By Julia Purdy

After the Gospel, Charles Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol” is probably the best known story of Christmas in the English language. Since 1900, the entertainment industry alone has produced at least 50 versions for film and TV. We enjoy the “Carol” for its feel-good message and cornucopia of special effects, as Dickens himself intended. The visual variety keeps us interested, the ghosts are not too scary, and the festive holiday spirit makes grinding poverty easy to overlook.

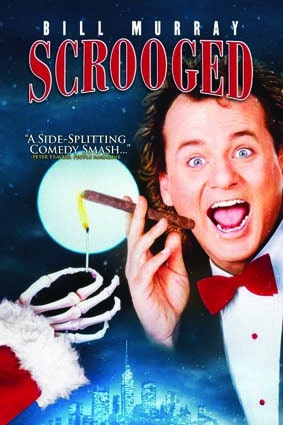

One rendition of this classic story is the 1988 movie “Scrooged,” which was recently featured at the Paramount Theatre’s free movie night, Dec. 13. The movie stars Bill Murray, in a performance acclaimed as one of his best. Murray’s wackiness depends on his persona as the lovable class clown we all remember from school days, but like all great actors he can be taken on many levels.

“Scrooged” is not only riveting to watch, but it echoes Dickens’ own message of redemption, suggesting that while we may not be able to undo the past but we can help to heal it and chart a better course.

Murray plays Frank Cross, a loner and hard-driving president of a television network who lets no one get in his way, who calls himself “a widow to broadcasting” and whose entire goal is to maximize ratings and advertising revenue. The path to that goal is to introduce gratuitous violence into every production, including Christmas programming.

The studio is now preparing to broadcast a live Christmas Eve production of “A Christmas Carol” in the traditional format, complete with John Houseman delivering the introduction, but Cross livens it up with scantily clad female dancers. Cross’s “Christmas Carol” spot features a terrorist attack, drug addiction and road rage—his idea of a great promo. When an elderly woman dies from fright watching it and the incident makes the headlines, Cross shouts, “You can’t buy publicity like this!!”

Even though the promo makes his whole production committee sick, Elliot Loudermilk (Bobcat Goldthwaite) is the only one to voice an objection and is fired on the spot for his trouble, in spite of the fact that it is Christmas Eve. Loudermilk, a mild-mannered, bespectacled little man with a reedy, high voice, loses his wife and turns to booze and living on the street.

Like Dickens’ tale, the action takes place entirely on the night before Christmas. The parallels with Dickens’ story are there but not overbearing.

In another part, Cross’s assistant, Grace Cooley (Alfre Woodard), needs to leave work early on Christmas Eve to take her son Calvin to the doctor. We learn that her 5-year-old son has never spoken, as a result of seeing his father killed. But Cross tells her she must stay and work sand charms her into canceling the appointment.

Calvin is the Tiny Tim figure. He pays close attention to a production of “A Christmas Carol” on TV when Tiny Tim utters the famous words, “God bless us, every one.”

On the set of Cross’s production, Cross sneers at a staffer who gets seriously injured and showers verbal abuse on just about everyone. Nevertheless, he insists on being addressed as “Mr. Cross.” He debates whether to send a towel with the company monogram to everyone on his list.

Out on the street in Manhattan, he brushes past a band of musicians playing for money, and pushes an elderly woman aside just as she is about to enter a cab. He attends an event where he receives a humanitarian award and in his speech he says how “I wanted to give” and that he will cherish the statuette (after flicking it to see if it’s solid metal—it isn’t), then leaves it behind in the taxi.

When Cross is back, alone in his suite, he makes himself a drink. Then the door blows open and Marley’s ghost appears. This time it’s his old boss Lew Hayward (John Forsyth), a walking mummy dressed for the golf links, who warns him to mend his ways. He says he was a “captain of industry … feared by men and adored by women,” but “mankind should have been my business, charity, mercy, kindness, that should have been my business.”

Hayward tells Cross of the three visitors he will receive.

While Hayward is talking, a golf ball is pushed out of a hole in his skull by a mouse, who goes back inside. When Cross tries to argue with the ghost, the ghost pushes him through the glass window of the skyscraper and he dangles, screaming, above the street far below. When he tries to hold onto the ghost’s hand, it breaks off and Cross plunges down, only to collapse into his recliner. It was all a dream.

Like Dickens’ Scrooge, Cross puts on a tough act but his fears begin to take hold. At noon the next day, at lunch with associates, Cross hallucinates an eyeball in his highball, and he is the only one who sees a waiter who catches fire from a Baked Alaska (fiery ice cream cake). He rushes out and gets into a cab, which he finds to his horror is driven by the Ghost of Christmas Past. The ghost takes him on a wild ride through the streets as the meter clicks backwards to the year 1955.

They arrive at Cross’s childhood home. The 4-year-old Frankie is watching a Christmas program on TV with his worn-out mother, who is absorbed in a crossword puzzle. The father, evidently a butcher, arrives and throws a package of meat on the floor in front of Frankie. Frankie asks if it’s the choo-choo he asked Santa for, and the father sneers that he’ll have to earn the money for a choo-choo: “All day long, I listen to people give me excuses why they can’t work … ‘My back hurts,’ ‘my legs ache,’ ‘I’m only four!’ The sooner he learns life isn’t handed to him on a silver platter, the better!”

The ghost-cabbie is looking on as tears begin to run down Cross’s face. It comes out that Cross’s childhood was lived vicariously through early TV serials like “Little Home on the Prairie” that celebrate family togetherness and loving parents.

