between the yield and the districts per pupil spending. If the school spends more than 25 percent more than the yield, then its initial tax rate will be $1.25.

Common Level of Appraisal (CLA): This percentage is used to adjust the tax rate so that homeowners whose appraised home values are higher than the market rate don’t pay more taxes than they should. Conversely, it also raises the tax rate for homeowners whose appraisal is lower than the market rate. A decline in the CLA will raise a town’s tax rate in comparison to last year. An increase will lower it.

Anticipated tax rate: This is the tax rate homeowners earning more than $140,000 per year can expect to pay if the school’s budget is approved. The final tax rate will not be known until the final yield is set by the Legislature after Town Meeting Day.