They next travel to 1968 and stop in at an office Christmas party where a staffer is passing around a photocopy of her buttocks. Cross is a long-haired hipster in bell-bottoms, who lives a self-consciously soulful life, eschewing tawdry hijinks and Chinese food. He meets Claire, a counterculture girl who is attracted to his awkward charm, but over time as show biz starts taking precedence, she realizes that money is more important to him and reluctantly breaks up with him.

Here the movie inserts the scene from an old film of “A Christmas Carol” in which Ebenezer Scrooge’s fiancee breaks the engagement, observing how he has changed from the loving man he once was to a money-grubber who thinks only of profit and loss. Claire goes on to become the executive director of a homeless shelter. … but she never quite gives up on Cross.

The Ghost of Christmas Present (Carol Kane) is a charming, nutty fairy with a wand, who, like Dickens’ ghost, takes him around to see how normal people are celebrating the season. They stop by Grace’s home where her kids have decorated Calvin with tinsel and shiny glass balls, to substitute for the Christmas tree they cannot afford. They visit the home of Cross’s brother James in a scene that closely parallels Scrooge’s visit to his irrepressibly cheerful and all-forgiving nephew. Cross is finally moved, as the fairy said he would be.

But although the fairy ghost takes a childlike delight in the season’s pleasures, she is also all about tough love (“Sometimes the truth is painful”). There is much cuffing and whacking and a physical confrontation involving a toaster, which knocks Cross out of the scene and into a dank, tomb-like space under a sidewalk with dirty icicles dripping down and people walking overhead. He says, “Well, this is nice. Where are we, Trump Tower?” (The audience picked up on that one, chuckling and making comments to each other.)

Finally back in his office, this time the door blows open and it is Elliot Loudermilk, brandishing a shotgun. In possibly the funniest sequence in the whole film, Loudermilk chases Cross around the building, blasting away, until Cross finally ends up in an elevator with … the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come.

Dickens made his appeals to help the needy by warning of raising a future generation that is at risk. The final ghost is a fearsome monster that may give young children seeing “Scrooged” nightmares. It takes Cross to a prison or a mental hospital where a teenaged Calvin is being held in a padded cell. Next, three hungry kids appear outside a swank coffee shop where Claire—now a society lady in heavy makeup and a big hat—is having tea with friends. The friends point to the children and Claire simply shrugs and comments, “I’ve wasted 20 years of my life on pathetic little creatures like those. Finally a friend of mine said to me, thank God, ‘scrape them off, Claire. If you want to save somebody, save yourself.’”

Of course, that friend was Cross. In keeping with Scrooge’s visit to his own grave marker, the sequence culminates in a scene where Cross experiences his own horrifying cremation, in a ceremony attended only by a priest, James and a secretary from his company.

Back in the office, Cross undergoes his transformation. He grabs the unbelieving Loudermilk, hugs and kisses him, and shouts: “Francis Xavier Cross! That’s me! But the funny thing is, that’s not me! … I was a schmuck. But now I’m not … ”

The scene switches back to the production of the Dickens story. Scrooge (Buddy Hackett) flings open his windows on Christmas morning and hails the boy below to go and buy “the biggest goose …” At the same moment, Cross bursts onto the set before the astonished eyes of everyone. He makes his confession before the world and before Claire, who is watching the TV at the homeless shelter. “It’s Christmas Eve,” he says to her through the camera. “It’s not too late.” She rushes to the studio. At the same time, Calvin appears, who has been brought to the studio to watch the production. He tugs at Cross’s jacket and finally speaks, repeating Tiny Tim’s words.

Cross’s message to the world is admittedly a tear-jerker but perennially relevant. “For a couple of hours out of the whole year, we are the people we always hoped we would be. It’s a miracle. … You do have to get involved. There are people who are having trouble making their miracle happen. There are people who don’t have enough to eat, people who are cold, you can go out and say hello to these people, you can take an old blanket out of the closet, you can make them a sandwich and say, ‘By the way, here!’ … You won’t be one of these bastards who says, ‘Christmas is once a year and it’s a fraud.’ It’s not! It can happen every day!”

Charles Dickens grew up in dire poverty. As a journalist he became a lifelong critic of Adam Smith’s laissez-faire economics and philosophy, which still underlies modern conservative economic theory.

In 1776, Smith’s “The Wealth of Nations” laid the foundations of laissez-faire economics, which is not so much a policy as the absence of one. Smith—never a sentimentalist—held that the law of supply and demand (today’s “market forces”) is tantamount to a law of nature, above and beyond human influence. Governmental regulations or protections are viewed as not only unnecessary and futile but undesirable. In Adam Smith’s view, the demands of “the economy” trump everyday human needs and priorities. Then “Social Darwinism” explained away the shortcomings and failures of society’s “losers” as their own fault; the causes of poverty were put down to “idleness” or overpopulation or both.

When both Scrooge and Frank Cross have both been forced to recognize that the way they were, wasn’t working for them, they were fortunate to land in a safety net made of the goodwill of others, even those they hurt. Casting off a cemented, bad reputation takes courage. They could only pull it off by admitting to their faults, rediscovering their “inner child,” and abandoning the motivation to belittle and exploit others. They feel the ecstasy of having a great weight lifted off.

Interestingly enough, neither Scrooge nor Frank Cross apologize in so many words. Perhaps Dickens believed that actions speak louder than words, after all.